The Boulevard Diner now stands as Central Massachusetts’ sole independently-owned diner operating with any kind of 24-hour model.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

What was once the gathering ground for studying college students, bleary-eyed third shifters, and tipsy club-goers alike has been quietly slipping away, as the 24-hour diner has been gradually replaced with round-the-clock fast food options and delivery drivers available at the touch of a button.

But in Worcester, a little red-and-beige diner on the city’s bustling Shrewsbury Street has stood the test of time.

The Boulevard Diner now stands as Central Massachusetts’ sole independently-owned diner operating with any kind of 24-hour model. Opened in 1936, the diner is currently open overnight Thursdays through Sundays. As the city’s oldest diner, the Boulevard has kept the lights on 24/7 for most of its nearly 90-year run, but the COVID-19 pandemic changed that; and the Boulevard isn’t alone.

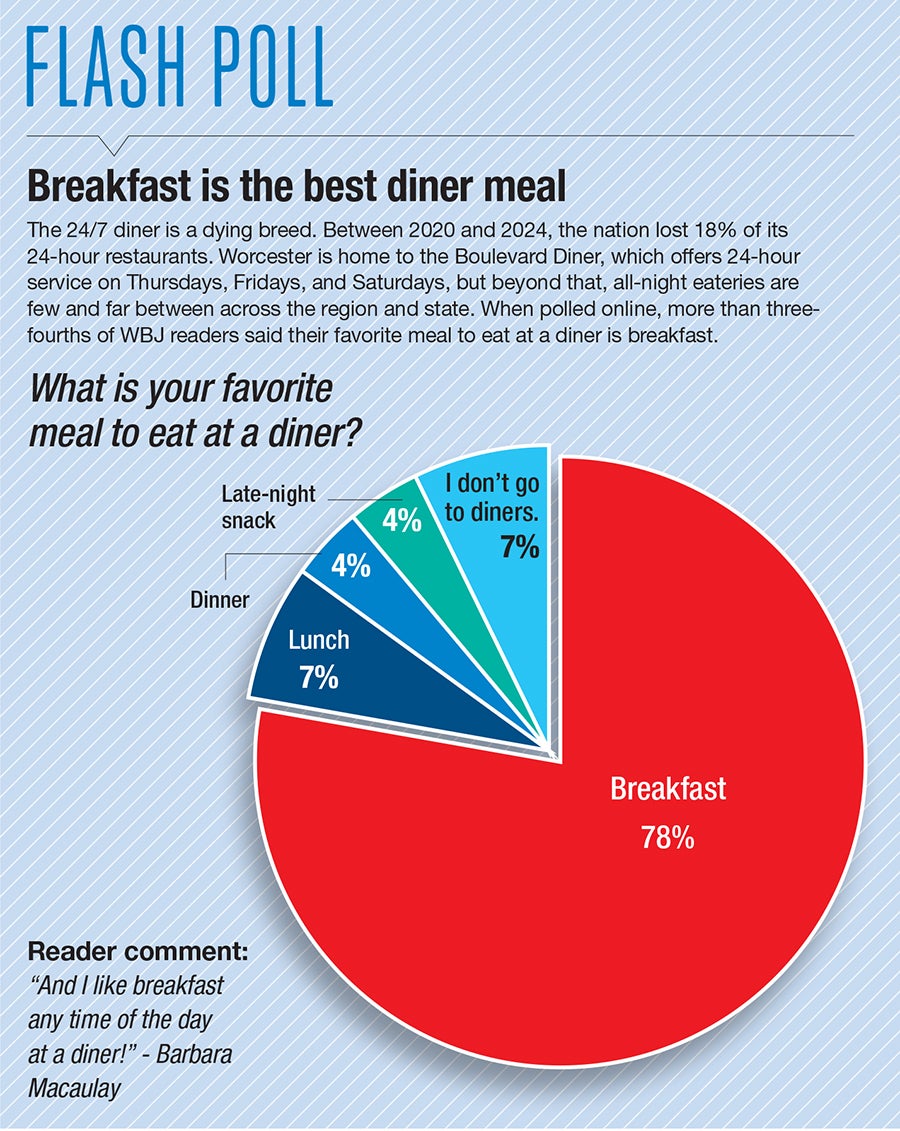

Between 2020 and 2024, the U.S. lost 18% of its 24-hour restaurants, according to the business review platform Yelp. While Worcester, once a 24/7 dining pioneer, has almost completely lost its round-the-clock restaurant infrastructure, hope of a resurrection is not out of the picture.

A Worcester origin

The modern concept of the 24-hour diner has deep foundational roots in the city of Worcester, drawing from the horse-drawn lunch wagons of the 19th century, said Bill Wallace, executive director of the Museum of Worcester.

In the late 1800s, Samuel Messer Jones moved his lunch wagon company from Providence to the burgeoning manufacturing hub of Worcester.

Worcester’s horse-drawn wagons, which later were shipped throughout the country, were mainly built to feed employees who were newly working third-shift hours as factories began to utilize electricity, staying open at night.

“These horse-drawn lunch wagons, by local ordinance, could park and meet the needs of people,” said Wallace. “Then they can move on to another location, just as a food truck would today.”

Gradually, the traveling wagons became more popular, with more people working late and more people wandering the streets after concerts and events. As the dining carts evolved, they were allowed to become stationary, making them gathering grounds and pillars of their communities, said Wallace.

“They take the wheels off. They hook up to power … They grow over time and service a neighborhood need, whether it's outside of a factory or an office area. They were the go-to spot,” said Wallace.

The same can be said for Boulevard Diner. While it used to have a number of fellow 24-hour peers such as Miss Worcester Diner and Kenmore Diner, Boulevard still has a steady stream of local late-night eaters who depend on it.

“There's always been a crowd out there late at night,” said Boulevard Owner James George.

But there has been one, noticeable hiccup in that trend throughout the diner’s history.

The COVID effect

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the restaurant industry hard. The National Restaurant Association estimates within the first six months of the pandemic, nearly 100,000 restaurants throughout the nation closed either temporarily or permanently. While the height of COVID has passed, its lingering impacts are still felt by traditional restaurants and the 24-hour dining model.

In the past five years, the two biggest expenses for restaurants have skyrocketed: food costs have risen 45% while the price of labor is up 40%, said Steve Clark, president and CEO of the Massachusetts Restaurant Association. Both have presented seismic financial hurdles for restaurants operating standard dining hours, never mind a 24-hour model.

Furthermore, Clark credits a great part of the decline of 24-hour dining to a very specific realignment within the restaurant industry.

“For decades, restaurants always thought that they needed to be open all the time because a consumer or a guest might come to be served,” he said.

Not anymore. Profitability challenges have forced owners to restrict open hours to those most popular in order to maximize revenue, especially cutting hours that, ironically, have become slower due to the very changes restaurants made to survive the pandemic: delivery services.

“We taught people how to enjoy restaurant product at home,” said Clark.

Most restaurants generate between 20% to 25% of their revenue through delivery services, Clark said.

COVID made more people more comfortable at home with options like DoorDash and Uber Eats, making ordering deliverably easier than ever.

“All of a sudden, the demand for the 24-hour diner is probably not what it was 10 years ago, 15 years ago, because there's just less people out there,” said Clark.

The rise in food delivery apps is the number one reason the nation is experiencing a decline in 24-hour dining, said George, the Boulevard’s owner. Fast-food chains like McDonald’s have designated courier parking spots for delivery app drivers.

Still, the Boulevard typically needs to shut off its delivery apps during the third shift because of customer volume in-house. This demand for third-shift service has pushed George to open up overnight operations over the past few years.

Family ties

George’s family has owned the Boulevard for the past 60 years, with James’ father John purchasing the diner with a business partner in 1965, shortly before assuming sole ownership in 1969. Since then, the diner had operated 24/7 until John became elderly and then passed in 1993. James officially took over the business in December 1999 and immediately opened up 24-hour service again in 2000.

George originally revived the business model in tribute to his father.

“I said, ‘Dad, I'm going to open up the diner. I'm going to go back to 24/7, the way that you always wanted to see it. And that's what I did all those years right up to the pandemic,” said George.

Operating in a bona fide college town, the Boulevard frequently hosts students studying late at night, and that has stayed consistent both pre- and post-pandemic. What has more so changed has been a decline in those who partake in nightlife frequenting the diner.

Pre-COVID, the Boulevard saw a lot of club and bar owners and third-shift workers come eat after they got off work, as well as club-goers sobering up before heading home. But today, fewer people engaging in nightlife; clubs are closing due to rising rent and insurance prices and young people drinking less post-pandemic, according to an April story in The New York Times.

The Boulevard has seen that shift affect its clientele demographics in real time.

The issues of the rise of delivery apps and the decline in nightlife have been compounded by the limited workforce availability.

“Employees didn't come back with that joy. Didn’t come back with that spark,” said George.

Just getting employees to apply to the Boulevard post-pandemic has been challenging, let alone finding staff for the third shift, he said.

Luckily for George, the diner is small and he has family and a small group of trusted employees to run the restaurant. As business has picked back up, they’ve been willing to take on those overnight shifts that others shy away from.

Opening back up?

When it comes to opening back up to 24/7, the George family is split. Gabriella George, James’ daughter who works nights, hopes the restaurant extends its hours once again. But James isn’t too keen on the idea.

Never shutting off equipment like dishwashers and grills predictably makes them wear down quicker, and replacing them is no cheap endeavor. Furthermore, it can be a financial gamble as to whether the diner recoups the money it pays staff depending on how busy any given night is.

But Clark thinks the pendulum may start to swing in the opposite direction, and 24-hour establishments may start to see more customers in the not-too-distant future.

“If you look at the Gen Z-ers, they might have different desires now at age 20 than they do at 30. Things might change. They might change. They might not always want to stay at home and have a quiet existence with their friends. They might want to go out again,” he said.

The country has continuously gone through economic and social phases that have shifted consumer preferences and abilities, Clark said. The Roaring Twenties was followed by the Great Depression and the Baby Boom starting in the 1940s was followed by the rebellion of the 60s and 70s.

“There's always these generational swings that happen throughout history. And why wouldn't that happen again?” said Clark. “Why wouldn't that apply to 24-hour dining?”

Mica Kanner-Mascolo is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the healthcare and diversity, equity, and inclusion industries.