According to federal statistics, fewer than half of the students in the United States who start college end up graduating. That’s a problem, according to some education officials. But many in the field, and in Central Massachusetts, are calling for the way graduation rates are measured by the federal government to be changed.

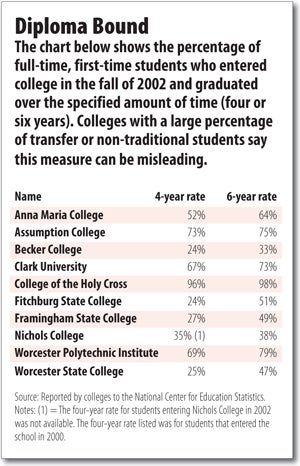

Among the bachelor’s degree granting colleges in the Worcester area, the percentage of students that graduate within four years ranges from 24 percent (Becker College and Fitchburg State) to 96 percent (Holy Cross), according to the most recent statistics from the National Center for Education Statistics. The rates are for students who entered college in the fall of 2002.

Behind The Statistics

While college officials say graduation rates can be misleading due to the type of student population that attends a given school, the rates are an increasingly important issue for parents. As a result, local schools are monitoring their rates closely and taking steps to ensure more students leave their campuses with degrees.

The graduation rates compiled by the federal government measure the progress of first-year, full-time students who enter school in the fall and graduate from the same institution. Transfer students are usually not taken into account. Because state schools in particular see a lot of transfer students — at Framingham State, it’s about 30 percent this year — the graduation rates for these schools can look artificially low.

“It’s the most misunderstood outcome measure in higher education,” said Timothy Flanagan, president of Framingham State College, where the reported four-year graduation rate is 27 percent. “There are a lot of intricacies and nuances, it’s easily manipulated, and it doesn’t really measure the right thing — it’s a classic traditional measure of productivity that doesn’t accurately measure the value added.”

In addition to not counting transfer students, the fed’s definition of graduation rate is restricted to freshmen who graduate within 150 percent of the standard time. Students who take longer than six years are not counted by the federal statistics, even if they do graduate.

This skews the data for any school that has a lot of low-income students, older students, or other “non-traditional” students (such as working moms), because these students often take extra time to get their degrees, largely because they have to hold down a job while studying. This is another reason the graduation rate looks lower than it actually is for state schools, and for private schools like Becker that have a large chunk of older, working students.

It’s a significant point, because non-traditional students are now in the majority. Patricia McGuire, president of Trinity Washington University in Washington, D.C., is an expert on the issue who would like to see the tracking statistics improved.

McGuire said “students who live on campus, get a degree in four years, and have college paid for by their parents, are only about 20 percent of the population. But these are the students everyone has in mind when they make public-policy decisions.”

Guiding Students

Imperfect as the statistics are, schools take graduation rates seriously, and are doing a lot to work on the problem.

“There is abundant evidence that there are things we can do to improve graduation rates,” Flanagan said.

Since the number one reason students drop out is lack of funds, schools work to provide as much financial aid as possible. It’s a challenge for most schools, because the mix of aid has changed — the percentage of aid in the form of grants is far lower than it once was, and the percentage of loans is far higher. This is another reason more and more students work while attending school.

So one way schools help students is to accommodate this need to work. Framingham State tries hard to identify on-campus jobs for students, and has a career services office that helps locate jobs in the area. There is even help with transportation — working with Tommy’s Taxi of Framingham, the school created a taxi voucher system. Working students can purchase five vouchers for $20, so any ride to or from a job costs the student only $4.

At Holy Cross, which has the highest graduation rate in the area and one of the highest graduation rates in the entire country, the opposite approach is taken — an aggressive approach to financial aid for those who need it.

“We have a two part policy for financial aid,” said Timothy Austin, vice president of academic affairs and dean of Holy Cross. “The first part is that we do not consider finance at all when deciding whether to admit students. After a student is admitted, we make the finances work — there may be a loan component, there may be work study, but no student should have to drop out because of financial issues.”

Holy Cross also requires eight semesters in residence.

“No matter how many courses you have,” Austin said, “there is no such thing as early graduation. We feel that graduation is not just a matter of getting enough credits but rather a process of maturing through four years.”

Another thing that helps graduation rates is paying close attention to the students.

“From the chaplain to the residence [people] to the advisors to the faculty,” said Austin, “we all take an intense interest in each student. That’s much harder to do when you’re not a residential college.”

Clark University, which has a reported four-year graduation rate of 67 percent, also keeps a keen eye out for trouble.

“We are very student-centered at Clark,” said Denise Darrigrand, dean of students at Clark. “We work with them individually as much as possible, and try to anticipate issues.”

All of the schools the Worcester Business Journal spoke with made a similar point.

As Michael Shanley, executive assistant to the president for external affairs at Fitchburg State, puts it, “We use the faculty as an early warning system.”

Local schools are also working to make life easier for transfer students. A state transfer agreement among state colleges and community colleges synchs up general education requirements between the two types of schools, making the transition easier for students.

Another strategy is to create “articulation agreements” between schools. Faculty members at Framingham State meet directly with faculty in the same field at the three community colleges from which Framingham gets the most transfer students—Mass Bay, Quinsigamond, and Middlesex.