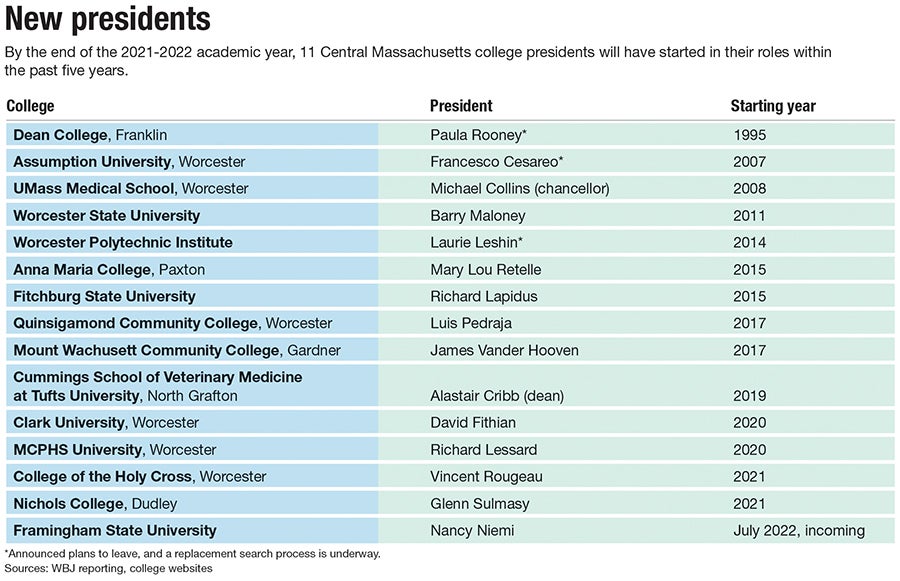

Since 2020, more than half of Central Massachusetts’ colleges and universities have seen a transition in top leadership, with eight presidents leaving or announcing their departure in the last two years.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Since 2020, more than half of Central Massachusetts’ colleges and universities have seen a transition in top leadership, with eight presidents leaving or announcing their departure in the last two years.

The trend has a variety of implications for higher education in the region, as 10 of the 15 leaders of local colleges have five years of experience or less at their respective institutions. Along with a loss of institutional knowledge with the outgoing presidents, the transition to a new president involves the arduous, yet critical, process of choosing a new leader.

“It’s a lot of engagement, communication, maybe even strategy,” said Kevin Foley, who chaired the presidential search process at Framingham State University. “This is probably one of the most important decisions that you can make for a campus.”

Framingham State announced its new president, Nancy Niemi, in December, about nine months after outgoing President Javier Cevallos gave his notice of retirement.

Most recently in March, Assumption University President Francesco Cesareo announced his plan to retire, just three months before the end of his term. Outgoing presidents Paula Rooney at Dean College in Franklin and Laurie Leshin at Worcester Polytechnic Institute also announced their plans to leave by the end of the 2021-2022 academic year.

All three of these outgoing presidents outpaced the national average tenure of a college leader, which is 6.5 years, according to the American Council on Education. That average is trending downward from 8.5 years in 2006.

Colleges follow an overarching template to hire a new president, but among the variations of that process, controversies have cropped up about the most effective way to pick a leader.

A process, potentially flawed

Typically, an independent search firm oversees the presidential hiring process, in collaboration with the institution’s leadership. A search committee is also formed, made up of about 10 to 12 individuals from throughout the community, which can include trustees, faculty, students, and alumni.

Members of the search committee are asked, usually by the board of trustees, to represent the entire college in the decision-making process.

“A part of saying yes [to serving on the committee] was being comfortable with the fact that the committee was going to represent such a broad array of viewpoints,” said Joshua Farrell, a professor at The College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, who served on the presidential search committee in 2020.

Including different groups’ opinions and priorities in the hiring process is as challenging as it is crucial. Colleges must walk a fine line between including their community in the selection process and maintaining confidentiality for the candidates.

Concerns over transparency in the presidential search process came to a head at WPI after Leshin announced she will leave to lead NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the end of the academic year.

In February, two faculty groups wrote letters to WPI’s administration, voicing concerns about how much representation faculty would have in choosing Leshin’s replacement.

Both letters emphasized the need for transparency and community engagement, as the institute is grieving seven student deaths in six months, at least three of which were suicides. The letter from WPI’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors, which is the largest professional faculty association on campus, specifically asks for faculty to be given a shared central role in the presidential hiring process.

“What the trustees have done in the last couple weeks is that they’ve been speaking to select faculty and staff about what they want in a president,” said Professor John Sanbonmatsu, president of WPI’s AAUP chapter. “However, unless there’s some kind of representation and unless the community has direct input into the search process, that’s insufficient.”

Listening sessions are a common tool colleges use to gauge what the community wants to see in a new president. Colleges typically aim to hold sessions with as many different groups on campus as possible, but, as Sanbonmatsu said, there is a limit to how much representation these sessions provide.

WPI has “been holding listening sessions, but unless faculty are elected to the search committee and the search is an open, transparent process, then our concerns will stand,” Sanbonmatsu said. “They could just ignore the feedback that they’ve been getting.”

WPI said in a statement it will appoint a search committee to include faculty, students, alumni, and trustees. In AAUP’s letter, the organization asks that faculty and graduate students be able to elect their representatives to the committee, rather than have them appointed by the board of trustees or an independent firm.

“The search process will be broad and consultative and will engage the entire WPI community as we balance the need for agility and confidentiality,” said the statement from WPI.

This balance is indeed a delicate one, as some officials argue greater transparency leads to less confidentiality for the candidates. It may deter some applicants to know their names will be publicized and their current employer will know they’re applying for another job. Most colleges keep all candidates confidential until they have chosen two or three finalists, who might come on campus to meet and talk with different groups in person.

“You may lack getting candidates if the 20 people that applied all of a sudden [have] their names [made] public. People might not want to apply,” said Randy Becker, who chaired the presidential search committee for Nichols College in Dudley that selected Glenn Sulmasy from Bryant University in Rhode Island to succeed Susan West Engelkemeyer.

Changing demands

Higher education is not immune to the current challenges of attracting talent. Six of the seven presidents who have left in the last two years have retired, with the seventh – Leshin – leaving for a job outside of higher education.

“It almost seems apropos of the Great Resignation,” Becker said. “With COVID the past couple years, it seems that people may be reassessing when they want to retire or when they want to make a move. It’s just a huge time of change.”

Leaders in higher education are faced with new pressures presented by the coronavirus pandemic, enrollment numbers, and equity issues, Becker said.

As demands on college presidents change, however, it is an opportune time for schools to choose a new leader to fit those evolving needs.

Holy Cross opened up its application pool to non-Jesuit lay people for the first time, electing Vincent Rougeau, who became both the school’s first lay and Black president when he replaced Philip Boroughs. In the last several years, the college has struggled with questions of racism, including its historical ties to slavery and its mascot, the Crusader.

Foley of Framingham State said the university had a particularly nontraditional pool of applicants, with some coming from the medical field and elsewhere outside of the higher education sector.

“It’s an interesting time for higher education,” Foley said. “It’s a great potential to really pivot, to look at nontraditional learners, or to look at different vehicles to continue to expound on the idea of higher learning.”