One bill filed last year by Sen. Jason Lewis (D-Winchester), would require any public company headquartered in Mass. to have at least one female board member by the end of 2021.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

In 2003, Massachusetts became the first state to make same-sex marriage legal. It was the first to pass an equal pay law between genders in 2016, and the first to ban flavored tobacco last year.

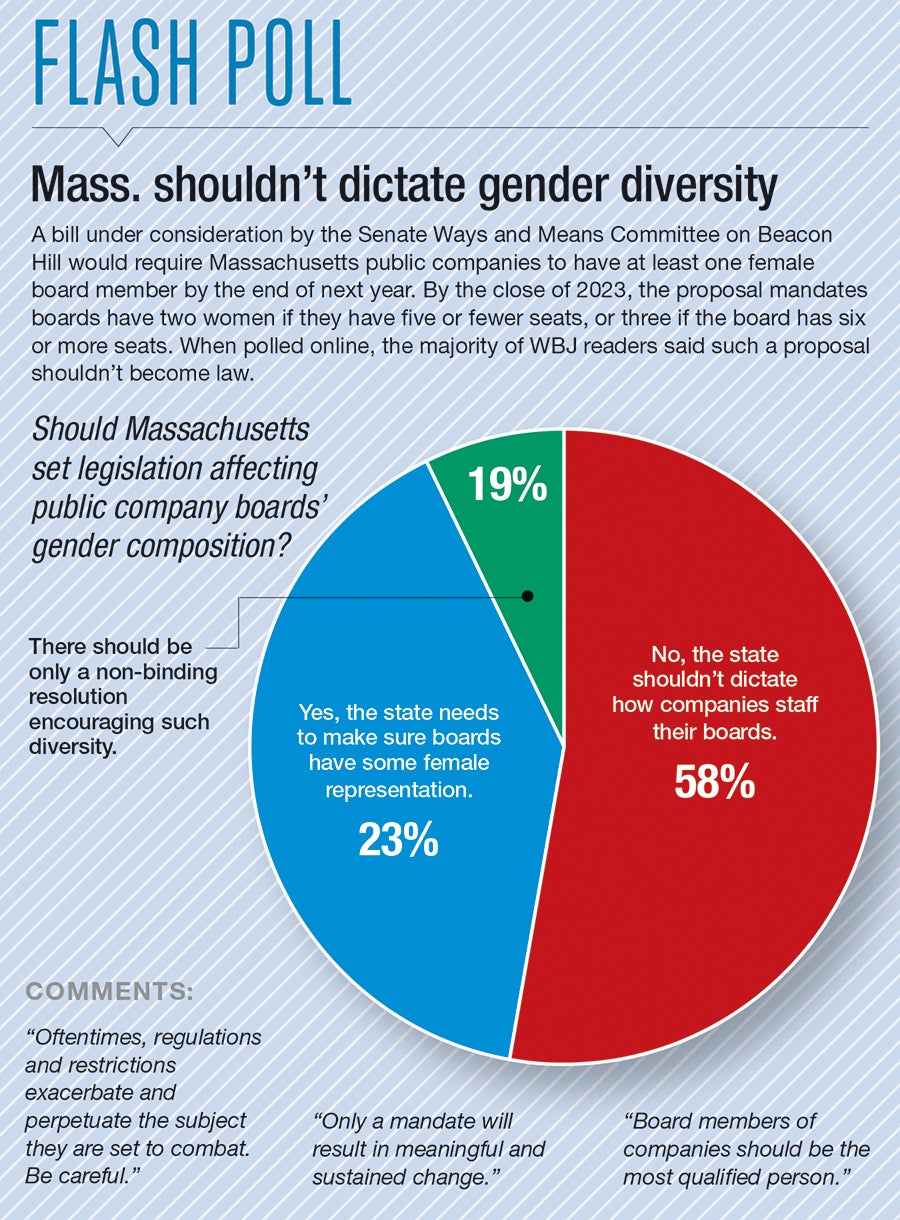

Massachusetts legislators are now looking for enough support for another progressive law: one to force public companies to add at least one woman to their boards of directors.

One bill filed last year by Sen. Jason Lewis (D-Winchester), would require any public company headquartered in Mass. to have at least one female board member by the end of 2021. Two years from then, boards would be required to have two women if they have five or fewer seats, or three if the board has six or more seats. Violations would reach as high as $100,000.

Other bills have attempted to chip away at the issue in similar ways.

One, filed by Rep. Patricia Haddad (D-Somerset), would require appointed state boards and commissions to have both gender and racial and ethnic diversity among their members. One gender couldn’t have more than twice the number of members as the other.

Another, filed by Rep. Liz Malia (D-Boston), would require any company with 100 or more employees to file a report each year detailing race and gender ratios of those in senior ranks.

In its annual The Boardroom Gap investigation into gender diversity among the leadership at 75 prominent Central Massachusetts business organizations, WBJ found female representation was lacking, as women fill 34% of executive ranks and board of director positions.

At the 16 Central Massachusetts public companies, women comprised 24% of board members.

Pushing the issue forward

Lewis filed the public company bill because he said companies haven’t made nearly enough progress on their own in broadening their leadership.

“I wish it wasn’t necessary to legislate greater diversity in positions of leadership in Massachusetts,” Lewis said. “Overall, we’re nowhere near where we need to be.”

Massachusetts has already taken small steps on the issue.

State Sen. Karen Spilka (D-Ashland), now the Senate president, filed a non-binding resolution in 2015 urging firms to have at least two female board members and report progress annually.

More tangibly, in 2018, Massachusetts became the first state to prohibit employers from requesting salary histories from potential hirees, a law aimed at curbing the gender pay gap. This Equal Pay Law bars employers from asking job candidates about their pay history, in an attempt to cut down the pay gap.

So far, the bills on public companies and public boards have advanced out of the State Administration and Regulatory Oversight committee but haven’t yet advanced to a full vote.

Lewis is encouraged they’ve made it out of committee, when a bill can easily get lost in the shuffle or face resistance from enough members to stall it.

“Just the fact that it’s being discussed is helping to push this issue forward on the agenda for many companies,” he said.

A template to follow

One state has already beaten Massachusetts to the punch: California, a state whose legislative actions have been known to have outsized influence on the rest of the country.

In California, a first-in-the-nation law requiring public companies to have at least one female board member by the end of 2019 has been met with almost total compliance.

California Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson, a Democrat originally from Newton, first filed a resolution in 2013 urging companies to add more women to their boards. She provided companies with studies showing those with higher rates of female participation tended to have better performance.

“We got nowhere,” Jackson said. “Clearly, adding women is a benefit, and yet we couldn’t get them to comply voluntarily.”

The financial services firm Credit Suisse found in 2019 public companies worldwide with more diverse management teams had a 4% better financial performance than those below the diversity average. A 2017 study by the recruiting firm Korn Ferry found both men and women to be more engaged when a board had a female member.

Jackson went a step further, filing a bill that became law in 2018 mandating for the first time all public companies headquartered in California have at least one female board member.

Of 650 public companies, only 16 didn’t comply, and they were mostly very small or in danger of being delisted as public firms, according to a study by Clemson University professors Daniel Greene and Vincent Intintoli, and University of Arizona professor Kathleen Kahle. Companies were most likely to add a member in December, indicating difficulty or reluctance complying.

Most companies – about three out of five – chose to add to their board to accommodate a new member, instead of replacing a male member with a female. Companies will need to add more than 1,000 female directors by 2021, when companies must have two or three female members, depending on the size of their board, the researchers estimate.

They see that need as more onerous than adding a single member, estimating a stock market cost of around 1.2%.

“It works out to be a pretty big economic number,” Greene said.

The law was not without resistance.

The bill was opposed by the California Chamber of Commerce and 19 other chambers and employer groups, who argued the bill wrongly considered only one element of diversity, and violated state and federal constitution because an existing or potential board member could be excluded on the basis of gender.

Challenges have been filed against the law in court.

One claims the law violates equal protection under the U.S. Constitution, and another says it would violate the California Constitution by using taxpayer funds, according to the Associated Press.

Laws have shown results

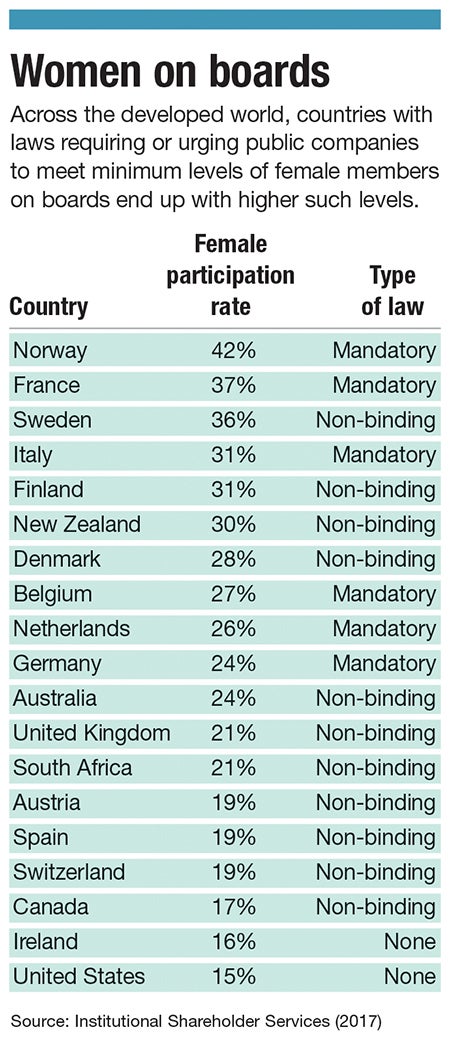

Where legislation has forced the issue, the results have been clear.

In Norway, a law requires as many as four members of each sex on a nine-member public company board, and the result has been the world’s highest rate of female inclusion on corporate boards. Norway women held 42% of board seats in 2016, according to a study by Maryland advisory group International Shareholder Services. The country requires at least two members of each sex on a four- or five-member board, three of each on a six- to eight-member board, and four of each on a nine-member board.

Other countries in Scandinavia and Western Europe have followed closely behind.

France, which has a strict law, and Sweden, whose legislation is less forceful, each boast rates of 36% or more for female board participation. Finland and Italy exceed 30%, and Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark are among those with rates more than 20%.

The United States, by contrast, is at 15%, according to a 2017 study of 3,000 companies by International Shareholder Services, Inc.

Norway – a wealthy country known for its progressive attitudes – wasn’t always open to the idea of quotas, according to a study last year by three Norweigan researchers. The prospect of requiring women on boards first surfaced there in the late 1990s, and the law was enacted in 2003. It went into full effect in 2008.

The legislation didn’t attract broad attention among Norwegians, and eventually the business community was split between opponents not wanting to be forced into decisions and those who saw no other option to spur change, said Mari Teigen, a researcher at the Institute for Social Research in Norway, and one of the study’s authors.

In time, the study found, support grew, particularly among male business leaders.

“Today the opposition has more or less vanished,” Teigen said.

That’s not to say change would have taken place without the law.

Public companies subject to the law had women in 6% of board seats in 2002, the year before the law was approved, according to Statistics Norway, the country’s official data agency. By 2017, it was 42%.

Limited liability companies, on the other hand, weren’t required to change their board compositions. In their case, female participation rose from 15% to 18% over those 14 years.