Six years after cannabis legalization, the fledgling industry remains unequal. But two new bills aim to make good on that promise of bringing equity.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

The legalization of adult-use cannabis in Massachusetts in 2016 signaled a new era in the state’s attitudes towards the crop. Once villainized during the War on Drugs, its legalization opened the doors for a plethora of new legal dispensaries, along with a new stream of cash for municipalities willing to benefit from this new method of income.

Baked into the ballot initiative and later the 2017 law setting up the regulation for the industry was the need of righting historical wrongs brought on by the drug’s former criminalization. Many remained incarcerated for selling a drug that was now legal. Many poor communities, and communities of color, had been particularly targeted in the name of the War on Drugs. If cannabis was going to be legal in the state, then the industry need to be designed in a way to make sure those harmed by its illegality would benefit.

Now, six years after cannabis legalization in Massachusetts, it’s clear the fledgling industry remains unequal. The industry remains overwhelmingly white and male: According to data from the Massachusetts regulatory body Cannabis Control Commission, 79% of marijuana establishments are owned by white men, compared to 10% owned by people of color. In terms of gender, 92% are owned by men and 8% are owned by women.

But two new bills, introduced by the Massachusetts Senate and House of Representatives, aim to make good on that promise of bringing equity to the cannabis industry. Both bills have resoundingly passed in their respective chambers, and they now await a legislative committee to consolidate both bills into one, which will then need to be voted on again by the House and Senate before the end of July. Once passed, it needs the governor's signature to go into law.

“This is the first really consolidated omnibus bill that has happened since the legalization of adult-use cannabis in Massachusetts,” said Jen Flanagan, the director for regulatory policy at the Boston office of Vicente Sederberg LLP, a law firm specializing in cannabis law and helping draft legislation for cannabis bills in multiple states. “It’s a really big deal.”

Funding social equity & limiting HCAs

Flanagan, who previously served on the CCC, as well as in the state Senate and House, said the bills, which passed in the House on May 18 and the Senate in April, puts a mechanism in place to create a trust fund to support the the commission’s social equity program, which supplies training and technical assistance to aspiring cannabis entrepreneurs in areas which have been disproportionately impacted by the War on Drugs.

The CCC lists 29 towns and cities as areas of disproportionate impact. It includes four of the five largest cities in the state (Boston, Worcester, Springfield, and Lowell) but only counts certain census tracts within those cities.

The bills’ second key provision is greater transparency for the host community agreements that marijuana businesses must obtain from the city or town governments where they operate. The 2017 law passed by the Massachusetts legislature capped the fees and taxes host communities could collect at 3%, but the CCC declined to enforce that provision in the agreements, saying it didn’t believe it had the authority.

That led to HCAs becoming a pay-to-play system, said Adam Fine, a managing partner at Vicente Sederberg.

“There was at least a perception that the more well-funded operators would just kind of offer more,” Fine said. “The cap was supposed to be at 3% of gross sales, but people were actually giving more than that, in offering charitable donations and offering to pay for sidewalks and police detail and all these other things.”

The lack of oversight meant some municipalities charged more than the cap, effectively extorting marijuana establishments. The most egregious case of this occurred in the Fall River, where former mayor Jasiel Correia was sentenced to six years in prison for fraud and corruption after being convicted of extorting cannabis businesses.

The new consolidated bill will look to ensure the 3% cap, as well as require municipalities to disclose where money received through an HCA will be spent, said Fine.

“It gets rid of any of the ambiguity in the language,” he said. “It’s absolutely clear that 3% is the max, and importantly, you’re going to have to document the actual cost.”

Central Mass: the cannabis capital

The first major reform of cannabis legalization in the state is of particular importance to Central Massachusetts, which data shows is the center of the cannabis industry in the state. According to the CCC, 220 marijuana establishments are based in Worcester County, more than the next two counties, Middlesex and Plymouth, combined; and the CCC is based in Worcester’s Union Station.

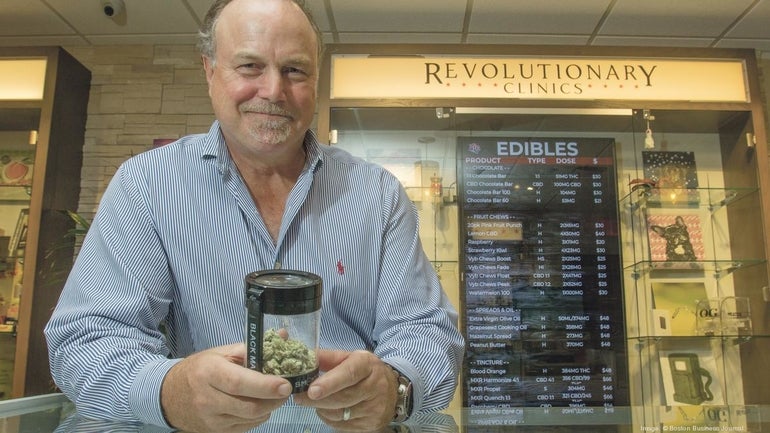

Keith Cooper, who runs the grow facility and dispensary chain Revolutionary Clinics, said he was supportive of the new policies the bills plan to introduce. Revolutionary Clinics operates several medicinal dispensaries across the state, but its grow facility is based in Fitchburg, one of the 29 towns designated by the CCC as an area of disproportionate impact.

“One of the biggest stumbling blocks that everyone has is capital to get business,” said Cooper, who earned an MBA from Harvard Business School in Boston and has founded startups in several other industries before entering the world of cannabis. “There’s your regulatory fees. There’s leasing and rental fees, and all of those things are very expensive. Creating this trust fund for those entrepreneurs is a wonderful advancement in the industry.”

Cooper said the bill would help fix the historical injustices the War on Drugs brought to communities across the state.

“We had advocated for a long time to put some kind of fund in place,” he said, “which is effectively what they’re doing here, and getting [the funds] into the hands of people that need it so they can get a seat at the table. Because part of the goal of the industry is to even things out a bit.”