Strained nonprofits are finding coronavirus pandemic is becoming a poor person’s crisis

PHOTO/MATT WRIGHT

Mike Hyland, the president and CEO of Venture Community Services

PHOTO/MATT WRIGHT

Mike Hyland, the president and CEO of Venture Community Services

Central Massachusetts went into the coronavirus pandemic with communities already facing deep-rooted challenges with poverty.

In Worcester, the household poverty rate in 2019 was 21%, according to the U.S. Census, more than double the state average. The rate was nearly as bad in Southbridge at 19%, and it exceeded 13% in Fitchburg and Leominster.

Add a pandemic that’s forced more than 800,000 Massachusetts residents to file for unemployment, and Central Massachusetts agencies whose missions are to fight food, housing, health and other challenges of poverty have been sent into overdrive.

“This is very much a poor person’s crisis,” said Jonathan Cohen, a program officer for the Greater Worcester Community Foundation, which has helped raise millions of dollars for dozens of community groups suffering during the pandemic.

The foundation moved fast, using its own discretionary funds to launch a special fund in mid-March, called Worcester Together, to help those it knew would need the most help: those without health insurance, healthcare workers, seniors and those with language barriers.

By May 4, the fund was approaching $6 million. GWCF partnered with the United Way of Central Massachusetts and the City of Worcester on the fund.

“We have been very amazed at the generosity of the community,” said Barbara Fields, the foundation’s president and CEO. “Extraordinary times have led to extraordinary responses.”

Making major sacrifices

Other Central Massachusetts agencies have responded, too. The effort has included those agencies’ own workers sacrificing their own health to take care of their clients, who themselves – whether older or developmentally disabled, for example – are often more medically vulnerable.

At Sturbridge-based Venture Community Services and Worcester-based Open Sky Community Services, employees have temporarily moved into residential group homes so they can continue providing care without potentially bringing the virus with them from home.

“It’s a forgotten workforce, and because it’s forgotten, they don’t have the economic wherewithal to stop working, even if they wanted to,” said Mike Hyland, Venture’s CEO.

Ken Bates, the Open Sky president and CEO, estimated 30 to 40 workers at Open Sky have elected to work in pairs living at group homes.

“It amazes me that they're doing it, and there are many more willing to do it,” Bates said. “It’s unbelievable to me that these folks continue to do that.”

Compounding the problem for human services agencies is the vulnerability of their own workforces. A typical nursing assistant makes $28,540 a year, and a personal care aide $26,440, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Our workforce is extremely vulnerable to this crisis,” said Jeffrey Kinney, the chief of staff at Worcester’s Ascentria Care Alliance. “We frequently saw when we have planning sessions internally that a lot of our employees are one step away from being our clients.”

A big community in need

Other service workers – those less likely to be able to work from home – are at greater risk, too.

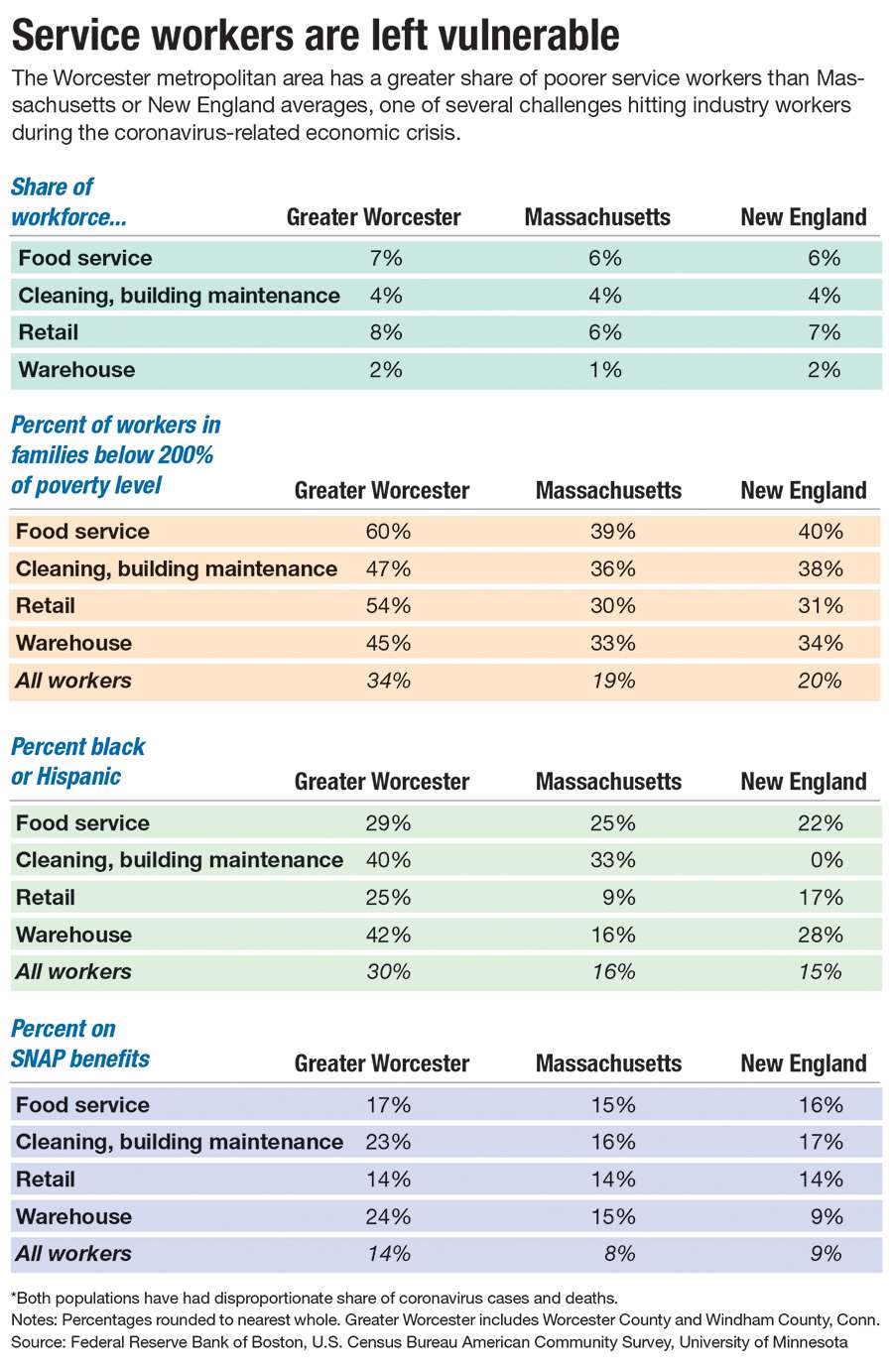

In food service, 60% of workers in the Worcester metropolitan area are in families making 200% or less of the poverty rate, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of Boston report in March. That compares to 39% among food service workers statewide and 34% for all workers in the Worcester area.

Among warehouse workers in Greater Worcester, 42% are black or Hispanic – two segments of the population hit disproportionately hard by coronavirus – and 40% of cleaning and building maintenance workers are in that category. That compares to 30% of the overall Worcester area workforce.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston warned the pandemic could exacerbate existing inequalities, including for the nearly 2 million service workers in food service, warehouse and similar work across New England. The federal CARES Act, which commits funds for small businesses and individuals, can help, but not enough to offset longer-standing problems, the Fed said.

Since the Great Recession, low-wage workers have seen no wage growth, and they’re now entering a sudden recession potentially far worse than the one ended more than a decade ago, the Fed’s report said.

In Worcester County, nearly 9% of the population and 12% of children are estimated to lack access to enough healthy food, according to the nonprofit Feeding America. That’s before many lost their jobs.

Some areas of Central Massachusetts have pockets of intense poverty.

One census tract along Chandler Street Worcester has a median household income of $23,036, one-third the Massachusetts median of $77,378. In Fitchburg, a downtown census tract has a median household income of $17,039, and half the neighborhood’s households live in poverty. The Irving Street corridor in Framingham has a median of $28,472.

“The pandemic is not creating the inequities but is deepening them,” Fields said.

An influx of support

GWCF diverts most of its funding to causes championed by donors. But it has some discretionary funds, and in mid-March, the foundation’s board voted quickly to set up a special fund for coronavirus-related needs.

A review process for grant applicants has been shortened to a 72-hour turnaround, as the foundation looks to get money into the hands of groups as quickly as it can. In less than two months, the fund has benefitted dozens of groups, including the Southeast Asian Coalition of Central Massachusetts to help immigrants and refugees, Rachel's Table to supply food pantries across Worcester County with milk, and the shelter Abby's House for additional staff and cleaning supplies.

The fund has given to health organizations to adopt telehealth technology, and for others to help with housing needs, food and access to health care and protective equipment.

The financial help is needed at a time when agencies are working hard to keep up with limited budgets and personnel.

Open Sky, another beneficiary, used funding from the foundation and elsewhere to hire 30 to 40 new staffers since the pandemic began. In February, the agency already had vacancies in 200 full-time positions it was looking to fill, Bates said.

“We’ve really focused a lot on homelessness and people on the edge, one rent check or paycheck away,” he said.

Venture Community Services is giving extra hourly pay to workers who volunteer to live in residential facilities to help limit their and clients’ exposure. State aid and Venture’s own cash reserves have helped, but the agency has still had to furlough roughly 140 workers, Hyland said – partly budgetary and partly because, with some staffers choosing to live in facilities, fewer workers are needed right now.

Ascentria, knowing it would have to reduce some workers’ hours and others would be facing heightened stress, started an employee fund for up to $500 in assistance.

“What our workers do is stressful in normal times,” Kinney said.

The Worcester Together fund is in the first of three envisioned phases. This first phase – already longer than Fields says she expected – is on emergency needs.

Later phases will be more strategically planned, with what are expected to be even greater needs. The emergency phase will be followed by a recovery and eventually a rebuilding and reimagining – hopeful terms for what is anticipated to be a brighter future.

Tim Garvin, the president and CEO of the United Way of Central Massachusetts, a partner with the Worcester Together fund, is among the optimistic.

“I don’t think I’ve ever been more excited and more scared at the same time,” he said.

Scared, Garvin said, because he hears about challenges of teachers trying to remotely work with students and sometimes having difficulty connecting, for example. He sees opportunities to make a difference.

“There has not been a day that’s gone by through all of this that friends haven’t reached out and said, ‘I’d love to help but with sheltering in place, what can I do?’ I tell them, whatever donations you give, anything will help,” Garvin said.

“We see this all the time,” he added. “When there’s a crisis, people step up, and they want to help.”

0 Comments