With new building codes on the horizon, battles will be fought in the name of progress, as developers and various interest groups are hesitant to make sweeping changes.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

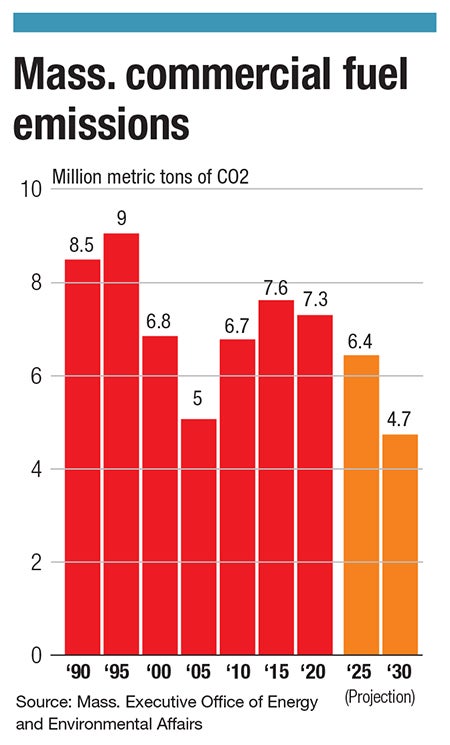

Massachusetts has more than 2 million buildings, and they are a major drag on the environment and the state government’s mission to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

Heating buildings with gas and oil makes up roughly 30% of statewide emissions, according to the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. This is a staggering number, as we need to keep our businesses, office buildings, warehouses, and homes from freezing during the winter. If there is to be a major change to help halt irreversible transformations of the climate, making buildings more energy efficient is a huge step in that direction.

At the same time, battles are fought in the name of progress, as developers and various interest groups are hesitant to make sweeping changes to make constructing the things their communities need more expensive and difficult to bring to fruition via constrictive rules.

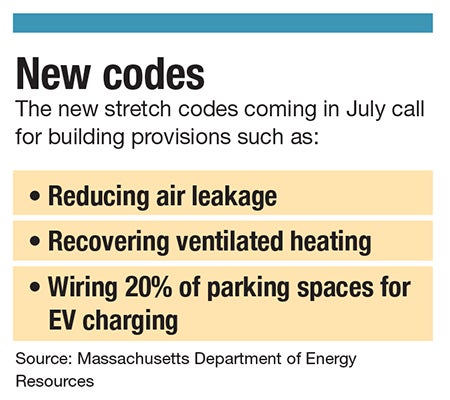

The first steps toward cleaner buildings started in 2008 when Mass. passed the Green Communities Act, which required the state government to update its building code every three years to ensure new buildings are designed while taking energy efficiency into account. On top of that, 290 Massachusetts communities wishing to receive funding as Green Communities are adopting a series of stretch codes, which tries to make construction more cost-effective and energy efficient than the base energy code. The latest updates were submitted on Sept. 22 and will go into effect in July.

This year’s updates to the stretch code include requiring multi-family development to wire 20% of parking spaces for EV charging; more stringent ventilation requirements through either heat or electricity recovery; and a more stringent Home Energy Rating Scores (HERS) index making it easier to build a home using electric heat.

“There is no way to reduce greenhouse emissions enough to reverse climate change unless we deal with buildings,” said Diane Jones, a member of Tipping Point 01545, a Shrewsbury organization seeking to eliminate fossil fuel hook-ups in new construction.

Not stifling development

On the other side, there’s businesses who see a bottom line and communities trying to create a business-friendly environment to bring jobs, homes, and residents to their community.

Community growth could be slowed by the additional costs coming with the new building codes, especially in regards to housing, which Central Massachusetts needs more of, said Roy Nascimento, president and CEO of the North Central Massachusetts Chamber of Commerce, which covers 27 communities, including Athol, Clinton, Devens, Fitchburg, Gardner, Lancaster, Leominster, Lunenburg, Orange, and Winchendon.

One of the issues for the chamber, Nascimento said, is the rules and provisions aren’t often clear. One developer was told to add more EV chargers to a parking lot, which would increase the cost of the project.

“Stretch codes are well-intentioned,” Nascimento said. “But [legislators] have to understand how they affect affordability before they’re adopted.”

Michael O’Brien, founder and principal of Galaxy Development LLC in Webster, which developed the retail center Trolley Yard in Worcester and Pleasant Valley Crossing in Sutton, is more blunt when asked about stretch codes.

“Big companies that can afford the extra cost seem to be fine with it,” O’Brien said in an email. “But that is not most projects and, like everything else these days, it seems to be hurting small businesses the most.”

But changes are happening whether small businesses and towns want them.

In August, then Gov. Charlie Baker signed the Act Driving Clean Energy and Offshore Wind, a comprehensive and expansive piece of legislation to end the sale of gasoline-powered cars in the state by 2035. Inside the bill were updates to the state’s building codes and an additional measure to allow 10 municipalities in the state to try out a pilot program banning fossil fuel heat in new buildings. The Town of Brookline has tried to ban fossil fuel twice since 2019, but both attempts were thwarted by then Attorney General Maura Healey, who is now governor, because the attempts violated state law. The new pilot program and stretch codes have given new life to the push to go electric.

Early adapters

Tipping Point 01545 is part of the Massachusetts Climate Action Network, a nonprofit fighting the climate crisis one town at a time, and, said Jones, wants to push her community to force developers to build all-electric buildings.

Jones has a different view than Nascimento and O’Brien, though, when it comes to costs and adopting new rules. She sees it as an opportunity for developers and contractors to learn about something new. If they do, they may out that the cost of building electric isn’t vastly different from putting in fossil-fuel burning systems. Early adapters have an opportunity to get ahead of the curve, because change is coming regardless.

“The tech has come really far,” Jones said. “Education is required, but the developer will reap economically.”

One company embracing the challenge to build electric is RODE Architects. The Boston firm has designed the planned nine-story building at the former site of Fairway Beef in Worcester’s Canal District to be 100% electric.

The only major difference between building an electric building and a fossil-fuel heated one is the size of the electric room, said Ruthie Kuhlman, an associate architect at RODE, because the units to heat and cool are often bigger than traditional furnaces and boilers. Otherwise, the system stays roughly the same inside. To meet compliance with the new codes, a certain amount of insulation is needed in the walls and around windows, which does limit some design ideas and features, but that’s not something Kuhlman is concerned with.

What everyone can agree on, though, is the rules around the new stretch codes need to be transparent.

“Most businesses want to play by the rules and do the right thing, but they need to understand the rules and they need more clarity,” Nascimento said. “The permitting process needs to be clear.”