If there is an industry that stands to dramatically contribute to climate change mitigation, it’s building design, and Central Massachusetts architects say they’re poised for the challenge.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

If there is an industry that stands to dramatically contribute to climate change mitigation, it’s building design, and Central Massachusetts architects say they’re poised for the challenge.

Clay Benjamin Smook, owner of SMOOK Architecture and Urban Design in Westborough, said in general, steep limitations aren’t a bad thing when designing a commercial or residential building. “It’s better, the more constraints you have, it really pushes you,” Smook said.

Smook, like most of his comrades in architecture, didn’t get into the business to save the planet when he started in the late 1980s, but he’s unfazed at the idea that buildings, more than ever, must be designed to meet stricter energy codes and built to withstand a growing threat of natural disasters ushered in by a changing climate.

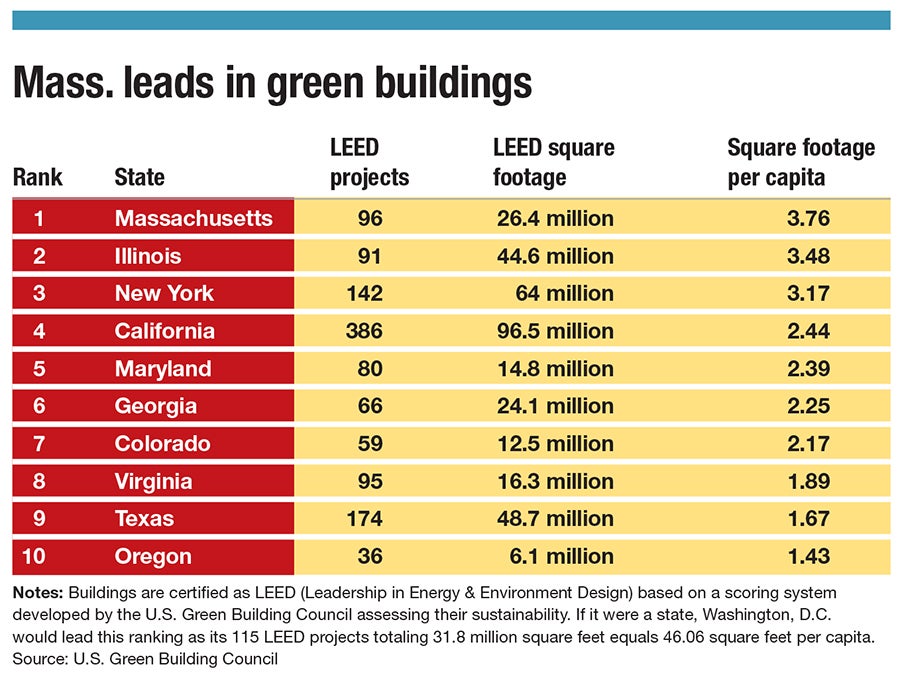

Massachusetts, like California on the West Coast, has always been on the forefront of sustainable building, and programs such as the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification program, a global gold standard for green buildings, are nothing new. Smook said there’s a cost benefit to building for energy efficiency, and sustainability is important to public perception of a company.

But the stakes are rising. International building and energy codes, released every three years, are preparing for the possibility of flooding in coastal cities, stronger earthquakes, and hurricane winds. In The Seaport District in Boston, that means floodgate designs on new buildings, and anywhere within a mile of the coast is facing down more stringent wind and earthquake codes.

“It’s slow to happen, but it’s happening,” Smook said.

Taking the lead

Rather than simply adapting to codes, the architecture industry appears to be taking the lead on sustainable design for a changing climate. In June 2022, The American Institute of Architects (AIA) announced the Framework for Design Excellence, largely in recognition of what it called the climate emergency. The principles of the framework, AIA said, foster net-zero carbon emissions buildings that are healthy for people and the environment, and resilient.

There’s a huge opportunity for the industry to curb climate change. Buildings are responsible for 40% of global carbon emissions generated by building operations, building materials, and construction itself, according to New Mexico-based nonprofit researcher Architecture 2030.

The goal of the organization is to eliminate all carbon emissions from the built environment in order to help meet the lofty goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement: to hold global temperatures to no higher than 1.5 degrees Celsius over pre-industrial levels to avert environmental catastrophe.

Training the next generation

In the world of academia, much of the conversation has settled on de-carbonization of buildings, said Shichao Liu, assistant professor of civil, environmental and architectural engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. WPI is teaching aspiring architects and engineers the skills to build for climate change, and with a passion for art and design, they are driven by the charge.

“They can build something to change the world,” Liu said.

Decarbonization of buildings, Liu said, involves using materials not producing much carbon during production – such as reclaimed materials and natural materials that don’t need to be manufactured – and looking at the emissions involved in harvesting and transporting those materials to a building site.

The other important focus is resiliency. With climate change, a major emphasis is placed on designing for heatwaves and related blackouts, flooding, and wildfires, Liu said. Passive building design, which includes natural heating and cooling methods for energy efficiency, complements proactive measures, such as use of flame retardant materials in a city building and backup power systems for cooling during blackouts.

“When engineering meets art, there are a lot of interesting ideas,” Liu said.

With Massachusetts being a leader in sustainable buildings, local architects have already logged years worth of projects with elements of green design, and momentum keeps gaining. Smook, of the Westborough firm, said it’s exciting to always be on the edge of new building techniques. Smook had a 4,200-square-foot office building in downtown Westborough go through a lengthy public approval process. That kind of vetting requires people to check their egos at the door, he said, but it was well worth it.

Built in sections, the Westborough building is superinsulated and includes solar panels generating power back into the grid. The building features a pre-cast foundation craned into place during the winter, which speeded up construction. Smook said it’s the first of its kind he’s aware of in the area, and it’s one of the first new buildings in Westborough’s downtown district.

“It’s storytelling. It can be so powerful,” Smook said, of the building process.

Constructing the future

If the design industry is trailblazing for carbon neutral building construction, local cities and towns are shaping the pathway forward for energy efficiency. Many have moved to adopt a high-efficiency building energy code, known as a stretch code, created by the state to meet the goal of becoming a net-zero emissions state by 2050.

Kevin Provencher, Worcester office director at Norwell-based Habeeb & Associates Architects, said the City of Worcester has expressed interest in adopting the latest energy stretch code on an accelerated timeline – by next summer. While such measures may drive up the cost to build, Provencher, who specializes in LEED projects and sustainable design, believes the market will adapt quickly. Energy-efficient systems, such as geothermal and solar systems, are a part of nearly every commercial building project in the region.

“Any kind of renewable energy resource is going to become very important,” Provencher said.

The nature of sustainable building design is that it’s always changing, said Steven Burke, director of sustainability at Consigli Construction. The Milford construction management firm generates 60% of its revenue from sustainable projects and is on the cutting edge of sourcing low-emissions materials.

Burke said he expects an upcoming Consigli project will be the first of its kind in the region to use a concrete mix that replaces cement with ground glass, greatly reducing the carbon footprint. Looking ahead, Burke said industry will take a hard look at the supply chain and how equitable labor practices.

“The question is always, ‘How do we do the next thing and continue to do it better?’” he said.