Small businesses run by people of color struggle to find financing as VCs' priorities have shifted away from providing multicultural opportunities

Photo | EDD COTE

After closing down her store in the Worcester Public Market, Katherine Aguilar runs all operations for Kommon Sense Co. from her home studio.

Photo | EDD COTE

After closing down her store in the Worcester Public Market, Katherine Aguilar runs all operations for Kommon Sense Co. from her home studio.

When Katherine Aguilar started her business with $300 on an ex-boyfriend’s credit card, she did not have a plan for how she would sustainably fund her endeavor to open the first plastic-free gift shop in Worcester. Now four years later, financing the growth of Kommon Sense Co., which specializes in locally and ethically sourced gifts while educating consumers about reducing their carbon footprints, has been a trial-and-error process.

“It would be nice if we had a roadmap or a guide for how to do this,” said Aguilar.

Aguilar is not alone on the confusing road to financing a small business, made more winding for business owners of color who remain disadvantaged in the world of large loans and venture capital, despite increased awareness of inequities. Small grants have been enough for Aguilar’s tiny team, made up of herself and two seasonal employees, but other startups seeking out larger investments have come up short, in large part because the deck is stacked against them.

Betty Francisco, CEO of Boston Impact Initiative, a nonprofit investment fund focused on economic and racial justice, is one voice in the state bringing awareness and making strides to address the gaps causing minority startup entrepreneurs to have less access to capital. Francisco began her career as a corporate lawyer focused on deals related to transactions. In the eight years she worked in that role, she saw what she called a significant lack of representation among investor firms.

“I didn’t see people who look like me,” she said.

While Francisco watched opportunities appear for entrepreneurs, few were focused on people of color. She shifted careers to her role now at BII, where she channels her passion for helping women- and person-of-color-owned businesses. The BII pilot fund, which only focused on Boston-based and Eastern Massachusetts businesses, is expanding, now on its third and largest financing round yet.

Francisco said the next available round of funding, amounting to $20 million, will be available with a focus on immigrant populations outside of Boston growing and starting businesses. In Worcester, the fund is looking to build relationships with Latino-owned businesses.

Francisco credits COVID-era grants as helping small businesses stay afloat and manage their expenses.

“But they only did just so much,” she said. “There is a need for much more money to stabilize and grow.”

Reduced priority on multiculturalism

Shawna Curran, founder and CEO of STEM ENRG, a Worcester company running a cohort-based training program teaching coding, project management, and financial literacy for women of color, has acutely felt the pandemic-era grants and loans were not enough. Since Curran’s business was not solidly established before the pandemic, the recovery funds did not apply to her, and finding funding now has been an uphill battle.

Curran has conducted her first two cohorts without any external funding for her business and said with her third cohort she is hoping to gain enough revenue traction to be eligible for financing STEM ENRG has been too narrow for thus far.

“There are customers out there willing to pay and a need and a desire for this program,” said Curran, citing the hundreds of applications she has received for 20 slots in the cohort. “The challenge is finding operating capital to invest in things to get to the next level.”

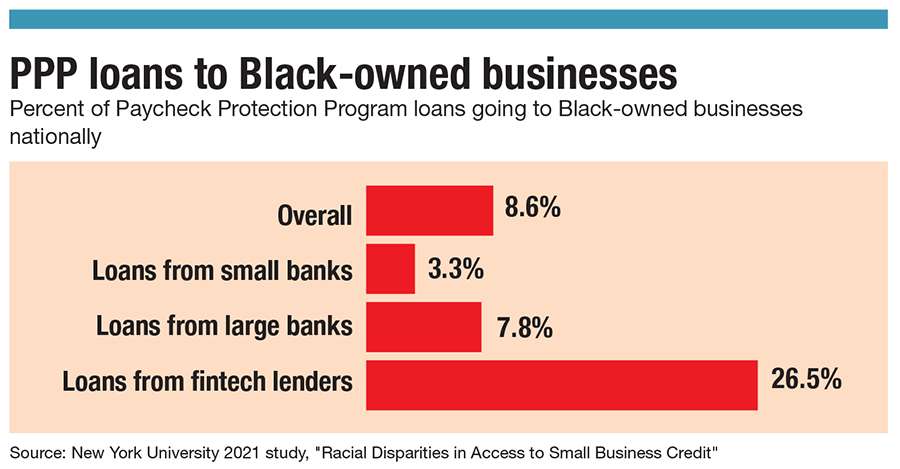

The racial reckoning in the U.S. begun in 2020 spurred businesses across the country to make commitments to diversity and inclusion. For investment firms, this came in the form of promises to be more equitable in financing business owned by minority groups. Yet much of that fervor has reverted to pre-2020 levels, according to Morgan Stanley’s 2022 report “Social Equity and Funding Gaps.” In 2020, 43% of VCs said finding opportunities with multicultural-founded companies was a top priority for their firm. In 2022, that number fell to 32%.

This is noticeable on the ground, said Francisco.

“We need to figure out how we can actually realign those strategic promises,” she said.

Dianne Austin, CEO and co-founder of Boston-based Coils to Locs, runs a wig company for cancer patients who, like Austin when she was undergoing treatment, want wigs in the same style as their natural very curly hair. Austin found herself unable to find the quality wigs in her hair type available for patients with straight hair.

Austin said she has faced systemic barriers in getting the kind of financing she has hoped for. While she has had success in accelerators for BIPOC (Black, indigenous people of color) business owners and received grants specifically for businesses owned by people of color, they have largely been small grants. When she applied to a high-profile Boston accelerator, she said she received feedback from a judge upon rejection saying the data she provided about the need for her products wasn’t believable.

“That kind of thinking prevents you from getting into programs that could give you access to much needed funding,” said Austin.

Looking for the money

Traditional business acumen suggests founders start with a friends-and-family financing round, where startup founders raise money from their personal networks. This round is more challenging for marginalized groups as they historically have not had the same level of financial security, said Austin.

“For systemic reasons, it's not a level playing field,” she said. “There is systemic racism even as it relates to friends and family rounds if they have less money to invest.”

Seeking funding from firms that can’t relate to the need for her product has been a challenge, too, said Austin.

“You can have all your ducks in a row, but if there's a lack of understanding of why it's important due to lack of relatability, it's a difficult leap,” she said.

The numbers are not in Austin’s favor as a Black business starter. According to Morgan Stanley, Black-owned businesses are three times more likely to be rejected for funding as compared to white-owned businesses; additionally, 61% of businesses started by Black women are self-funded. This trend continues despite the fact that Black women are the fastest growing demographic of entrepreneurs in the U.S., according to Morgan Stanley.

Beyond funding from venture capital firms and specifically tailored grants, commercial loans from local banks remain an option.

At Auburn-based bank Webster Five, helping new businesses get started is a priority. When Christopher Watson, senior vice president and senior lending officer in business banking, started at the bank 5.5 years ago, a priority was to get preferred status with the U.S. Small Business Administration, which allows the bank more flexibility in approving loans for newly established businesses.

“We are a community bank. We are here to support local businesses, and as a preferred lender, we get to make that decision,” said Watson.

Still, the bank doesn’t have a method to track demographics for who is receiving loans, said Watson, though he said Webster Five offers the same loan products across the board, without specific programs for women-owned or BIPOC-owned businesses.

As a safeguard for equity, no one person working at the bank is able to turn down a loan request without cosigning from another banker, Watson said.

But even getting loan approval can be a challenge when starting up a business. For Curran, loan processes have not panned out as she hoped.

“Being a business owner and pulling myself up by my bootstraps, my credit is not as good as it was when I was working a 9-5,” said Curran.

For Aguilar, pursuing loans as a means of financing Kommon Sense Co. has not been as desirable as grant funding. A small handful of $5,000-$10,000 grants sustained Aguilar and the shop through the pandemic, during which she was hesitant to apply for government loans, such as the Paycheck Protection Program. The applications have been unnecessarily confusing and specific, said Aguilar.

Aguilar has been running her shop out of a location in the Worcester Public Market in the Canal District, but she ended up closing down the storefront. Kommon Sense Co. now runs out of a small space in her home.

Curran is still hopeful the funding she needs to take the next leap with STEM ENRG is on the horizon.

“I know it's there. It's right there. But how do I get it?” she said.

0 Comments