With a pandemic affecting those clients who may be more susceptible to coronavirus and everyone else, community health centers – like their acute-care hospital siblings – have been thrown into disarray.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

On a good day, community health centers work with a population less likely to have health insurance and more likely to have underlying health issues, language barriers or other challenges.

With a pandemic affecting those clients who may be more susceptible to coronavirus and everyone else, community health centers – like their acute-care hospital siblings – have been thrown into disarray.

Regular check-ups have been postponed indefinitely or pushed online, a potentially major challenge with a patient community less likely to have the technology at home to log on to tele-health appointments. A welcoming environment has necessarily been shut off to keep coronavirus risks away from other patients and workers. And a lack of regular appointments for primary care, optometry, prenatal care and other needs means these centers aren't seeing the revenue to survive long-term.

“We had a big open front door that was very welcoming to walk-ins,” said Noreen Johnson Smith, the vice president of development and advancement at the Family Health Center in Worcester. Even with workers wearing personal protective equipment, operations at the facility have been upturned.

“We have an obligation to our caregivers to keep them safe while they're at work,” she said.

The state’s 38 such community health centers care for 1 million people, the largest primary care system in Massachusetts, said James Hunt, the president of the Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers.

“It’s a sea change from the normal course of business,” Hunt said of how centers have dramatically shifted care so quickly. “The role of the community health center could not be more important.”

Shifting care

Federally qualified community health centers such as the Family Health Center and the Edward M. Kennedy Community Health Center in Worcester are typically seen as the first and sometimes only place marginalized people in the community turn for health care. The population tends to be lower-income, with many who struggle with substance abuse and homelessness.

While that population's needs remain, such centers now have to make as drastic of an adjustment as Saint Vincent Hospital, UMass Memorial Health Care and other Central Massachusetts hospitals who have shifted around intensive care beds, delayed many appointments and banned nearly all visitors in an attempt to best respond to the pandemic.

“A lot has changed for everyone in the world, and I think we’re no different,” said Stephen Kerrigan, the president and CEO of the Kennedy Community Health Center. “We’re set up well to meet the moment that we’re in.”

Both Kennedy and the Family Health Center have taken on less-severe coronavirus cases, where they can evaluate and monitor patients who self-quarantine at home. That’s kept some strain off Saint Vincent and UMass Memorial, which have been augmented by more than 200 beds at a field hospital at the DCU Center in Worcester for COVID-19 patients who don’t need to be in intensive care.

At Kennedy, which has centers in Worcester, Framingham and Milford, the entire behavioral health operation is taking place online, as is much of primary care. Much of the dental staff has been repurposed for support in the pharmacy center, particularly for helping to control a large number of people waiting for prescriptions who need to be physically spread apart, including in what's normally the behavioral health waiting area.

Most of its school-based health centers have been closed while school is out of session except for where schools have remained open as temporary homeless shelters. Kennedy is working on securing blood pressure cuffs it can give to patients at home for checking their own signs, along with having providers check in with them online or by phone.

“We’re working through a lot of creative measures to provide more health care to people in their homes than we were before,” Kerrigan said.

Both Worcester community health centers have had screening tents set up to help potential coronavirus patients without possibly infecting people inside a waiting room. Both have required their staffs to wear face masks and other protective gear throughout their shift.

The Family Health Center, which also has a facility in Southbridge, has directed its staff to enter through a back door when starting their shift, where they have their temperatures taken.

At the Family Health Center, primary care, behavioral health and other areas have gone online – and even some tele-dentistry as a way to keep up with patients who don't need emergency work. The center has launched home delivery pharmacy services and its leadership has worked with the city administration, UMass Memorial and Saint Vincent to make sure the area's homeless population is kept safe.

The center is working to make sure people prone to anxiety are handling the outbreak OK and children who are out of school and may have parents affected are doing well, said Dr. Valerie Pietry, Family Health Center’s chief medical officer.

The Family Health Center is also working to find potential funding opportunities to help its patients obtain the technology they need to interact with health providers online from home.

“We’ve found that our folks have been quite adaptive and have innovated on the fly,” said Lou Brady, the Family Health Center's president and CEO.

Up next – whenever the pandemic subsidies – could be another rush for community health centers. Postponed appointments will have to be rescheduled, and a new sector of the population could find itself out of work, without health insurance and needing to turn to these facilities.

“Some things can’t be replaced by tele-health,” Brady said. “We’re really trying to determine the capacity we can have between in-person and tele-health, and see what models we want to explore to give the maximum level of capacity.”

The revenue challenge

While shifting care as quickly as they can, community health center leaders have been dealing with another major challenge: A sharp drop in revenue they would normally see as reimbursement for routine services.

The Family Health Center is evaluating potential furloughs of 30 to 40 workers. Both that center and Kennedy, which doesn't foresee furloughs today, are working with legislators on Beacon Hill and in Washington, D.C., to secure more badly needed funding.

Federally qualified community health centers got roughly $1.4 billion from the federal CARES Act, spread among nearly 1,400 such centers nationally, according to the U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration. Most was given in the second of two phases in early April.

“This second amount buys health centers about five to six weeks of financial stability,” said Hunt, the president of the Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers. “That’s it.”

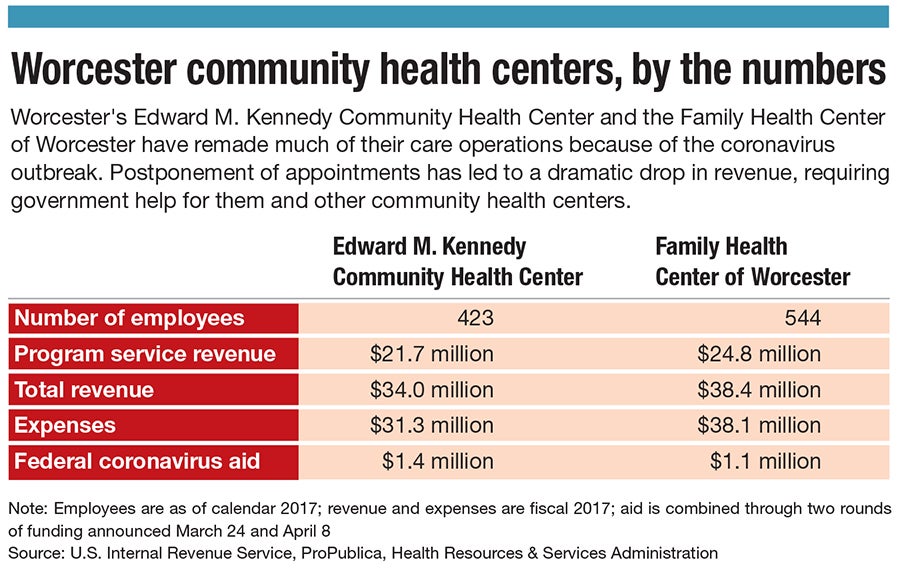

Hunt worries a loss of funding – even temporary – will undo decades of progress in caring for vulnerable populations. Kennedy has gotten about $1.4 million and the Family Health Center $1.1 million.

That money isn’t nearly enough. Tens of billions more have been requested, Hunt said. Kerrigan described progress as slow in getting the needed financial resources.

“For us, we’re a community health center,” he said. “We live on the margin all the time.”