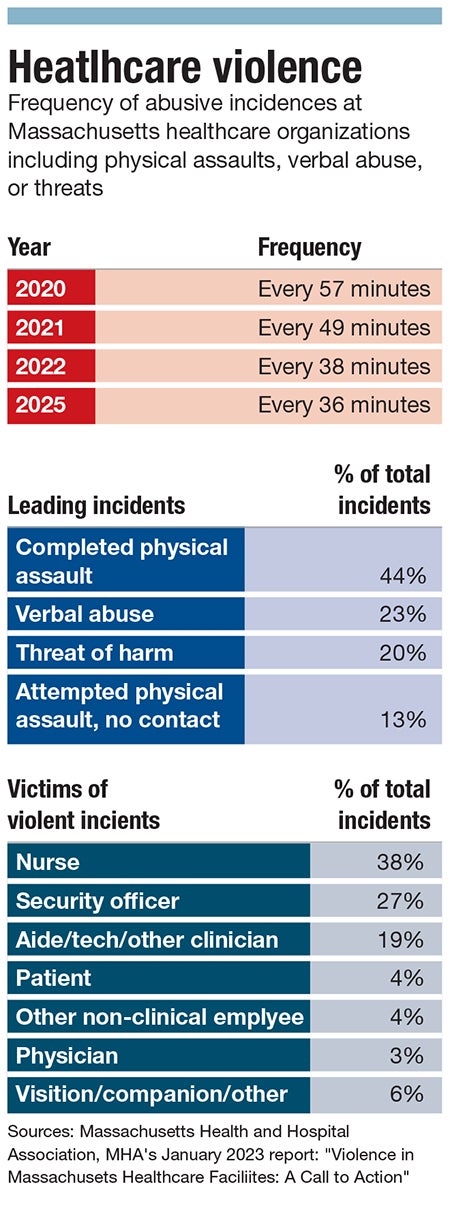

Every 36 minutes a Massachusetts hospital worker faces either an act of violence or threat.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Steve Walsh, president and CEO of the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association, delivered a grim message during an April legislative session: every 36 minutes a Massachusetts hospital worker faces either an act of violence or threat.

That frequency is up two minutes from when workers were exposed to physical assaults, verbal abuse, or threats every 38 minutes in 2022, every 49 minutes in 2021, and every 57 minutes in 2020, according to MHA data.

“The risk of harassment is constant,” said Elise Wilson, former nurse at UMass Memorial Health - Harrington Hospital in Southbridge. “We are the front line to everything that's going wrong in their life. That’s the problem.”

In 2017, Wilson was brutally assaulted by a patient while working a shift at the Southbridge hospital. Her assailant, Conor O’Regan, used a knife brought from home to stab her between five and six times during a routine intake, causing 11 stab wounds to Wilson’s face, neck, and left arm.

While she survived the near-fatal attack, Wilson was never able to return to nursing due the partial loss of function in her left hand. She has since traveled throughout the country, speaking about the reality of workplace hospital violence and advocating for legislation to protect workers against the assaults and abuse.

Yet, eight years later, the issue has only gotten worse.

“You can't spend a week in any hospital without hearing about a healthcare worker receiving either verbal assault or physical attempt at assault by patients. It truly is a crisis,” said Rozanna Penney, president and CEO of Heywood Healthcare in Gardner.

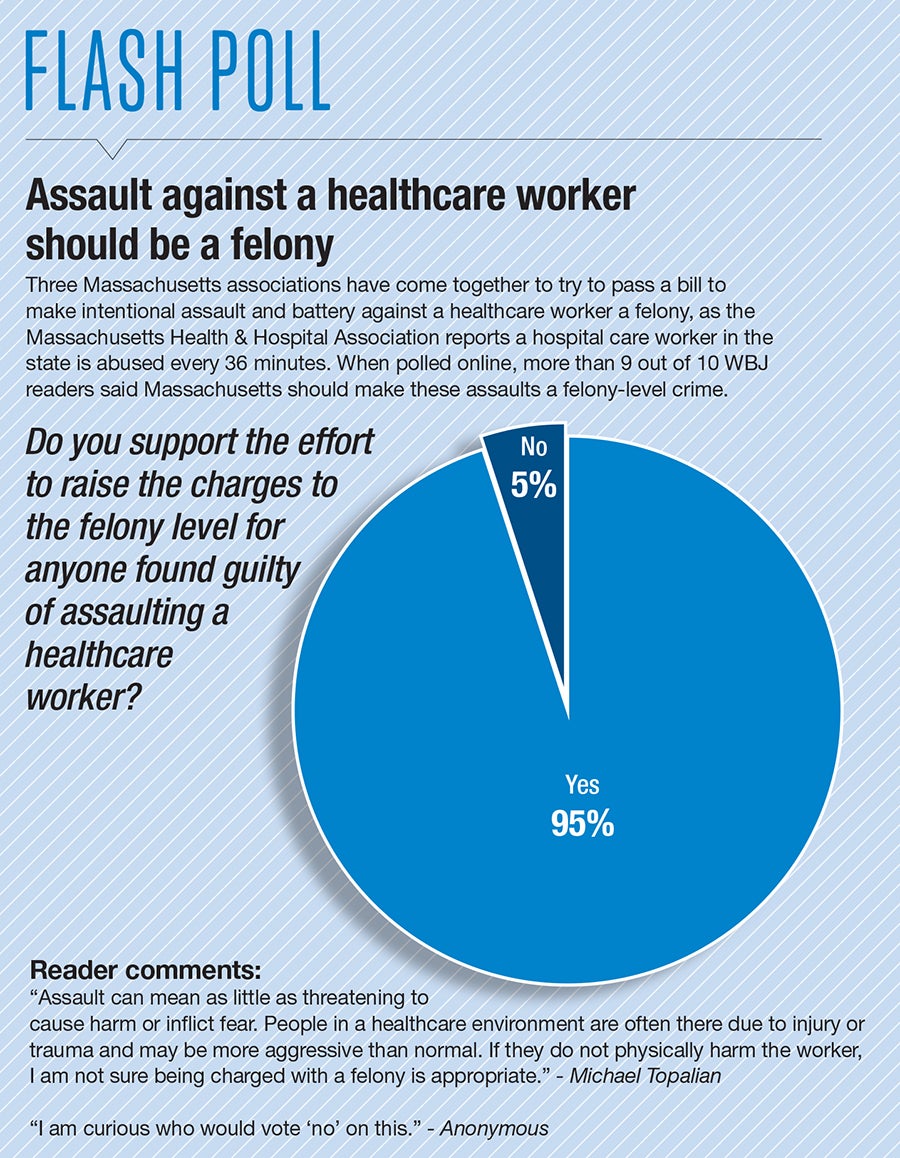

MHA, the Massachusetts Nurses Association labor union, and the 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East labor union are collectively pushing state legislation to increase assault charges against healthcare workers to a felony level while implementing mandatory hospital programs to decrease workplace violence, create violence prevention programming, and support those assaulted on the job.

A cultural shift

While hospital workplace assault is not a new issue, it has become acutely worse over the past few years, said Erin Proudman, senior director of emergency preparedness, safety, and transportation services at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester, the largest hospital in Central Massachusetts.

Long wait times to be triaged into the emergency room and then admitted into a hospital bed have proven to be major triggers of violence as of late, Proudman said.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought on a mass exodus of healthcare workers, with the National Council of State Boards of Nursing reporting an estimated 100,000 registered nurses left the field during the height of COVID.

Compounded by sicker patients showing up to ERs having postponed care during the pandemic and a lack of step-down care facilities, the workforce shortage has contributed to longer ER waits. Additionally, the closure of hospitals in the state, such as Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer, have exacerbated these issues.

“It's a very high stress, high energy, loud environment and can often cause individuals to get overly stressed, and really, they're not in the environment that they should be getting cared for,” said Proudman.

With those increased waiting times, many patients don’t seem to understand triage systems, said Penney.

Hospitals admit patients based on the severity of their ailments, resulting in some being admitted far before those who have been waiting longer. Penney said patients’ lack of understanding of this system can be extremely upsetting to individuals, who then act out in violent attacks or verbal harassment.

Furthermore, Wilson said a broader cultural shift is in part to blame for increased rates of violence.

“Go to the grocery store the day before Thanksgiving, and everybody's screaming and yelling at the cashiers,” she said. “That's not their fault that there's so many people there. Did you really think you were going to be the only one there?”

This wasn’t how things used to be, she said. Wilson sees the anger people express, whether it’s in the grocery store line or during a bout of road rage, has very much seeped into hospital.

Additionally, as medical knowledge has become more accessible through the internet, she said more people are coming into the hospital thinking they know what is wrong and what they need for treatment. When that differs from what their nurse or doctor tells them, many can quickly become agitated.

While Wilson observes men, ages 20 through 50, to be the main perpetrators of intentional violent assaults in the hospital, when it comes to those experiencing mental health issues, all ages can be aggressors.

“We've had kids in their teens that want to beat the shit out of us,” she said.

The pervasiveness of these abuses have only added to the workforce shortage in ERs, especially for support staff and nurses, said Penney.

Heywood Healthcare has been struggling to recruit workers for its emergency departments at Athol Hospital and Heywood Hospital in Gardner.

“They’re leaving emergency departments, the nurses who have been there for years. Even if they’re not leaving health care, they're leaving emergency departments because of how stressful that work has become,” she said.

Heightened security

In the summer of 2023, a patient stabbed a nurse in the neck at Heywood Hospital while being treated in the emergency department.

In direct response to the attack, Penney oversaw the system as it installed metal detectors, implemented the use of metal detector wands, and hired 10 new security guards to help ensure the safety of its hospital workers.

“Having the policy of not allowing the weapons has definitely decreased the prevalence of serious injury, and just seeing the amount of weapons that were confiscated when we first launched that program, [it was] kind of an awakening moment,” said Penney.

These operations present a sharp contrast to Wilson’s early days as a nurse at the now-closed Worcester City Hospital in the 70s. At the time, the hospital had only one guard who would walk around its buildings at night.

“You never had security. You never needed it,” she said.

The Heywood and Athol hospitals have code of conduct signage throughout their different departments, as do those at UMass Memorial Medical Center.

UMMC has implemented the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression assessment tool: a seven-item risk assessment providers use during their observations to determine a patient’s risk of violence within the next 24 hours.

The DASA assessment is typically used with behavioral health patients, but UMass decided to deploy the tool for all patients.

“What that does is it gives our caregivers the ability to sort of have a predictive tool of somebody who may be showing aggression within the next 24 hours, so that then proactively, they can put different measures in place.”

The hospital has additionally implemented caregiver safety training, including those teaching deescalation methods and physical protection techniques to prevent injury.

While training can help to a certain extent, Wilson said the burden of protecting hospital workers can’t fall on those workers themselves. They’re there to treat patients, not to fight off assaults and abuse.

Penney said it’s the same for individual hospitals and healthcare systems.

“The hospitals are doing everything they can, everything we can. I think everybody who works in the hospital understands how critical this issue is,” said Penney. “This cannot be just another thing the hospitals absorb and take care of on their own.”

There needs to be a more organized approach to support hospitals, she said. An example of that are the bills being pushed forward by three of the state’s anchor healthcare organizations.

Putting it in writing

The House and Senate bills, named “An Act requiring health care employers to develop and implement programs to prevent workplace violence”, aim to require healthcare employers to create and implement programs to prevent workplace violence while offering protections for employees who become victims of violence or assault and battery. The bills include penalties for non-compliant hospitals.

In addition to monitoring hospital compliance, the pieces of legislation would allow for assaults against a healthcare worker to be elevated to felony charges with up to a five-year prison sentence and fines up to $5,000.

MHA members have been asking for felony-level charges for years, said Emily Dulong, MHA vice president, government advocacy & public policy.

“By having this in the bill … it's the multi-pronged piece that assists in whatever work that folks are going to be doing, or are already doing on the ground,” she said. “This also adds a little bit of teeth to those.”

Knowing workplace violence and harassment can at times be nuanced when mental and behavioral health factors are at play, MHA is working to ensure those needing treatment for those conditions or those with cognitive diagnoses are not unduly punished through the bills.

The MHA has been working with the state’s Office of Health Equity and Community Engagement to address issues occurring because of language barriers or cultural differences.

“We want to make sure that folks don't use implicit bias or any sort of unintentional personal views that make their workplace violence prevention plans discriminatory in any way, shape, or form,” said Dulong.

While a felony charge clearly won’t stop all assaults and abuses, Wilson and others in the field believe it will make people think twice before acting violently or hurling insults. Not only does Wilson see these bills protecting workers, she sees them as gateways to better care.

“We need healthcare workers, especially ER nurses,” she said. “They're like the front line of the army. They're just gonna be out there to save you, and they can't do their job if they're threatened.”

Mica Kanner-Mascolo is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the healthcare and diversity, equity, and inclusion industries.