Conquering cancer in Central Mass., one patient at a time

In 1971, President Richard Nixon declared a “war on cancer.” But despite plenty of research on the disease since then, progress on reducing deaths related to the disease has been frustratingly slow. Now, scientists and doctors have opened a new front in the war: personalized medicine.

"I think we've understood to some extent that cancer's not one particular disease but a collection of different types of diseases," said Joseph Duffy, head of Worcester Polytechnic Institute's biology and biotechnology department. "The biologies of tumors differ significantly."

The push toward personalized medicine involves a lot of moving parts: tumor biopsies shuttled from bedside to lab, fruit flies, mice and, of course, the constant search for funding. And Central Massachusetts institutions and companies are right in the middle of it.

Duffy studies a family of receptor molecules tied to some types of breast, lung and colon cancers. Working with fruit flies, he helped discover a protein molecule that could bind to the receptors, inhibiting the out-of-control growth that is cancer. While further tests found human receptors didn't respond the same way, Duffy and his colleagues are doing more work to modify the protein or find a replacement that would work on people.

Once the biochemistry puzzle is solved, Duffy said, there's still a long road to creating a new class of drugs for personalized medicine. So far, his research has been funded mainly through the National Science Foundation. He said the next big step could involve a partnership with a pharmaceutical company, but companies these days are often demanding a therapy be well along the road to development before they're willing to take it on. That might mean the lab will need to get as far as modeling its therapies in mice before it can find a company willing to take a risk on them.

Other researchers are looking at different pieces of the puzzle. Another team of researchers at WPI led by Patrick Flaherty, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering, has developed a big-data tool to allow for more accurate biopsy results. Instead of determining just the dominant type of cancer cell in a tumor, the statistical model can identify multiple subtypes that often exist within a single tumor. That means more opportunities to determine exactly what type of treatment is appropriate for a given patient.

Meanwhile, Worcester-based Nemucore Medical Innovations Inc. is developing therapies that target ovarian, uterine and breast cancers. CEO Timothy Coleman said each drug it's working on goes with a diagnostic technology that can determine whether it's appropriate for any given patient.

“When we look a patient population, we really want to stratify them into patients that are going to be responders versus those that are not going to be,” he said. It's best to know ahead of time, to avoid exposing patients to treatments that won't work and have toxic side-effects.

Nemucore has one promising molecular therapy set to start a second-phase trial and two others that will be in initial-phase trials over the next year.

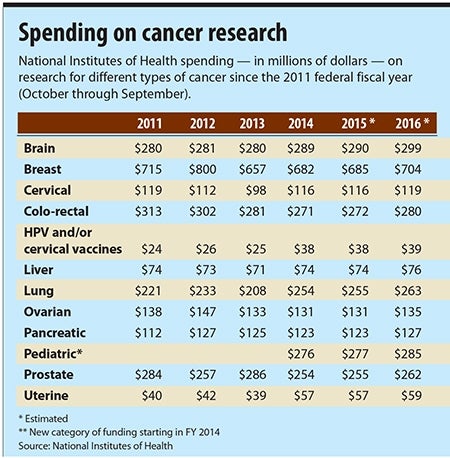

Like Duffy's work at WPI, Nemucore's drug development so far has been funded largely with government money, from the National Institutes of Health, as well as foundation dollars. Now, though, Coleman said, the company is bringing on investors, and it aims to go public in 12 to 15 months.

UMass research drawing interest

At the University of Massachusetts Medical School, molecular biologist Dale Greiner and Giles Whalen, director of the Cancer Center of Excellence, are taking a different tack in pursuing personalized cancer treatments. Together, they helped found the multi-campus UMass Cancer Avatar Institute, which is developing mice that can act as “avatars” of specific cancer patients, with immune systems and tumors engineered to mirror a patient's specific situation.

Greiner said that, within a couple of years, their technology may allow a doctor to send a patient's tumor sample to a lab and have potential therapies tested on 100 avatar mice before starting treatment for the real patient.

Already, the institute is using the mouse models to grow tumors taken from patient biopsies, letting researchers study specific types of cancer. Greiner said this is the result of a complex collaboration among clinical oncologists and basic researchers. Patients sign universal consent forms allowing for their biopsy samples to be used in research. A tumor bank assigns numbers to the samples to protect patient privacy, and the researchers tailor their mice for colleagues' use.

“This is starting to get a lot of attention from pharmaceuticals,” Greiner said. “What they are looking for (are) ways to test drugs in development pre-clinically on patient tumors … so we are now talking to and actually working with some companies, major players in cancer drug development.”

That's just one more layer in the complex web of relationships that is moving personalized cancer research forward in Central Massachusetts and elsewhere.

0 Comments