Equity work has never been easy, and its often uphill battle has been compounded by the President Donald Trump Administration’s crusade to uproot DEI.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The concept of diversity, equity, and inclusion is hardly new. While the terminology may have not been the same, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 laid the foundation of what we know of today as DEI.

The Black Lives Matter movement, though widely popularized in 2020 following the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, began in 2013 in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman after he killed Trayvon Martin in Florida.

Systemic equity work has never been easy, and its often uphill battle has been compounded by the President Donald Trump Administration’s ongoing crusade to uproot DEI: labeling the work as illegal and immoral discrimination and threatening to pull federal funding from institutions and organizations staying committed to their equity principles.

Today, DEI practitioners are navigating misconceptions, fears, and layoffs, adapting their efforts to work around gatekeepers, zero-in on effective strategies, and make DEI a sustainable, systemic principle in the workplace.

“You have to be quiet. You can't ruffle any feathers. Folks are like, ‘Hey, don't bring any attention to my business, to my organization, to my company.’ I feel that people are walking on eggshells,” said Jessica Pepple, a Worcester-based DEI professional who most recently worked as the inaugural chief diversity and culture officer at RFK Community Alliance in Lancaster. “People have shrunk. You can't shine, so you have to shrink.”

For Pepple, navigating this risky landscape echoes a U.S. resistance movement from the mid-1800s: the Underground Railroad.

Fleeting commitments

After Floyd, a Black man, was killed by white Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin in May of 2020, U.S. business and organizational leaders felt as though they had to get on board with DEI, said Pepple.

“If you didn't, people would look at you sideways. People would think ‘Oh, so you're okay that the knee was on the neck?’” she said.

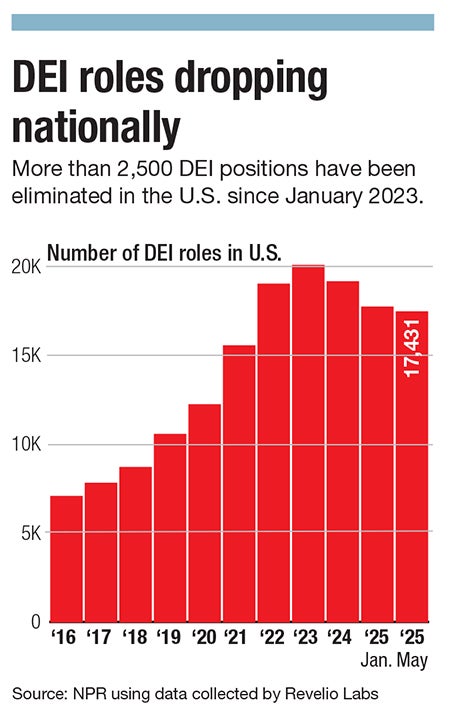

DEI roles had been steadily growing in the U.S. since 2016, increasing on average by about 1,000 jobs per year; however, the aftermath of Floyd’s death showed a clear increase in positions, according to research performed by Revelio Labs profiling 8.8 million companies.

In the three years from 2020 and 2023, the nation gained 7,842 positions before beginning to decline.

During this time period, DEI practitioners were working to make the work systemic: to go beyond just celebrating cultural holidays or dealing with affirmative action, and instead working to implement equity into every aspect of work from human resources to finance to marketing and to research, said Pepple.

But these professionals were often kept beyond arm’s reach by those in the positions of utmost power, she said.

Owners and CEOs often acted as gatekeepers from ingraining the work into the framework of an institution, she said.

“We didn't make DEI the DNA of an organization. It was still like an add on, like a Sunday dinner side or something like that,” said Pepple. “Since DEI was not the DNA of an organization … it was taken away like that. But that's what happens when you’re a side piece, right?”

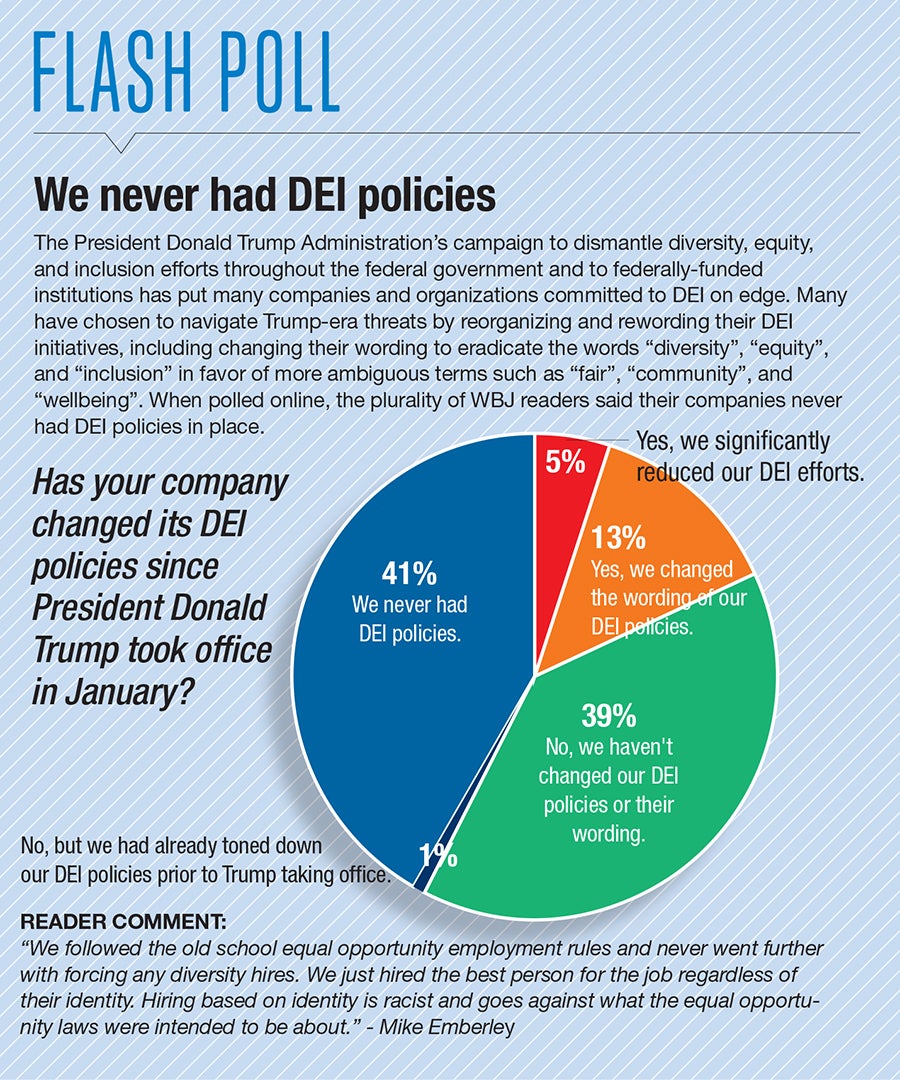

Since Trump took office in January for his second presidential term, there’s been a stark trend of companies scaling back or altogether dropping their DEI initiatives seemingly overnight, including household names like Walmart, Target, McDonald's, and Disney.

“It amplifies the real crux of the problem in a lot of these organizations and companies, in that it took nothing for you to break that commitment to making and creating a healthier workspace where everyone feels like they can excel,” said Soudie Tahmassebipour, chief strategist and founder of social impact consulting firm RE-ENVISION Consulting in Holden.

Losing DEI professionals

One of the biggest struggles and sources for frustration Tahmassebipour sees from DEI practitioners is DEI is often used like checking a box, from pre-2020 until today.

Both Tahmassebipour and Pepple have a resounding fear for newer and early-career DEI professionals, who unlike themselves, don’t have decades of job experience in other fields before entering into DEI work.

Tahmassebipour previously worked as a public defender, and Pepple has served in numerous leadership roles throughout the education sector. They both have had careers that drove them to become experts, and thus, would have ground to fall on if DEI were wiped away.

Younger practitioners don’t have that kind of experience, and many are struggling to find jobs, either landing their first DEI positions or finding new ones after being laid off, said Pepple.

America has lost nearly 3,000 DEI positions since 2023, according to Revelio Labs, which is based in New York City

Federal funding threats have caused fear around maintaining and progressing DEI, even those companies committed to doing the work, she said.

This shows up in changes in verbiage in missions, programming, and affinity groups.

Changing language

In reaction to federal threats, companies and organizations have chosen to take DEI out of their lexicon in favor of more ambiguous terminology that won’t raise alarm bells. While changing language does not inherently mean companies are abandoning their DEI practices – in fact, it can mean the opposite – leaders cannot do so while leaving their stakeholders and employees in the dark, said Valerie Zolezzi-Wyndham, CEO of Promoting Good, a DEI consulting firm out of Worcester.

Promoting Good works with leaders to tackle the evolving workplace landscape in an effort to cultivate inclusive and successful workplace cultures.

In April, Promoting Good launched a new leadership program called Cultiv8, a course using a proprietary assessment tool to measure the difference between the impact leaders think they have and how their workers actually experience them.

Though the timing of Promoting Good’s launch may seem to correlate with the federal administrative turnover, the two are actually quite independent, said Zolezzi-Wyndham.

Throughout the past eight years, Promoting Good has built an understanding of what traits contribute to inclusive leadership, said Zolezzi-Wyndham, but she wanted to take the next step and confirm their beliefs were backed by science.

“We could have just used our gut and built questions that got it those traits, like courage and curiosity, and it might have worked just fine, but we really wanted to make sure that the tool would have rigor behind it,” she said.

Thus, a year ago, Promoting Good partnered with The Bridgify Group, a Virginia-based research company, to conduct extensive literature reviews and engage the public in answering questions to help Promoting Good select and test its assessment questions.

“If leadership isn't doing the leadership work that they need to be better leaders for everyone, those [DEI] initiatives are going to fail,” said Zolezzi-Wyndham. “That's why we're focusing on leadership, because it's needed for the work to sustain itself.”

Though Cultiv8 wasn’t designed specifically to tackle DEI challenges during the Trump era, the program and Zolezzi-Wyndham work inherently readies their clients for it.

“You might be a leader that is changing the words to protect the work, but if you are not then communicating inclusively … then you are not providing the leadership that's going to have your team's trust,” she said.

DEI 2.0

The amount of uproar and policy charge surrounding DEI raises the question of whether this equity movement can sustain the vitriol.

The answer from Central Massachusets’ DEI practitioners is clear.

“However we frame [DEI] for the purpose of getting hired or for the purpose of the budget being approved, at the end of the day, this is important work. And it has to continue for the world to survive,” said Tahmassebipour.

Tahmassebipour sees DEI practitioners as having an opportunity, albeit a devastating opportunity, to think about how they communicate and how they share their messaging around the work.

Pepple foresees a large mess needing to be cleaned up once room exists for more equity work, but she’s confident the movement will bounce back.

“No doubt in my mind: It's coming back,” said Pepple. “And I pray that when it does come back, those practitioners form the narrative around DEI 2.0.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article incorrectly said Jessica Pepple was the chief diversity and culture officer at RFK Community Alliance. In actuality, she left the position in August.

Mica Kanner-Mascolo is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the healthcare and diversity, equity, and inclusion industries.