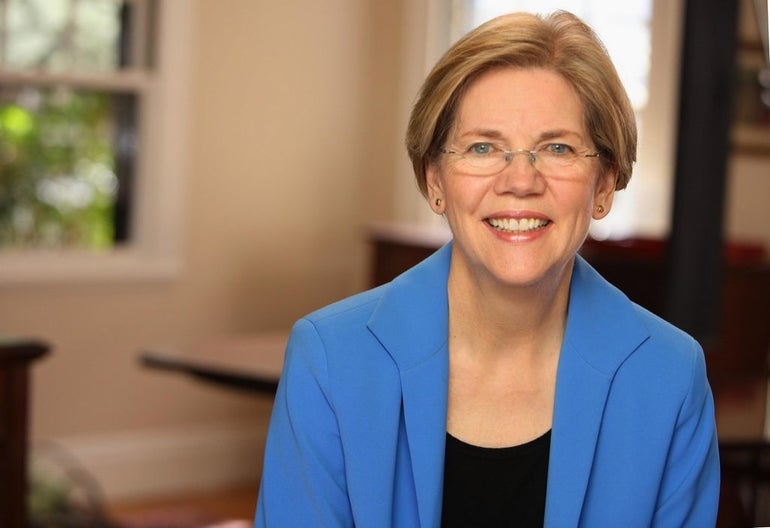

After weeks of sounding the alarm about the downsides of interest rate hikes, U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren thinks the more modest approach the Federal Reserve took with its latest increase is still pushing the envelope too far, too fast.

The Federal Reserve on Wednesday bumped up its benchmark interest rate by half a percentage point, pushing the target range for the federal funds rate to between 4.25 percent and 4.5 percent.

That hike was smaller than previous increases approved this year, an indication that rampant inflation may be slowing, but it builds on a long stretch of the Fed attempting to deflate demand in a way that continues to rankle the senior senator from Massachusetts.

“Rate hikes imposed by the Fed have been extreme,” Warren said in an interview with the News Service. “They’re high and they’re fast, and they come at a time when the cause of high prices is linked to events like supply chain kinks and corporate price-gouging that are not within the control of the Fed or affected by higher interest rates.”

The Democrat, who also detailed her focus on climate priorities in the next session, said she believes the Fed is wielding interest rate hikes as the “only response” to inflation that has pressured American families for months, an approach she called dangerous.

Federal Reserve officials signaled they expect to continue pursuing additional increases to the interest rate target range over the next year as they try to wrangle rising consumer costs, and they also expect joblessness will increase as a byproduct.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said this week that the median unemployment rate projection for Fed officials is now 4.6 percent at the end of 2023, which would represent an increase over the 3.7 percent nationwide unemployment rate in November.

Earlier this year, Powell warned that Americans should brace themselves for “some pain” as a result of efforts to slow inflation, and on Wednesday he argued that the tradeoff is worthwhile.

“The largest amount of pain, the worst pain would come from a failure to raise rates high enough and from us allowing inflation to become entrenched in the economy so that the ultimate cost of getting it out of the economy would be very high in terms of employment, meaning very high unemployment for extended periods of time, the kind of thing that had to happen when inflation really got out of control and the Fed didn’t respond aggressively enough or soon enough in a prior episode, you know, 50 years ago,” Powell said Wednesday, according to an official transcript. “So that’s really the worst pain would be if we failed to act.”

“There will be some softening in labor market conditions. And I wish there were a

completely painless way to restore price stability. There isn’t,” he added. “And this is the best we can do. I do — I do think, though, that — and markets are pretty confident, it seems to me, that we will get inflation under control. And I believe we will. We’re certainly highly committed to do that.”

Referencing Powell’s past comments about “pain,” Warren said, “It means people will lose their jobs, people will get laid off from business cutbacks.”

“The Fed has a dual mandate: inflation and jobs,” she said. “I’m pressing him to say more about what it means if he keeps raising interest rates and pushes this country into a recession that costs millions of people their jobs. I’m waving the warning flag here.”

Warren and several of her colleagues, including Congressman Stephen Lynch, wrote to Powell on Oct. 31 voicing concern that an overaggressive approach toward interest rates could unnecessarily put hundreds of thousands of Americans out of work.

They asked for specific Fed estimates on how many job losses would accompany projected increases in the unemployment rate, how those effects would break down among different demographic groups, and whether the Fed has seen evidence that “its monetary policy actions have embedded expectations of recession among market participants and consumers.”

Lawmakers requested answers by Nov. 14, and more than a month later, Warren said she still has not received a reply.

A Federal Reserve spokesperson said the agency received the letter from lawmakers and plans to respond.

Another priority on Warren’s mind heading into a new session in Washington, D.C. is building on climate policy momentum Democrats secured during President Joe Biden’s first two years in office.

Clean energy, climate change resilience and emissions reduction featured as areas of focus in the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure law, the Inflation Reduction Act, and a chips manufacturing and science spending bill.

Warren, who touted her work to craft a 15 percent corporate minimum tax as a key step in development of the Inflation Reduction Act, said that bill in particular is a “powerfully important package” but cautioned it does not go far enough.

“It’s a big basket of carrots. There are no sticks in it,” Warren said. “The only way that we could get a climate deal that every Democrat would sign off on was by putting incentives in to make changes on climate.”

She urged lawmakers to turn their attention to that second, more forceful option for reforms and consider “restrictions” she believes will be necessary to ensure transition to a cleaner, more reliable power grid and curb greenhouse gas emissions.

That will prove enormously difficult: when Congress approved the legislation that Warren views as containing “no sticks,” Democrats controlled both branches and the White House. Next term, they’ll maintain Senate control and the presidency but shift to the minority in the House as Republicans — who opposed the Inflation Reduction Act — take the majority.

“It’s going to be even tougher with half of Congress in the control of Republicans and particularly with new members on the House side who have made clear that they’re coming to Washington for one purpose only: to get Donald Trump reelected,” Warren said. “That means they’re not here for the nitty-gritty work of climate policy and tax fairness.”

Warren added that she is optimistic on another climate front: scientific innovation, which she believes will play a key role in long-term climate policy.

The so-called CHIPS and Science Act nearly doubles funding for the National Science Foundation to $81 billion over the next five years.

“That takes us not just past the divided government of the next two years, but takes us well on into the future,” she said. “That work will proceed regardless of the kind of chaos Republicans want to cause in the House.”