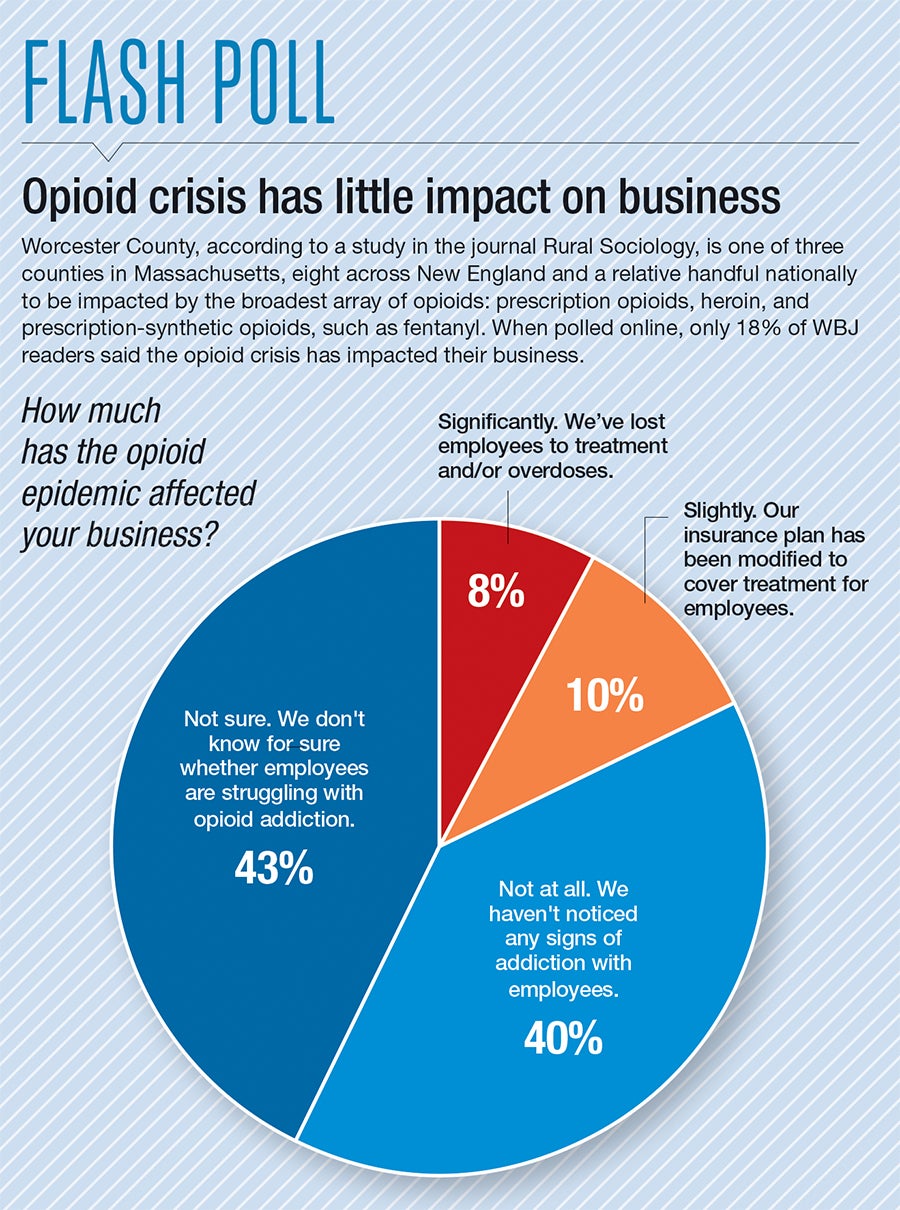

Worcester county is one of three counties in Massachusetts and eight across New England to be hit by the broadest array of opioids: prescription opioids, heroin, and prescription–synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

First came a wave of prescription opioids, hitting Worcester County by the tens of millions leading up to a deadly epidemic sweeping locally and across the country.

Heroin became widespread next. The street drug was found in more than two thirds of opioid-related deaths across the state in 2014 and 2015, just as opioid deaths were about to peak, according to Massachusetts Department of Public Health data.

Then came fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 times more potent than heroin. Lately, it’s been found in 90% or more of opioid deaths in Massachusetts.

Health officials have had a challenge meeting any one of these three opioid classifications. In Worcester County, though, that task is especially daunting.

The county is one of three counties in Massachusetts and eight across New England to be hit by the broadest array of opioids: prescription opioids, heroin, and prescription–synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl.

These findings, published in the journal Rural Sociology, shows how wide-ranging the opioid epidemic has become in places like Worcester County. Data has shown prescription opioids flooded into cities like Worcester, Gardner and Athol in the years leading up to a spike in opioid-related deaths, and since then, the number of overdose deaths including fentanyl has soared.

With such strong opioids in patients’ systems, health providers now have a more complicated task in treating those who’ve overdosed.

“Often, one dose of Narcan is not enough,” said Dr. Melissa Buchner-Mehling, the medical director of advisory services at Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester, referring to the brand of an overdose antidote.

Rare company

Only a tiny share of more than 3,000 counties nationally hit what researchers called a syndemic, meaning it suffered from epidemics of all three types of opioid crises.

In Massachusetts, Worcester County was joined by Hampden County, which includes Springfield, and Berkshire County on the New York border. Only five other counties in New England made the syndemic distinction, all in Connecticut, including Windham County, which is part of the Worcester metropolitan area.

Connecticut – which had only three counties not included in the worst category – isn’t the only state hit so hard by all three opioid challenges. So, too, is Maryland, with 12 of its 20 counties put by the Rural Sociology study into the category of a syndemic.

Most of the other counties determined to have a syndemic are scattered in states known to have major opioid issues including West Virginia and Kentucky, along with western Pennsylvania and remote parts of New Mexico. But much of those states’ counties aren’t in Worcester County’s category. Only about 15% of Kentucky’s counties hit that threshold, only about a third of Ohio’s, and around one-fourth of West Virginia’s.

Researchers from Iowa State University, Syracuse University and the University of Iowa used U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention overdose rates starting in 2004 to compile their study.

“We find that prescription–related epidemic counties, whether rural or urban, have been ‘left behind’ the rest of the nation,” the researchers wrote.

“These communities are less populated and more remote, older and mostly white, have a history of drug abuse, and are former farm and factory communities that have been in decline since the 1990s. Overdoses in these places exemplify the ‘deaths of despair’ narrative.

“By contrast,” they added, “heroin and opioid syndemic counties tend to be more urban, connected to interstates, ethnically diverse, and in general more economically secure. The urban opioid crisis follows the path of previous drug epidemics, affecting a disadvantaged subpopulation that has been left behind rather than the entire community.”

At Harrington Hospital in Southbridge, Gregory Mirhej sees another factor, as well: Heroin has become too common and too affordable.

“There’s still a fairly large number of patients who can say this started back with a sports injury, and they were prescribed something; and things just progressed over time. That’s still true. I think it’s getting less true over time,” said Mirhej, the hospital’s vice president for behavioral health services.

Now, he said, street drugs have moved to the forefront.

“It’s just so ubiquitous,” Mirhej said of heroin. “It’s around in a way that it never was before. It’s accessible, and it’s cheap. That’s taken the stigma away, too.”

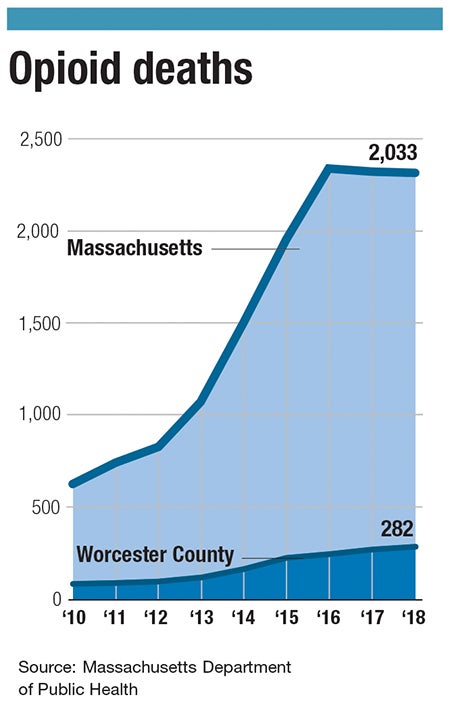

Responding to worsening numbers

Opioid-related deaths in Worcester County have spiked this decade, from 79 in 2010 to 282 in 2018, according to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. The county has a slightly disproportionate share of the state’s opioid deaths, accounting for more than 14% of its overdoses but 12% of its population.

At UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester, fentanyl has been found in more than 90% of overdoses. That includes patients who wrongly believed they were snorting prescription opioids, said Dr. Kavita Babu, a toxicologist and the hospital’s chief opioid officer.

Fentanyl has been so common, Babu said, health providers have been finding less and less heroin.

“Many of our opioid users tell us that fentanyl is the only drug out there, and finding heroin is increasingly difficult,” she said.

Opioid deaths have been down through the first three-quarters of 2019 in Massachusetts, according to the state Department of Public Health. The year-to-year decrease was 6%, with 1,460 opioid-related deaths either confirmed or estimated.

But fentanyl was present in a higher proportion of cases than before: 93% of cases where a toxicology screen was done, the state said. Synthetic opioids as a whole accounted for 24.5% of Massachusetts overdose deaths of any kind in 2017, according to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports.

The national average that year was just 9%, with Massachusetts placing sixth highest.

Prescription opioids, meanwhile, were present in 13% of opioid fatalities in Massachusetts in the first three-quarters of 2019, illustrating how much less pills such as OxyContin are directly responsible for deaths this far into the epidemic.

Statewide, the number of confirmed or suspected opioid deaths peaked at 2,095 in 2016. By last year, that number fell 3% to 2,033.

Health officials in Worcester are taking a broad range of actions to reflect the types of opioid cases they’re seeing.

At the Family Health Center of Worcester, the effort includes looking beyond a patient’s addiction to include previous trauma helping to explain what led to the addiction, said CEO Lou Brady. At UMass Memorial, the hospital offers medication disposal programs, distribution programs for bystanders to administer overdose antidotes, and easy access to medication for addiction treatment, such as methadone.

At Saint Vincent, the response includes prescribing acetaminophen instead of opioid painkillers for patients. The number of staffers given access to Narcan to respond to an overdose has been increased.

The efforts so far haven’t been enough.

“I have not seen a corner turn yet. I’ve yet to,” Buchner-Mehling said. “That’s my hope for the future. It’s going to take the entire community to turn that corner.”