Colleges in New England were already on the lookout for an expected drop in high school-age graduates locally, and struggling in some cases to balance high costs with keeping education affordable for students.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Colleges in New England were already on the lookout for an expected drop in high school-age graduates locally, and struggling in some cases to balance high costs with keeping education affordable for students.

Then the coronavirus pandemic hit.

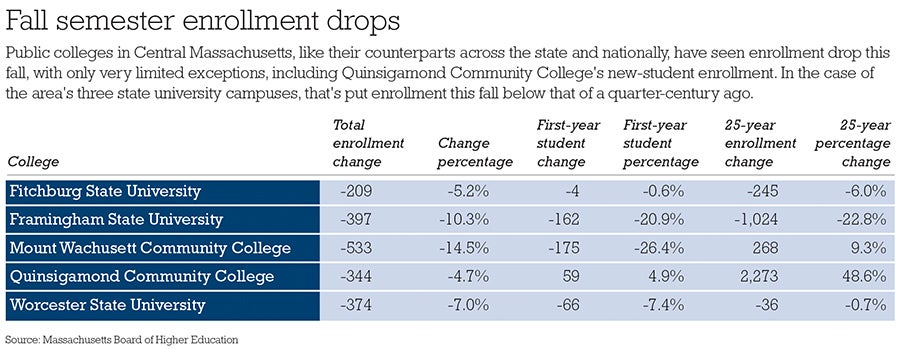

Enrollment at public colleges in Central Massachusetts has dropped substantially this fall, including by more than 10% at Framingham State University and Mount Wachusett Community College, a trend echoed statewide as higher education has been upended by the coronavirus pandemic.

At Mount Wachusett in Gardner, enrollment this fall is down an estimated nearly 15% from the prior year, according to the Massachusetts Board of Higher Education. At Framingham State, the drop was 10%. At Worcester State University, it was 7%.

Statewide, from community colleges to the University of Massachusetts, enrollment this fall dropped by 7.1%.

“There have been declines all over the map, and for larger and smaller institutions,” Jonathan Keller, the state's senior associate commissioner for research and planning, said at a Board of Higher Education meeting in October.

A concern among state education officials, Keller said, is the enrollment drops could be more than a short-term blip attributable to the pandemic. There is a fear, he said, students who aren't enrolling in college this fall may not in the future, either.

Pandemic-related factors most often cited by students have included personal finances for students, frustration with a lack of campus life, dissatisfaction with distance learning, and increases in child care and parenting responsibilities, Keller said.

Public colleges in Central Massachusetts went at least partially online this fall because of the pandemic.

State university campuses in Framingham, Fitchburg and Worcester held classes in a hybrid in-person and online format, with decreased capacity in dorms and mandated testing on campus. Mount Wachusett and Worcester’s Quinsigamond Community College, which don’t have dorms, have held few courses on campus.

Adjusting to unpredictable times

During the Great Recession, community college enrollment generally skyrocketed – but that hasn’t happened this time, at least not yet.

“I’m not surprised by anything anymore this year,” said James Vander Hooven, the Mount Wachusett president.

Vander Hooven understands why so many students have chosen not to enroll. Many Mount Wachusett students also balance work and family obligations, and school rightfully comes behind those when people prioritize their needs, he said.

“I have confidence that as we get through this crisis, we can be that resource for them again,” Vander Hooven said.

He knows community colleges will be counted on once the economy’s back to normal.

“The state, for its economic survival and revival, must rely on the resources and community colleges provide for jobs in our regions,” Vander Hooven said.

Framingham State expected a big drop in students this fall. In fact, it predicted a 12% drop, and ended up at about 10%.

Now, President Javier Cevallos said, the university will work toward getting many of those students back. Some have deferred their enrollment by a year, but many others may have decided to indefinitely postpone college because of family or work obligations.

Framingham State’s student body is traditionally 40% Pell grant recipients – those who demonstrate a financial need – and nearly half first-generation college students. Cevallos is among those who are concerned those students may never enroll, their career plans thrown off course forever because of the pandemic.

“Those are the populations we need to support,” Cevallos said.

Like at Framingham State, enrollment this fall has fallen the most among first-year students, indicating general enrollment drops were likely attributable to students choosing not to begin their college careers rather than existing students not returning.

Framingham State's freshman enrollment dropped this fall by 21%. The school is near its lowest enrollment at any point in the past quarter century, according to the state data.

At Mount Wachusett, first-year enrollment this fall is down 26%. A few exceptions to first-year declines exist, most notably at Worcester's Quinsigamond Community College, where freshman enrollment grew by 5%.

Student numbers were already trending downward in Massachusetts before this fall. Among all state schools, enrollment is now down for seven straight years. UMass enrollment, which did not include the medical school in Worcester, is roughly flat this fall.

Enrollment has been down this fall nationally, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

First-year enrollment nationally is down 16% and total undergraduate enrollment is down 4%. Enrollment is down twice as much – 8% – this fall for students who receive Pell grants, according to the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, indicating a potentially especially notable effect on lower-income students who may need a college education the most to get ahead economically.

The NAICU study found 57% of colleges nationally reported a drop in enrollment this fall.

Less revenue and more costs

Revenue is on a sharp decline nationally. In June, the American Council on Education estimated revenue loss this school year of $23 billion thanks to fewer students enrolling.

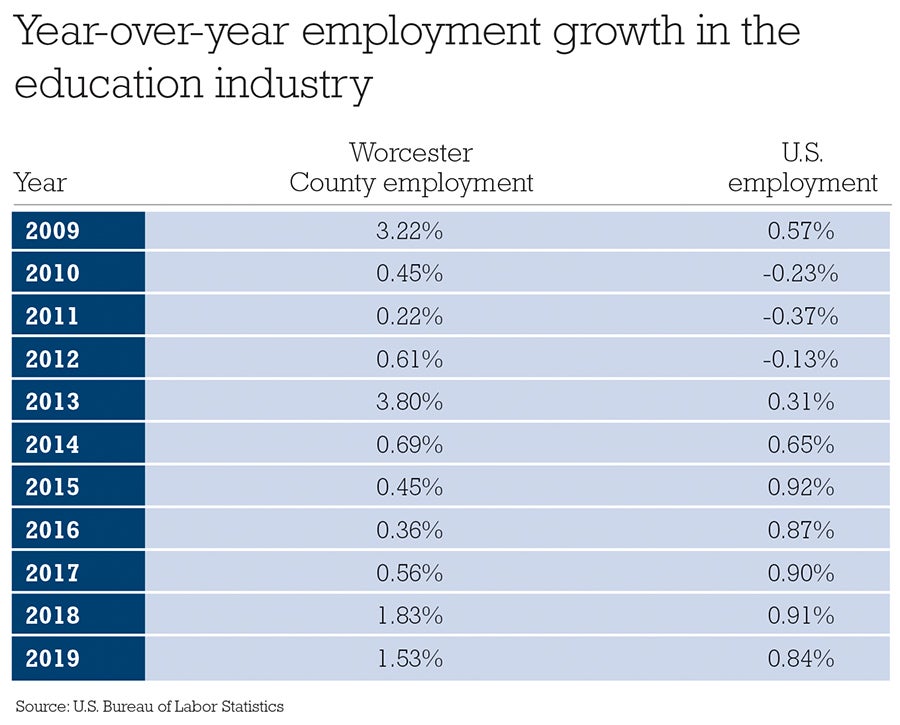

Colleges have cut a combined 337,000 workers since before the pandemic, according to Robert Kelchen, a higher education expert at Seton Hall University in New Jersey. Most of those appear to be temporary, Kelchen wrote in the Chronicle of Higher Education in October, but some signs show colleges are taking aggressive steps to significantly pare their faculty ranks.

Cost-cutting efforts should prevent widespread college closures, Kelchen said.

“But the next several years will still be painful ones for higher education,” he said.

That’s a struggle being felt on public campuses in Central Massachusetts, where fewer students have meant lower revenue levels, and a state budgetary crisis has brought an expectation for less state aid. In fact, budgetary challenges started in earnest back in the spring semester, when many campuses refunded room-and-board charges once they sent students home early, while spending to upgrade classroom technology and improve sanitation practices.

Those fiscal problems have only worsened.

The state’s nine state university campuses have seen nearly $25 million in revenue drop, and more than $11 million drop in state aid this school year, according to EY-Parthenon, a Boston consulting firm working with the Board of Higher Education.

Those losses are being offset by more than $39 million in debt restructuring, $14 million more in higher-than-expected tuition and fee revenue, and more than $9 million in cost savings. That leaves a gap of nearly $18 million among the nine universities whose budgets total more than $800 million.

Three of the nine state universities – which ones specifically aren’t being disclosed – are at risk of falling below a threshold this school year for having enough cash on hand for six months of operations expenses. Still, each is relatively financially healthy thanks to budget cuts, said Haven Ladd, a managing director at EY-Parthenon.

Framingham State has been able to avoid layoffs but has a $1-million structural deficit it plans to close through attrition, Cevallos said.

At Worcester State, President Barry Maloney said he expects budgetary challenges related to the pandemic to last at least through the fall 2021 semester. That’s spurred his administration to more closely scrutinize oversight of operations during the pandemic, he said.

Maloney pointed to one positive change that came from the pandemic: a forced quick change toward more extensive use of technology in classrooms, a process that otherwise could have taken years.

“That’s something we all need to be mindful of,” Maloney said.

At the state’s 15 community colleges, the picture is similarly challenging. Those campuses have instituted a total of $20 million in cost savings to partially offset an expected loss of state aid of nearly $30 million and a revenue loss of $5 million. Between those campuses – whose budgets total more than $700 million – a budget gap of more than $6 million remains.

Mount Wachusett has avoided layoffs in part thanks to a larger financial reserve, Vander Hooven said.

The five public campuses in Central Massachusetts, not counting UMass Medical School in Worcester, received a combined $29 million in federal aid under the $2-trillion CARES Act, with much of it earmarked for student aid. Congress hasn’t approved subsequent aid under other potential legislation.

To Chris Gabrieli, the Board of Higher Education chairman, campuses appear to be working proactively enough to manage their budgets during such an unpredictable time.

“Our campuses are, I think, are positioned as well as they can be, through the adjustments they’ve made and the approaches they’re taking, to be fiscally solid through this year,” Gabrieli said.