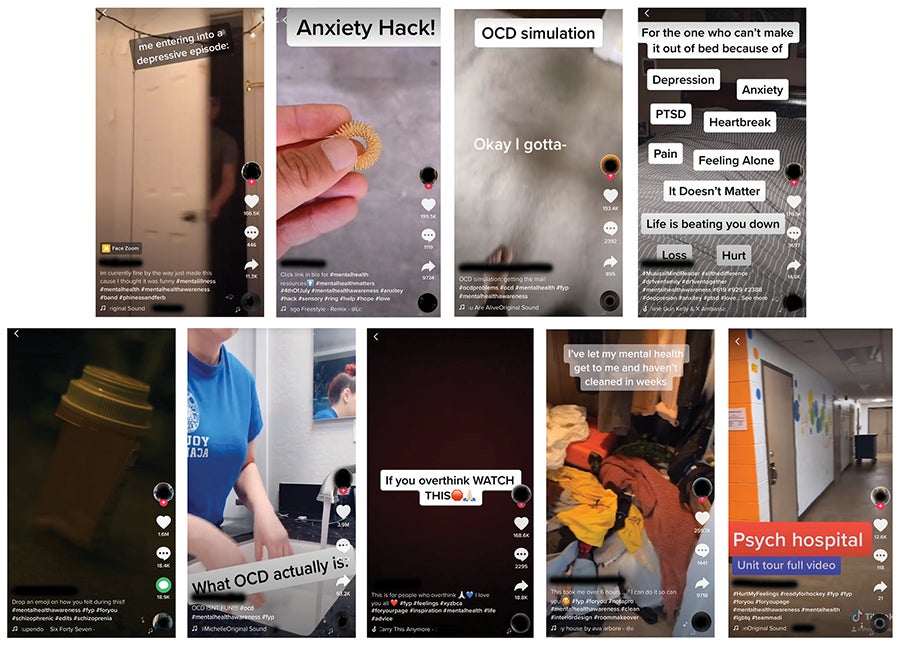

TikTok is many things: a social media app specializing in snappy, one-minute-or-shorter videos; an opportunity for unknown citizens of the internet to go viral at a dizzying clip; a never-ending loop of practical jokes and dog videos. For some, it has become a place to learn about and commune around mental health.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

TikTok is many things: a social media app specializing in snappy, one-minute-or-shorter videos; an opportunity for unknown citizens of the internet to go viral at a dizzying clip; a never-ending loop of practical jokes and dog videos. For some, it has become a place to learn about and commune around mental health.

At a time when mental health awareness has entered the vernacular, it’s not surprising the app’s users would use the platform as a place to gather and share their often intimate experiences with mental health challenges. The #mentalhealthawareness hashtag has more than 2.1 billion views on TikTok.

But even a subcommunity centered around something as noble as promoting awareness, education and comradery for those experiencing mental health issues is subject to the same dangers as communities centered around any other commonality, among them being safety risks, echo-chamber producing algorithmic feedback loops, and misinformation.

A young user base

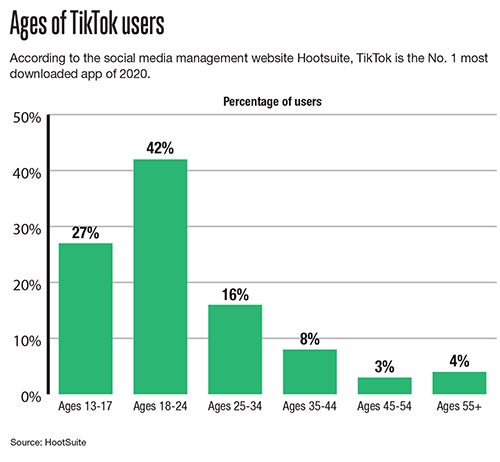

The app, which launched worldwide on Aug. 2, 2018 after merging with the app musical.ly, is still in its relative infancy, compared to other behemoths like Instagram, Twitter or Facebook. But over the last year – and especially since the coronavirus pandemic relegated many to their homes for months on end – its popularity has skyrocketed.

Initially cast as an app for teens and college students, the user base still remains demonstrably younger, even as older folks and Generation X celebrities join its ranks. Social media advertising agency Wallaroo Media reports, in the United States, 80% of TikTok users are between the ages of 16 and 34, with 60% of TikTok users part of Gen Z.

As with any other social media application, whether a forum like Reddit or a blogging platform like Tumblr, or something in between, like Facebook, subcommunities have developed, largely through the use of hashtags and TikTok’s algorithm. The latter has been renowned for its ability to suss out exactly what users are interested in and feed it back to them almost nonstop through the app’s Four You page, an endless scroll of videos very apparently chosen based on how one interacts with the videos before it. Did you share two TikTok videos of golden retrievers with your friends today? Expect to see a lot more golden retrievers in the near future.

The algorithm is so specific subcommunities have even developed around hyper-specific, bizzarro subjects like – this is not a typo – canned beans, or the date Aug. 27.

The same is true for posts about mental health, whether they are broadly about so-called mental health awareness, or specific, like meals one eats during eating disorder recovery.

An echo chamber of advice

Dr. Charles Sachs, a developmental clinical psychologist who is a professor at Framingham State University and has a practice where he works with children, teenagers and adults, said while such a precise algorithm is the sign of a good programmer, such feedback loops “put you into this constant stream of being exposed to just that one topic, and I think it can be overwhelming after a while.”

But can one actually be too overexposed to their own mental health challenges? Sachs, who noted there isn’t yet enough research to show exactly what kind of impact TikTok usage or mental health-centered internet communities might have on one’s development, said overexposure to a mental health advice echo chamber could potentially do damage to a young person’s sense of identity.

“I hope that whatever anyone’s mental health struggles are, it doesn’t define the totality of who they are,” Sachs said. “And so if it does, then it’s probably they’re missing out on other facets of themselves and facets of their identity.”

Especially for young people, “the traditional expectation is that you’re exploring and developing your sense of identity during your adolescent years, in particular, and into young adulthood,” he said.

Not just peer-to-peer

TikTok’s mental health awareness community is not just Zoomers and Millennials sharing videos about what it feels like to be depressed, or lamenting the challenges of various mental health diagnoses. A handful of TikTok therapists have made a name for themselves, doling out everything from stress management tips to diagnostic criteria for adult ADHD to psych ward video tours. They occupy a thin line between explaining and glamorizing mental health challenges, packaging them with cutesy dances, catchy songs and flashy video editing TikTok is known for.

By and large, their reception has been positive, receiving glowing write ups from magazines and websites targeting adolescents. Think: teen magazines.

While some of those users, who frequently identify themselves as licensed mental health care providers, note their posts are not a substitute for therapy and they aren’t providing formal diagnoses, much like a sponsored Instagram post, those disclaimers are inconsistent and vary in substance.

In that vein, Sarah Cavanagh, associate professor of psychology at Assumption University in Worcester, wrote in her recent book “Hivemind” about how, in her words, social technology like smartphones and social media have amplified both the positives and negatives of people’s ultrasocial selves.

“I sum up my conclusions with a principle I call, ‘Enhance, don’t eclipse.’ That is, the healthiest outcomes are predicted when you use your smartphone in order to enhance or augment your existing social relationships, and the unhealthiest outcomes are predicted when you use these technologies in ways that interfere with or replace said face-to-face connections,” Cavanagh said in an email interview.

Similarly, Sachs referenced a comedy sketch he’d seen about at-home dentistry, wherein patients might learn how to fill their own cavities. It’s one thing, he said, to learn to recognize signs you might need help from a trained professional. The same is true for mental health care.

“This is not something you really can do yourself,” he said.

Safety is a concern, too

When it comes to mental health advice shilled out on TikTok and other social media apps, safety can be a concern.

There’s the slightly more obvious aspect of that – taking misinformed advice from a stranger – but for young users, especially, there’s also a real risk of oversharing into a space where, as cliche as it sounds, no one is anonymous and digital footprints last virtually forever.

It’s not uncommon for a high-school-aged user to post a video lamenting their schoolmates had come across their account, hence gaining access to whatever vulnerable information they’d posted to their pages under a false assumption of anonymity.

At the end of the day, especially with people’s public accounts, it’s really impossible to know who is viewing your content, let alone saving it or sharing it.

“That’s where it’s important to start having these conversations as early as possible and in giving the kids the tools in order to have some understanding about what they’re putting out there and why that might be of a concern, that would be a risk for adolescents,” said Dr. Wynne Morgan, who works in the pediatric and adolescent psychiatry department UMass Memorial Health Care in Worcester.

Platforms like TikTok are certainly not negative across the board, however. They provide opportunities for people around the world to share their experiences, find commonalities, even commiserate about life’s challenges or indulge in self-deprecating jokes – to confirm they are not alone, and perhaps grow more comfortable talking about what has long been stigmatized and relegated to quiet, private conversations.

However, if care is needed, it’s the in-person (or telehealth) follow-through that makes the difference.

“I have seen this transformation in my own classrooms, where in recent years many students openly discuss their anxiety with me, for instance,” Cavanagh, from Assumption, said. “I would hope that this translates into them being more able to access services to help them.”