The state’s HSN is operating at an estimated $250 million deficit for fiscal 2025, dumping the burden of payment directly onto the state’s health centers and hospitals.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

When an under or uninsured Massachusetts resident requires certain medical treatments, such as many in radiology, psychiatry, or rehabilitation, the cost of their care often falls to the state’s Health Safety Net. The fund serves to reimburse community health centers and acute care hospitals for specific essential services for those under and uninsured, including for those whose services aren’t covered by Medicaid.

But what happens when that funding falls short?

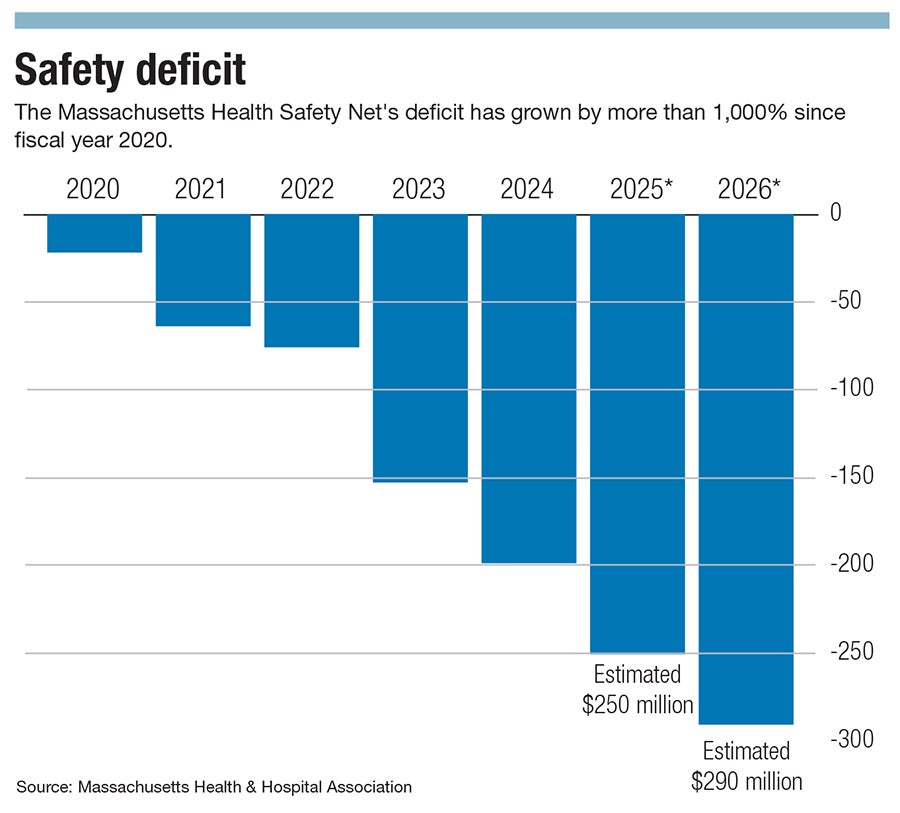

The state’s HSN is operating at an estimated $250 million deficit for fiscal 2025, dumping the burden of payment directly onto the state’s health centers and hospitals. That’s a deficit increase of more than 1,000% since fiscal 2020, and the shortfall is expected to reach approximately $290 million in fiscal 2026, according to the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association.

In Central Massachusetts, healthcare leaders are warning the shortfall will mean exacerbated emergency wait times, restricted service offerings, and potential hospital closures — consequences expected to touch everyone in the region, uninsured or not.

“That's a disaster for our patients. That's a disaster for us as a health center, and that's a disaster for the city of Worcester,” said Louis Brady, president and CEO of the Family Health Center of Worcester.

Struggling ERs

Established in 2006, HSN was created to help bridge the payment gap for health centers and acute care hospitals providing care to some of the state’s most vulnerable residents. This fiscal year, hospitals and insurers each contributed $165 million while the state kicked in an extra $15 million, according to the MHA.

The rise in the HSN deficit is a cumulative result of systemic issues intensified since the COVID pandemic, namely, the healthcare workforce shortage.

“It's really an industry that is struggling. They're so good at responding, doing what they need to do to care for patients. But it's really a workforce still recovering from COVID, and a system that just isn't functioning anymore the way that it used to,” said Steve Walsh, MHA president and CEO.

Throughout the eight emergency departments within UMass Memorial Health, based in Worcester, wait times averages range between 27 to 181 minutes. The system’s stand-alone emergency facility in Webster has the shortest wait times while its trauma center in Worcester has the longest.

Longer wait times come at the financial expense of hospitals because they’re simply not able to treat as many patients, said Walsh.

Massachusetts has been historically known for its high numbers of insured patients, with 93.8% of residents reporting continuous health insurance coverage, according to data collected by the state Center for Health Information and Analysis.

Still, hospitals are seeing more patients, and more of them are coming in without insurance, said Walsh.

Hospital occupancy rates in the U.S. have increased from an average of 63.9% between 2009 and 2019 to an average of 75.3% between May 2023 and April 2024, according to the healthcare publication Healthcare Dive.

Difficult decisions

UMass Memorial Health in Worcester expected to receive about $22 million more from the HSN than it did this year, with the system losing about $40 million more due to costs not covered by the safety net, said Dr. Eric Dickson, president and CEO of UMass Memorial.

The system has already attempted to use insurers more to help support the deficit, but that’s not enough.

“If you're losing money overall, you tend to try to grow profitable programs and shrink unprofitable programs,” said Dickson.

The least profitable programs at UMass Memorial are pediatrics, obstetrics, psychiatry, and primary care: services that can ironically reduce the cost of care for the state.

“But if you shrink pediatrics, OB, primary care, and psychiatry, where do you think those patients end up? The emergency department,” Dickson said.

And the emergency room is the most expensive place in the hospital to deliver care. Due to its nature, providers in the ER are usually beginning care without information on their patients, meaning more time is spent with each client, further stalling wait times.

Emergency room patients in Massachusetts experience the third-longest wait times in the nation, according to a report by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“If we don't figure out how to fund this shortfall, and we subsequently see a deterioration in those key programs that keep people out of the emergency department, we are going to be number one, and that's embarrassing for the state of Massachusetts,” said Dickson.

UMass has already had to make difficult decisions to cut programming. In the last nine months, the system has closed two primary care clinics and one teen detox center within its behavioral health affiliate due to financial strains, in part associated with the Health Safety Net shortfall.

Far-reaching impacts

“When HSN is a shrinking platform, it's a shrinking raft. Then [patients] have fewer options, fewer access to services outside of our health center, and the broader ecosystem that then impacts their health and exacerbates the disparities,” said Brady.

When the region’s hospitals face a deficit in funding, that hurts the health centers too, he said. Community health centers care for patients regardless of their ability to pay, and emergency rooms legally cannot deny patients because of lack of insurance or financial means.

Brady said the financial strain on hospitals and their potential service reductions is going to directly impact the health center’s patients as residents scramble to find care, with those already facing disparities impacted the most.

People who live in Worcester’s Salisbury Street neighborhood have a life expectancy of 84 years old, said Brady, an expectancy 12 years higher than those two miles down the road, who live in Union Hill, where the life expectancy is 71.6 years.

“That's something that we can tackle. We know the ways to do that, and we've got a plan to take that on. Spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak,” he said.

But regardless of zip code, the HSN’s shortfall will reach all residents, in part due to hospital closures, said Dickson.

In August, Central Massachusetts lost Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer. The hospital was run by the for-profit, Dallas-based Steward Health Care, and its closure immediately resulted in an increase in neighboring emergency department patients in September, according to data collected by The Boston Globe.

“We had 10 [Massachusetts] hospitals bankrupt in 2024. Two of them came out. Six of them were acquired, and two of them are still closed,” said Dickson. “If we don't figure this out, then there will be more.”

In navigating the HSN shortfall, FHCW’s strategic plan has heavily leaned into collaboration with neighboring organizations in order to help meet the needs of its patients. The center may need to consider borrowing money, going into lines of credit, and paying interest on that debt.

While that can provide some relief, it’s at the expense of forward momentum, such as stalling the hiring of another staff member working toward the center’s mission or adding a nurse or community health worker to its care team, Brady said. All decisions set off chain reactions throughout the region.

“That squeezes that vital resource that should be available to everyone in the community, and makes it harder for everyone in the community to access it,” said Brady. “So, even though you are insured, this is your fight.”

Mica Kanner-Mascolo is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the healthcare and diversity, equity, and inclusion industries.