For the 48 Central Mass. breweries, the lockdowns changed consumer behavior with people now accustomed to consuming beers at home. The lack of taproom sales has forced breweries to close their doors.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

When Kevin Jarvi opened Milk Room Brewing Co. in 2019, little did he know his new small business would only open its doors twice before being thrust into the chaos of the COVID lockdowns.

Through quick adaptability and a rural outside business model, Milk Room not only survived its trial by fire, but the company is expanding with plans for a new taproom and disc golf course.

Jarvi attributes the brewery’s success to its beer pasture located on 30 acres at Alta Vista Farm in Rutland. The property made customers feel safe in an open, natural space and provided ample room for food trucks to meet the April 2020 food requirement signed by Gov. Charlie Baker, which stymied other breweries.

“Our whole business model ended up being driven by the COVID guidelines in the beginning,” Jarvi said.

Milk Room was one of the lucky ones. For the other 47 Central Massachusetts breweries, especially those in urban areas, the lockdowns changed consumer behavior with people now accustomed to buying craft beers in convenience stores or ordering beer to-go. The lack of subsequent taproom sales combined with inflation on necessary brewing supplies has forced breweries to close their doors.

The challenges ahead

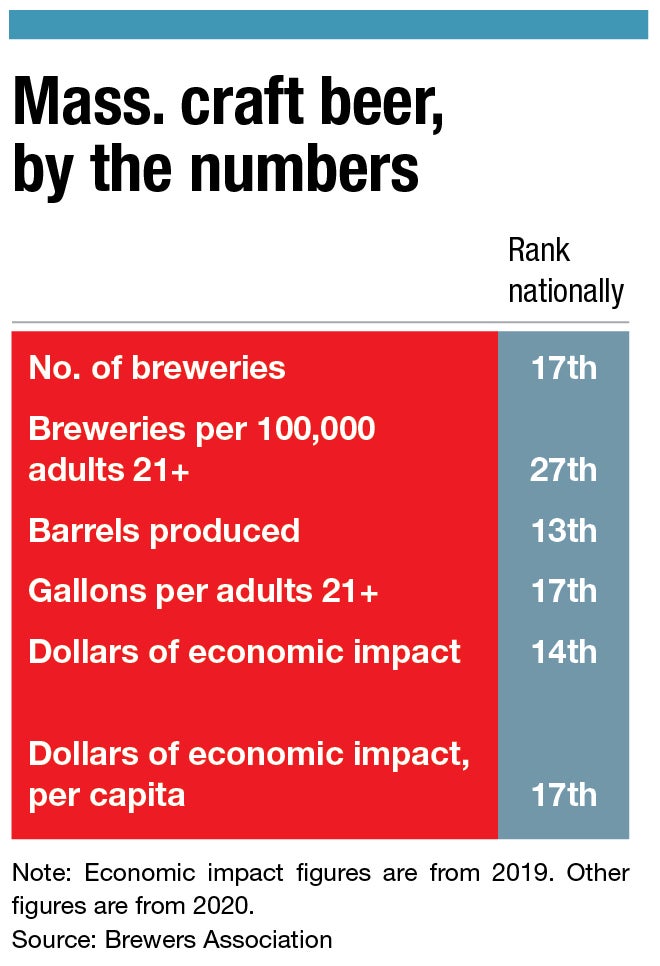

In 2021, 19 breweries throughout Massachusetts opened and 15 closed resulting in a statewide total of 214 breweries, according to Mass. Brew Bros., a blog working closely with the trade group Massachusetts Brewers Guild to analyze industry data. The net increase of four breweries is indicative of what those in the industry report seeing: slow but cautious recovery.

“That is a complicated answer, but breweries have fared very well,” said Katie Stinchon, executive director of Massachusetts Brewers Guild.

One major hurdle breweries face is a change in consumer behavior resulting from the lockdowns. More remote work means less office workers stopping into a pub or brewery for a beer after work. This particularly presents difficulties for urban locations who rely on work traffic to fill their taprooms, said Stinchon.

Taprooms are the lifeblood of the brewery industry, Stinchon said. While pubs and breweries offer to-go options or canned products, it is the margins of taproom sales that allow breweries to make money. During the canning process, overhead costs are spent on brewing, tin cans, canning, packaging, and distribution, while taproom sales are simply liquids in glasses.

Reducing overhead costs comes at a critical time for breweries as the prices of malt, tin for cans, and even cardboard for to-go containers escalate while supplies drop, said Stinchon.

The Omicron wave, the social trend of Dry January, and customers being weary of close inside spaces are all matters recovering breweries must contend with in the winter months.

“Spring can’t come fast enough. The warmth can’t come fast enough,” Stinchon said.

An optimistic outlook

Although admittedly overly optimistic about the national brewery industry, Bart Watson, chief economist for the national trade group Brewers Association, echoed Stinchon’s regional analysis.

“The biggest effect from COVID, at least in 2020, was where Americans drank. We generally drank about the same amount of beer, but we drink it in radically different places. We stopped going to bars and restaurants, and we started buying a lot more in convenience stores,” Watson said.

The hardships of 2020 were reflected in beer production, which nationally decreased by 9% that year, said Watson.

As COVID restrictions lessen and patrons start frequenting bars and breweries, the Brewers Association is seeing the tide turn. While 2021 numbers have yet to be finalized, Watson said most of the lost volume from 2020-2021 will be recouped in the coming year.

While there was no overarching reason why certain breweries survived and others closed, the industry is analyzing certain trends. Location and business model played big roles in viability. Facilities with pre-existing production quickly adapted and canned their products to meet the new demand of to-go purchases.

If 2020 was the year of the lockdowns, then 2022 will be the year of supply chain disruptions, said Watson.

“It costs more and takes longer to get almost anything these days, and there are a whole bunch of reasons for that,” he said.

Breweries face the difficult choice of either raising costs and risk losing customers, or taking the hit and reducing profit margins. Despite the obstacles, Watson is bullish on the industry’s future.

“My optimism is still based on the fact that there is clearly still strong consumer demand for flavorful, locally brewed beer. We have seen the brewery sales bounce back strongly, and for most breweries that is the most important financial engine for their business,” Watson said.

The Brewers Association is pushing for the replenishment of the Restaurant Revitalization Fund to provide federal assistance for bars, breweries, and restaurants.

Established under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, RRF was a $28.6-billion federal relief fund to help businesses stay open, but it closed in October after running out of money.

“The fund ran out of money with many people having applied but not getting any money, and we think: A) That is wrong because it picks winners and losers. Some people got money and others didn’t; and B) we just think that this is a program that is important to help the nation’s small hospitality businesses get back on their feet,” Watson said.

Breaking the mold

While nationally breweries were struggling to survive, Milk Room and the Rapscallion line of restaurants and pubs are opportunistically expanding.

Purchased by twin brothers Cedric and Peter Daniels in 2007, Rapscallion has grown to encompass Rapscallion Pub in Sturbridge, Rapscallion Brewery & Taproom in Spencer, Rapscallion Table & Tap in Acton, and Rapscallion Kitchen & Bar in Concord.

Founded on family values and a strong connection to community, Cedric and Peter believe in a slow and steady business plan. Oftentimes their thoughtful business choices were surpassed by more glamorous brewery startups investing in the latest trends, yet in the process gathered substantial debt. Meanwhile, Cedric said the company’s patient moves and focus on simply making quality beer enabled Rapscallion to survive the financial toll of the lockdowns. The lack of debt and multiple investors allowed them to quickly pivot as a team.

When COVID first struck, the Daniels family was determined not to layoff any workers in their four locations. Even when their regular staff could not fulfill their hospitality jobs due to lockdowns, the brothers still managed to keep employees on payroll by doing everything from upholdersting furniture and painting, to hand-pouring growler cans to fulfill to-go orders.

“That’s the beauty of this company; we are all very creative and adaptable,” Cedric said.

Rapscallion’s adaptability was repeatedly put to the test, he said. After being unable to meet the state-mandated food requirements for the pandemic at Rapscallion Pub, the management decided to temporarily close its Sturbridge location and renovate the two-level building to include a kitchen and lounge.

Rapscallion then refocused its efforts on creating a new production facility, Rapscallion Brewery & Taproom in Spencer, which enabled the company to shift to a package product model by offering cans, further expanding its operations.

During the peak of the pandemic, community members offered to give donations to Rapscallion and purposefully ordered more to-go meals to help them stay afloat. Cedric was so touched by the generosity of these customers he developed the Heritage Club, a lifetime Rapscallion mug club membership, to give to them in return.

Cedric said breweries with a strong foundation, a sense of identity, and rich community ties will be able to overcome industry challenges better than establishments focused on the bottom line.

“You have to be true to who you are. You cannot be that trendy, flash-in-the-pan brewery; otherwise you won’t survive. Why grow for the sake of growing if you are not going to help the community that helped get you where you are?” Cedric said.