When they looked in their email a few weeks ago and found subpoenas from U.S. Attorney Andrew Lelling’s office looking into their relationships with marijuana businesses, leaders in communities across Central Massachusetts, and the rest of the state, were surprised.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

When they looked in their email a few weeks ago and found subpoenas from U.S. Attorney Andrew Lelling's office looking into their relationships with marijuana businesses, leaders in communities across Central Massachusetts, and the rest of the state, were surprised.

“Usually I don’t see a lot of federal grand jury subpoenas – it might be the first in my career,” said Shaun Suhoski, Athol’s town manager.

Even as communities like Athol, Worcester, Uxbridge, Leicester and Hudson scrambled to comply with the extensive demands for local records, it remains unclear exactly what the grand jury hopes to find.

“I can only surmise, like anyone else,” Suhoski said. “It’s not like it came with a letter explaining why.”

City and town leaders, as well as people within the state’s growing cannabis industry do have some guesses.

“The first thing that pops up in everybody’s mind is what’s alleged to have gone on in Fall River,” said Phillip Silverman, a Boston-based attorney with Vicente Sederberg LLC, a national firm focusing on the cannabis industry.

In September, Lelling’s office charged Fall River Mayor Jasiel Correia with extorting bribes from cannabis businesses. But Silverman said it’s not clear how subpoenaing municipal records would turn up that kind of illegality.

“It’s not exactly like there’s going to be a document that lays out the corrupt scheme,” he said. “Maybe they’re just dotting all their i’s and crossing all their t’s.”

Illegal host agreements

Aside from gross corruption, Silverman said, the other common assumption in the industry is Lelling is investigating violations of host community agreements, an aspect of the state’s regulation of the cannabis industry that has been highly controversial.

“I find that really hard to believe,” Silverman said, noting HCAs are a matter of state law and, if the federal government wanted to intervene in cannabis sales, it could just start enforcing federal drug laws, which it has so far declined to do in states legalizing recreational cannabis.

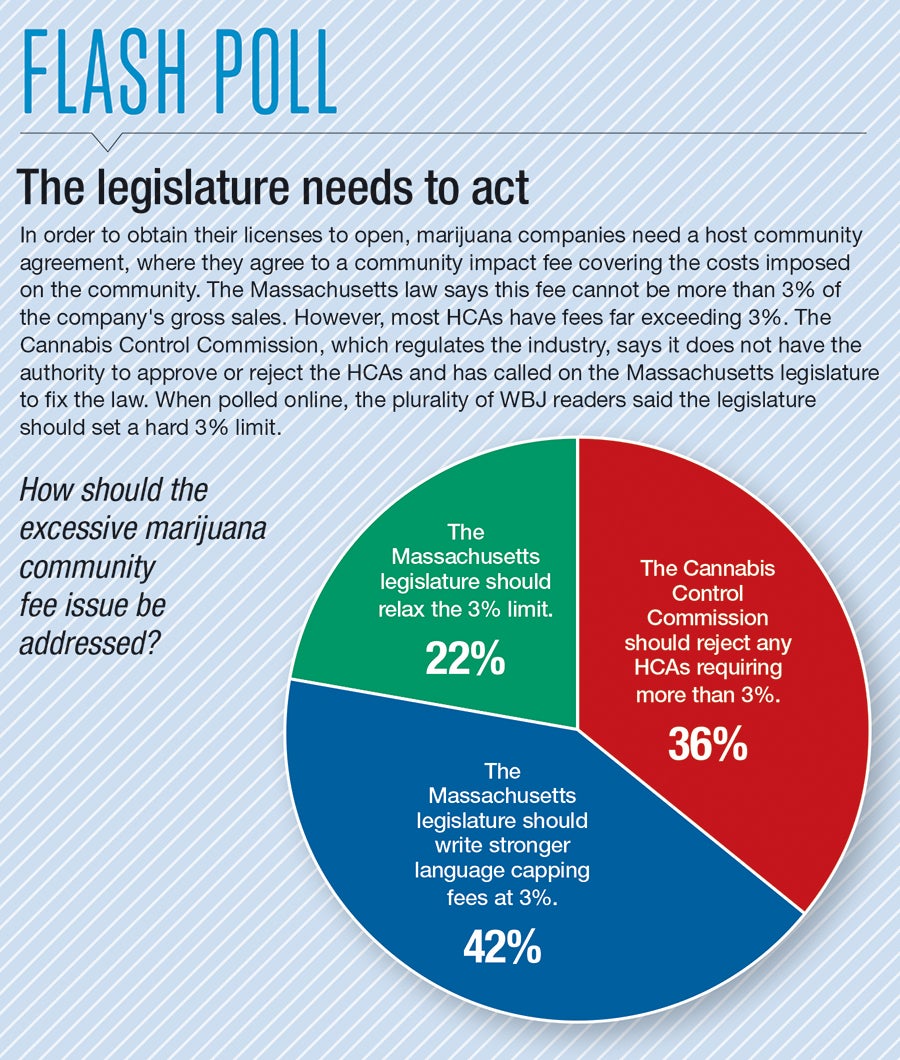

In any case, the investigation has stirred up new discussions of the HCAs, which in some cases seem to make demands on cannabis businesses to go beyond what state law allows. The law limits impact fees charged by cities and towns to 3% of a company’s gross sales and requires they only represent actual costs related to having the businesses in town. Yet a number of local agreements include additional requirements.

Steven Hoffman, chairman of the industry regulator Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission, wouldn’t comment on the federal investigation, but he said the broader issue of HCAs is important to the CCC.

Hoffman said some agreements include flat fees rather than payments based on sales, donations to outside charities, or even require a company to pay for municipal expenses like a new fire truck. While the CCC believes these provisions violate the state law, the agency has determined it doesn’t have the authority to intervene in the contents of the local agreements. It has asked the Massachusetts legislature to grant it that authority, and a bill on the topic is now moving through the legislative process.

The inclusion of expensive demands in the HCAs is particularly troubling because Massachusetts has sought to make sure small businesses and entrepreneurs from disadvantaged backgrounds have access to the cannabis market, Hoffman said.

“The issue absolutely is a significant barrier in the way of equity and diversity,” he said. “It’s a very important issue to us.”

Matt Simon, New England political director for the Marijuana Policy Project and a member of the drafting committee that wrote the state’s law regulating the cannabis industry, said he had expected state regulators would review the host community agreements.

“It certainly would have been a smoother and better and more rational process if they had been reviewed for compliance with state law all along,” Simon said.

Simon hopes the federal investigation will lead to renewed discussion about improving the process, as no other state has a similar way of organizing approval of cannabis businesses.

“We are actively encouraging other states not to follow this model,” he said. “This has been one raincloud that has sort of hovered over the process and prevented the law from being as successful in certain respects as we would like.”

Extensive subpoena requests

While these questions continue to play out, several local officials said they’re not particularly worried about the federal investigation and are complying with the subpoenas’ demands. Worcester City Hall spokesman Michael Vigneux described Lelling’s requests as pretty extensive and said the city is providing the requested documents.

Hudson, one of the first places in the state to have a recreational dispensary open, had already sent the requested documents in by Nov. 12, though Executive Assistant Thomas Moses said it was no small task.

“It was a little unusual, because they asked for draft documents, which typically we delete,” Moses said. “There’s no reason to keep them. They’re not public records.”

Still, Moses said he was able to gather many draft versions of relevant paperwork, along with notes on internal deliberations and other materials.

“I probably had hundreds of emails that said ‘Can you meet at 2:00?’ ‘No, I can’t, let’s move it.’ They wrote the subpoena so broad as to include those, so I had to find them,” Moses said.

In terms of the contents of Hudson’s HCAs and its compliance with state law, Moses said the first agreement the town made with a company did include a provision asking it to make a donation to a nonprofit of the company’s choice.

Moses said the thinking was this would be a way to support organizations related to fighting drug abuse, though the agreement did not specify the nature of the group. In subsequent agreements with other businesses, Moses said the town did not make any request of that kind.

He said the town would be fine with a demand to eliminate the request for a donation.

“The worst I think that could happen to Hudson was they’d find that one agreement, and they’d say take that donation out, which we wouldn’t have a problem,” he said.