Matilde “Mattie” Castiel was 6 years old, unaccompanied except for her 8-year-old brother, when she left her native Cuba to come to the U.S.

Castiel was part of an American effort called Operation Peter Pan to get Cuban children out of a nation in upheaval during the early days of the Fidel Castro regime. Knowing no English, they first stayed with a foster family in Miami before moving to the Los Angeles area, where Castiel was later joined four months later by her parents.

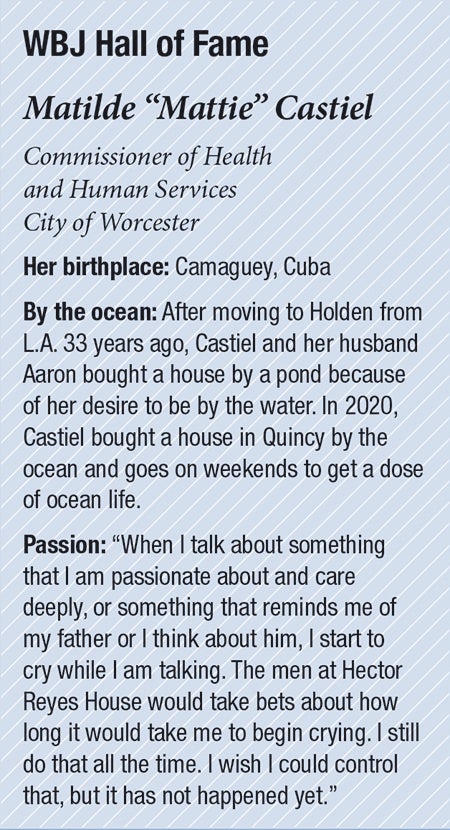

It’s an experience Castiel uses to this day to shape her work as Worcester’s health and human services commissioner, a position whose importance could hardly be any more important during a public health crisis that’s killed more than 400 Worcester residents.

To Castiel, the coronavirus pandemic has highlighted what she’s long known: not everyone receives the same quality healthcare, and not everyone has the same trust of government or the medical community. People of color have been especially hard hit by the pandemic, an acute problem exposing the issue Castiel has dedicated her career to: addressing healthcare inequity.

Those efforts have included speaking in her native Spanish at city press conferences to better get important messages to those who don’t understand English. Other times, she’s talked to groups about how she got vaccinated herself to demonstrate getting a shot is safe and effective. She enrolled in the Pfizer clinical trial at UMass Memorial Medical Center last year.

“There’s a lot of hesitancy about it,” Castiel said of the COVID-19 vaccine. “A lot of people say ‘Let me wait and see.’”

The pressing health crisis is new, but the work for Castiel isn’t.

“Part of what I’ve always wanted to do in my job is bring equity to the community,” said Castiel, who’s held the city’s top health position since 2015.

Before joining the city, Castiel was the executive director and medical director of the Latin American Health Alliance, a Worcester health clinic running the Hector Reyes House, a residential substance abuse treatment center. In that position in 2014, Castiel started Cafe Reyes, a Cuban restaurant on Shrewsbury Street serving as a training center for Hector Reyes House residents and graduates.

In fact, relatively little of what Castiel does could be seen as directly related to providing health care. Instead, she and her office focus much of their efforts on what are known as social determinants of health – the lack of nutritious food or access to reliable housing, for example, that might end up making it harder for someone to stay healthy or make doctor’s appointments. It includes helping formerly incarcerated people get their lives back on track or providing addiction treatment in correctional facilities.

More recently, that work has included vaccinating the city’s homeless and domestic violence shelter residents. Next up is public housing residents. Before the pandemic, Castiel and her office were often focused on the opioid epidemic, which kills dozens of Worcester residents a year and has only quietly slipped into the background during an even bigger health crisis.

“What we’ve always known is that it’s incredibly costly to not provide care to vulnerable populations,” Castiel said.

Castiel, who previously worked as a family physician, has seen such populations be disproportionately hit before. Early in her career she worked during the HIV crisis.

“Something that stays with you for a long time,” she said.

Castiel’s upbringing has stayed with her in a way helping her relate well to those she’s working to help. In 2018, she spoke at UMass Medical School in Worcester about her immigration story, along with Naheed Usmani, a professor of pediatrics at the school.

Castiel talked then about forging a path for herself often at odds with what her Jewish parents, who were born in Istanbul, had wanted for her.

“We were supposed to be dating and getting married and having kids, and I wasn’t doing any of that,” Castiel said.

She got emotional when talking about the often excruciating stories immigrants can tell, especially if they’ve fled persecution or war back home.

“When people come to this country, they come for a better life,” she said. “We may not have all the background, but they come here and they work and they do some amazing things.”

The project she was best known for before joining City Hall was creating Cafe Reyes and her work with the Hector Reyes House. Six years after she’s left, her legacy there is still strong.

“She always believed in me,” said Ricardo Juarbe, a cook at the cafe since 2016 and a Hector Reyes House resident. “Even my family turned their backs on me.”

Juarbe recalled relapsing once and making a 4 a.m. phone call to Castiel. She showed up – in her pajamas – to get him and get him help. He and others in the program often refer to her as a mother figure.

“She loves these guys,” said Jose Rivera, the operations director for the Hector Reyes House, where Castiel will still stop by every Tuesday to help provide medical services.

“You can see the difference when she’s there,” Rivera said of the brighter attitude program residents have when they see Castiel, someone who still regularly checks in with them. “She’s incredible. She’s like the energizer bunny.”

Cafe Reyes has been a critical part for program graduates to find discipline, purpose and support. It has meant so much to Edgardo Rentas, a cafe worker, he now splits his time between being a cook and being a case manager at the Hector Reyes House after getting certification.

Rentas was working as a barber and was passionate about that work, but said he wanted to work at Cafe Reyes and eventually become a case manager to help people recovering from addiction to give the same help he got.

“That’s why I’m still here,” he said.

Castiel always liked the idea of helping people, she said. Her mom was a homemaker, and her dad had only a third-grade education. In California, her mom worked folding towels and her dad stripped paint off furniture. A high school job as a pharmacy technician gave Castiel her first taste of a career in medicine, and she went for it.

After college in California, Castiel went to St. Louis for her medical residency program and met her husband. They decided to go to one area of the country, cold-weather New England, she initially sought to avoid – her mother said during Operation Peter Pan her daughter was allergic to the cold so that they’d end up someplace warm. Nonetheless, 33 years later, here they are.

“This is home,” Castiel said of Worcester.

During the pandemic, Castiel has seen hospitals and health agencies in her new home city work in a more collaborative way, giving her confidence that health inequities could be better addressed post-pandemic. Before, organizations didn’t need to work together as critically.

“We have a long way to go,” she said, “but we’ve come a long way.”