It was launched to fill a void.

Budget troubles in the mid-2000s forced Medway High School to cut many of its electives, leaving many students with multiple study halls each day.

And the new high school — which opened in 2003 — had enough unoccupied space to support additional programs.

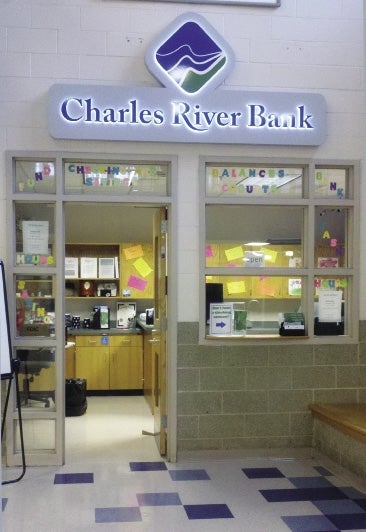

So in 2006, Charles River Bank of Medway opened its first in-school bank branch, kicking off a second wave of high school bank branch construction across Central Massachusetts in recent years.

Today, more than 30 Medway High students apply each year for one of 15 slots in the school’s banking program, which includes both a financial education component and working behind the counter as a teller, said Ann Sherry, the bank’s senior vice president of customer care and relationship development.

Participating students also have the chance to get paid by filling in at traditional Charles River branches on Thursday nights, Saturdays or when regular employees take vacation.

And one day, she said, they might be able parlay that experience into permanent positions with the bank, like current members of Charles River’s marketing and mortgage consultant teams.

“It’s been very good for both sides,” Sherry said.

At least eight locally-based banks and credit unions operate some 12 branches inside Central Massachusetts high schools, nearly all of which opened in the late 1980s to early 1990s, or since 2006.

High school branches can typically be accessed only by students and staff during part of each school day. Still, students are seeing more than just nominal deposits and withdrawals.

Medway High has its own students manage the school’s cafeteria and student activities accounts, Sherry said, while the food services division at Tahanto Regional Middle-High School in Boylston does all its banking through the on-site Clinton Savings Bank, said Ben Milliner, the school’s assistant principal.

Central One Federal Credit Union’s branches at Shrewsbury and Westborough high schools see 90 percent of the same transactions as a traditional branch, President and CEO David L’Ecuyer said. The only requests students are unlikely to see are those involving international currency or other complex matters, he added.

Bank leaders see the branches as a way to give back to the community and cultivate bonds with millennials.

“These are our future members,” said Carol Southworth, a senior vice president at Leominster Credit Union. “These are the people that are eventually going to have a car loan or a mortgage.”

Leominster Credit Union has operated branches since the 1980s inside Clinton High School and Wachusett Regional High School in Holden, Southworth said. Other local financial institutions with a high school presence include Worcester-based Bay State Savings Bank, Dean Bank of Franklin, Worcester Credit Union and Workers’ Credit Union of Fitchburg.

But in other parts of the country, it’s no longer only community banks that are participating.

Bank holding giant Capital One opened its first in-school branch in the Bronx in 2008, said Barry Wides, deputy comptroller of community affairs for the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), while Union Bank — a large lender with retail branches all over the West Coast — has student-run branches in three low-income, high-immigrant California neighborhoods.

“My sense is that they are increasing, in part because banks want to be more involved in financial education,” Wides said.

States with smaller school districts, like Massachusetts, are more likely to try out initiatives such as in-school bank branches than larger, county-run school districts, which are pervasive in other parts of the country, Wides said.

Boosting teens’ financial IQ

And a recent study documented the benefits of in-school bank branches and financial education at the elementary school level. The U.S. Department of the Treasury found that participating students improved by an average of two points on a 13-point financial knowledge assessment after five hours of classroom-based financial education and access to an in-school bank or credit union branch.

There is little to be gained financially, however, from operating an in-school branch, bank leaders emphasized.

“Everybody needs to be honest with themselves that it’s not a moneymaker, it’s not high-volume,” L’Ecuyer said. “It’s a service for students.”