In theory, increasing the supply of market-rate housing to meet a growing demand eventually gets more residents housed and drives down the median rent.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Central Massachusetts saw an 8% population growth over the last decade, signifying the need for more housing. In response, many communities are constructing new housing developments, but the impact of those projects may actually be leaving significant portions of the population unhoused.

“The rate of new construction and adaptive reuse [into] market-rate housing is something we just haven’t seen before,” said Andrew Howarth, director of development at Worcester Community Housing Resources, a nonprofit which aims to provide affordable housing for Worcester County. “It's a trend that demands a high market rent because construction costs are expensive, and especially expensive nowadays.”

In theory, increasing the supply of market-rate housing to meet a growing demand eventually gets more residents housed and drives down the median rent.

Like everything else, however, the coronavirus pandemic has turned that notion on its head.

“All of the academic metrics aren’t working,” said Howarth.

The city of Worcester has a rental vacancy rate of 3.4%, according to a May report from the Worcester Regional Research Bureau, which is about 1 percentage point lower than the state average. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development reported the rate of homelessness in Massachusetts has grown 11% over the last decade.

As Boston development becomes unaffordable, many Boston-area investors are looking toward Central Massachusetts where the cost of real estate is lower, but revenue returns are still high.

“We have a surplus of investment cash, a tight tight vacancy rate, and relatively low acquisition costs compared to the Boston market,” said Howarth. “Add in doubling construction costs and a pandemic, and that's the perfect storm.”

A changing market

The greatest hole in the housing market is the lack of what Jennifer Schanck-Bolwell calls deeply affordable units. Schanck-Bolwell, WCHR’s executive director, said even units designated as affordable are often inaccessible to those making below 50% of the median wage.

Central Massachusetts’ low vacancy rates exemplify a need for more housing developments, but incentivizing developers to include affordable units can be a substantial challenge.

Municipalities usually try to collaborate with developers by asking them to give something back to the community, such as improving a street, adding some trees, or including a few units of affordable housing, in return for approving a large, high-revenue project.

This collaboration can become a delicate balance of not discouraging a developer from creating housing, as adding more than a couple units of affordable housing eats into a developer’s rental revenue.

“Generally, in a development, they may have deeply affordable ones, but it might be one or two units out of 50 units. So does it help? Of course, every unit put online helps. Does it make a dent? Maybe not as much,” Schanck-Bolwell said.

As wealthier investors become interested in the region, and inflation rises with a particularly stark impact on construction, developers are looking for even higher revenue returns to offset the cost of building, said Dan Botwinik, who is the founder of Boston real estate company Cougar Capital Management, Inc. and has projects in Leominster and Shrewsbury.

“At a certain point, if the rents aren't high enough, the developer doesn't think that the effort and the risk [are] worth the reward,” said Botwinik. “Instead of trying to build a project, if somebody wanted to get a return on their capital, they could go buy an existing building … The incentive might not be there to get the housing created – or any housing created.”

Botwinik said other ways make it easier for investors to build, like limiting parking requirements for projects near public transportation to cut construction costs so developers will be more open to affordable units.

Besides developers, it’s mainly up to nonprofits to get deeply affordable housing built, but the region’s hot real estate market is making that an even greater challenge.

Howarth said he receives roughly two calls a week from developers asking if WHCR is willing to sell any of its properties. Acquiring new sites on which to construct affordable housing is getting harder.

“We’re increasingly dependent on institutional sellers or government sellers or on receiverships to afford sites for affordable housing,” he said.

Banks, once anxious to get rid of code-violating buildings and hand them over to nonprofits at a deflated price, are now holding onto these properties because of their rising value. Instead, banks will often pay the residents to leave so the building is unoccupied and thus not subject to code inspections, said Howarth.

Finding a healthy balance

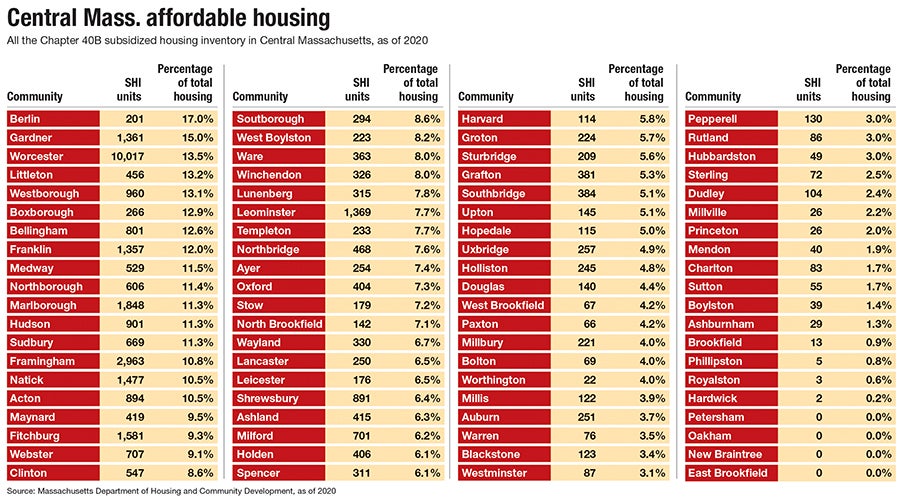

Not every Central Massachusetts community is starving for affordable housing. With 1,360 units of affordable housing, 15% of the housing in Gardner is affordable, one of the highest percentages in the state.

Still, Gardner’s high numbers don’t offer any easy solutions; the community is still struggling to find the right balance in its housing market.

The city’s director of community development and planning, Trevor Beauregard, said state incentives for building affordable housing, like low income housing tax credits, are some of the only ways to attract investors to build housing in Gardner.

“We’d like to see a lot more market-rate because obviously that attracts more professionals with disposable income, which we want to see in the community in our downtown,” Beauregard said.

The average rent in Gardner is $950, according to the housing listing website Zumper, significantly lower than Worcester’s $1,350. The low rents make it infeasible to develop in Gardner without bringing in free equity through grants and tax credits, Beauregard said.

“To create a healthy economy, you have to have a healthy mix, right? You can’t just have one type of housing, you need to have all types of housing,” he said.