A key tool to help decarbonize New England’s electricity grid has already been in operation for over a century.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

While solar and wind power tend to get a lot of the attention in the quest to transition to clean energy, a key tool to help decarbonize New England’s electricity grid has already been in operation for over a century.

Now owned and operated by Westborough-based Great River Hydro, 13 dams in western New England were the original source of electricity for manufacturers across Central Massachusetts and beyond in the early 1900s.

“We've been renewable since before renewable was really thought about as a thing,” Erin O’Dea, CEO of Great River Hydro said. “These hydro assets have always been part of the energy mix in New England.”

Under the company’s stewardship, its hydropower facilities play an important role in keeping homes powered and keeping machinery in the region running. Now embarking on a study to modernize its facilities, Great River is seeking to ensure its infrastructure continues to power New England for decades to come.

Powering the Industrial Revolution

Great River’s origin trace back to the late 1990s, when governments began to deregulate the generation-side of the electricity market in an effort to drive efficiency and cost savings by making the market competitive, said Brandon Kibbe, vice president of external affairs for Great River Hydro. After the dams went through a few different owners, Great River was formed in 2017.

While Great River is a relatively young company, some of its facilities are more than 100 years old, like Vernon Station, located on the Connecticut River and stretching between Vernon, Vermont, and Hinsdale, New Hampshire.

Water played a key role in powering the Industrial Revolution in New England from the get-go, but the creation of long-distance, high-voltage power lines meant Central Massachusetts’ factories no longer needed to rely on their own connections to the region’s rivers, Kibbe said.

“In 1909 when the Vernon Station was built, this was the first place that high-voltage, alternating current was dispatched anywhere in New England,” he said. “The power from Vernon Station went to places in Central Massachusetts like Fitchburg, Leominster, Millbury, and Worcester, where there were centers of industrial activity at that time. So the very first transmission lines in New England connected Vernon Station to these industrial hubs.”

Today, the company’s facilities are controlled at a central hub in Vermont, but the Westborough office allows the company to tap into the Central Massachusetts’ region talent pool for the administrative, marketing, IT, and other roles handled by its headquarters.

“Through the various iterations of ownership, there's been a Westborough presence,” Kibbe said. “So it's part of that legacy and for continuity with the folks that have been involved. It’s also about access to talent. It's access to decision makers. It's access to a lot of the important things that happen in Massachusetts, which is the largest consumer of electricity in the region.”

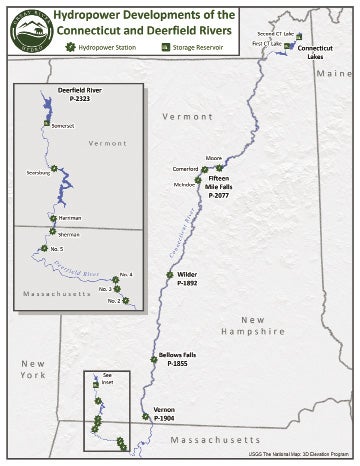

Giant batteries

Great River Hydro’s portfolio is located exclusively on the Connecticut and Deerfield Rivers, stretching from near the Canadian border in New Hampshire down to the northwest portion of Massachusetts.

Its assets account for about 23% of installed hydropower in New England, making it the largest provider in the region and a major national player in the space, Kibbe said. With 13 generation stations and three water storage reservoirs, its facilities produce 1.6 million megawatt hours a year, enough to power about 213,000 homes.

Those reservoirs are a key part of the importance of Great River Hydro’s infrastructure to the overall New England grid, as they basically serve as large batteries ready to provide power at a moment’s notice, Kibbe said.

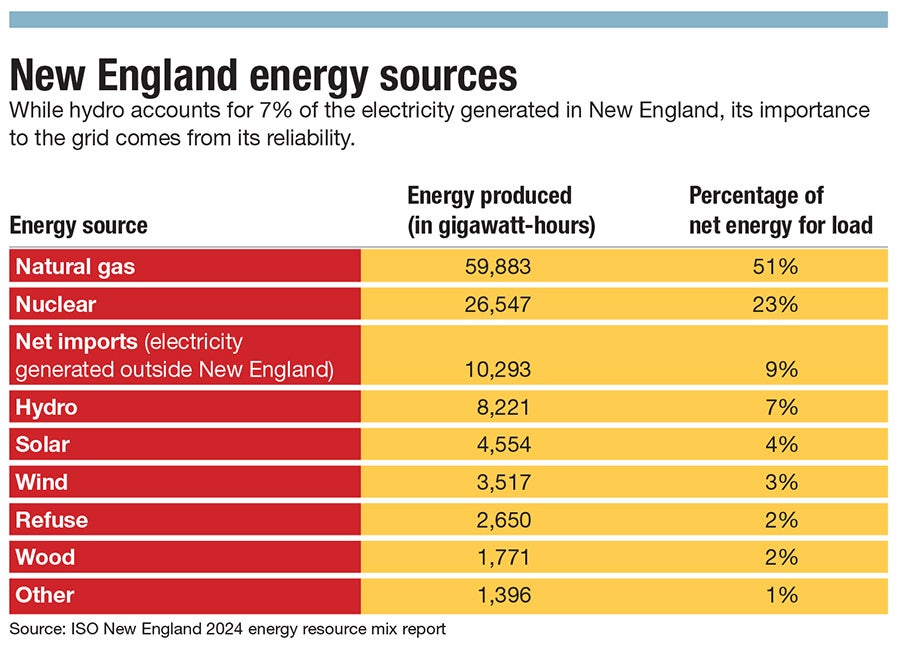

While hydro accounted for 7% of New England’s net energy load in 2024, according to regional power grid operator ISO New England, it’s this reliability that allows hydro to play a critical role in complementing less-reliable sources like wind or solar, which require specific environmental conditions to be able to generate electricity.

“Most conventional hydropower, when most people think of it, is what they would call run-of-the-river, which is simply water flows down river, goes through the station, and then keeps going,” Kibbe said. “Reservoir storage means we can actually store the water as it flows down river, and then dispatch the generation when the highest demand periods are.”

Great River has 104 employees across its facilities. The company has both union and non-union employees, with its union employees including electricians, mechanics, and technicians.

The employees “have been with these assets for a long time, so they really take a lot of pride in them,” said Mike Carroll, maintenance manager at Great River’s Deerfield River sites. “It's very helpful to have people who work in an area that really care.”

Powering the future

While newer green energy technology has been subject to skepticism and scrutiny from the President Donald Trump Administration, hydropower’s long-standing history and infrastructure in the county has allowed it thus far to avoid being lumped in with wind and solar. Hydropower was included in a list of domestic energy resources which the administration outlined in an April executive order seeking to lift regulatory burdens on developing American-based energy sources.

“Hydropower, compared to other renewable resources, isn't as challenging for the current administration,” said Alison Magoon, senior program manager on the Net Zero Grid Team at Massachusetts Clean Energy Center. “What I don’t think the hydropower industry has seen, though, is significant commitments from this administration to funding. They haven’t necessarily seen cuts, but they haven’t necessarily seen all of the hope they might be looking for.”

More than 115 years after Vernon Station first began powering manufacturing sites in Central Massachusetts, the state continues to see hydropower as an important resource. Earlier in 2025, MassCEC awarded Great River $93,000 to help it embark on a study to modernize and rehabilitate its five power stations on the Deerfield River.

The dams “have been here for over 100 years,” O’Dea, CEO of Great River, said. “We want to set them up for the next 50 years. So what does that mean in terms of how we spend the capital investment? That's what this study is allowing us to do. It might be putting in different types of units that could be more efficient or that could increase the output. Given the age of the units, we want to step back to evaluate which path we want to go.”

Sometimes modernization can be as straightforward as replacing parts like turbines with new models, said Sarah Cullinan, senior director of the Net Zero Grid Program at MassCEC.

Other ways to maximize production and minimize negative impacts include new lubricating oils, which are safer for the surrounding environment. Fish ladders, key in preventing dams from blocking migration, can be updated in ways beneficial for the fish and dam operators.

“Newer methods of fish passage don't require as much downtime for the facility, so you get increased generation,” Cullinan said.

Eric Casey is the managing editor at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily reports on the manufacturing and real estate industries.