While organized labor has historically been hallmarked by the male-dominated trades, unionized women seem to be fueling a new era in the movement, particularly in industries highly impacted by the coronavirus pandemic like health care, education, and hospitality.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

While organized labor has historically been hallmarked by the male-dominated trades, unionized women seem to be fueling a new era in the movement, particularly in industries highly impacted by the coronavirus pandemic like health care, education, and hospitality.

In January alone, 61 union strikes and labor protests were occurring around the country, nearly double the 31 from January 2021, according to Cornell University’s new Labor Action Tracker. For all of 2021, the nation had 1,029 strikes and protests, including 43 in Massachusetts.

Working women still have a lower rate of unionization than men, but the gap between men’s and women’s union membership has been closing since the 1980s, tightening from a 10-percentage-point to a 0.5-percentage-point difference in 2019, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“A lot of the issues that some people might predominantly say are women’s issues are our issues. They’re workers’ issues, whether it’s paycheck fairness or access to affordable childcare,” said Steven Tolman, president of Massachusetts’ AFL-CIO chapter.

Central Mass. falls behind

This change has been reflected in leadership, at least nationally. Women make up roughly 40%, on average, of leadership teams in America’s six top unions, according to data provided by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

More women have risen to high-profile, top leadership positions in labor. In the summer, Liz Shuler was named the first female president of AFL-CIO, the largest union federation in the U.S., joining other female leaders like Sara Nelson, the international president of the Association of Flight Attendants, and Mary Kay Henry, who leads the Service Employees International Union.

“There’s a rise of womens’ leadership within our own rank and file,” said Merrie Najimy, Massachusetts Teachers Association president. “We have been transforming as a union for the last eight years. We’re really changing our culture to put more of the authority and responsibility in the hands of [our] members.”

The MTA has been pushing diversification efforts over the past decade, and Najimy emphasized the importance of diverse leadership as unions advocate for the needs of all their members.

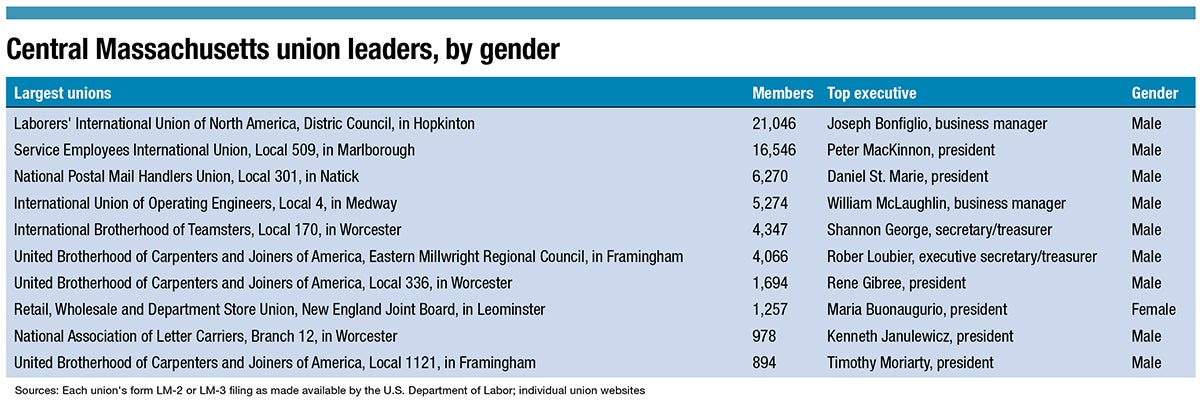

However, Central Massachusetts union leadership is still overwhelmingly male-dominated, despite women’s growing presence in organized labor.

Of the 12 largest unions in the region, only one is led by a woman. At least four of the top 10 unions have executive teams that are 100% male, with most women in leadership teams holding the position of recording secretary, according to unions’ individual websites.

New leverage for women in unions

Women in labor gained traction in Central Massachusetts last year with the Saint Vincent Hospital nurses of Worcester successfully reaching a contract after an historic 10-month strike. The Saint Vincent nurses were led by nearly all women, as their union, the Massachusetts Nurses Association, has a nearly 90% female executive team.

“I feel like we have a little bit of a bigger platform right now,” said Katie Murphy, president of the MNA.

The coronavirus pandemic has played an instrumental role in widening that platform, said Murphy, as women and people of color make up the majority of work considered frontline in the pandemic. Women make up 75% of health and education workers and 51% of hospitality workers, according to the most recent data from BLS.

In a phenomenon known as the Shecession, millions of women have left the workforce since COVID-19 first struck, with female employment rate 5.7% lower than pre-pandemic levels, according to an October report from the Massachusetts Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development.

This drop created a labor shortage in female-dominated industries like health care, making women workers less replaceable and providing more leverage for women to make labor demands, and an opportunity for unions to make those demands on behalf of workers.

“We’ve seen that corporations are more than willing to throw their frontline workers out there and not take responsibility for making as safe of an environment as possible,” Murphy said.

This turned the tables on the worker-employer relationship, said Najimy from the teachers union. Before they were considered essential workers, women-dominated industries have faced substantial challenges in getting their voices heard.

“Women’s work is predominantly cares work,” said Najimy, referring to the large percentage of women in healthcare and education. “It’s the system of powers we work under [that] are largely dominated by men and white men that disrespect women, that disrespect their labor, and that actually disrespect cares work.”

The MTA’s most recent endeavors have focused on uplifting education support professionals, specifically paraprofessionals in schools. Over the past year in Shrewsbury, paras have rallied for a contract to raise their wages.

“Traditionally, maybe we felt that our voices weren’t as loud, but I think when we have to stand up and be counted, people do,” said Murphy.