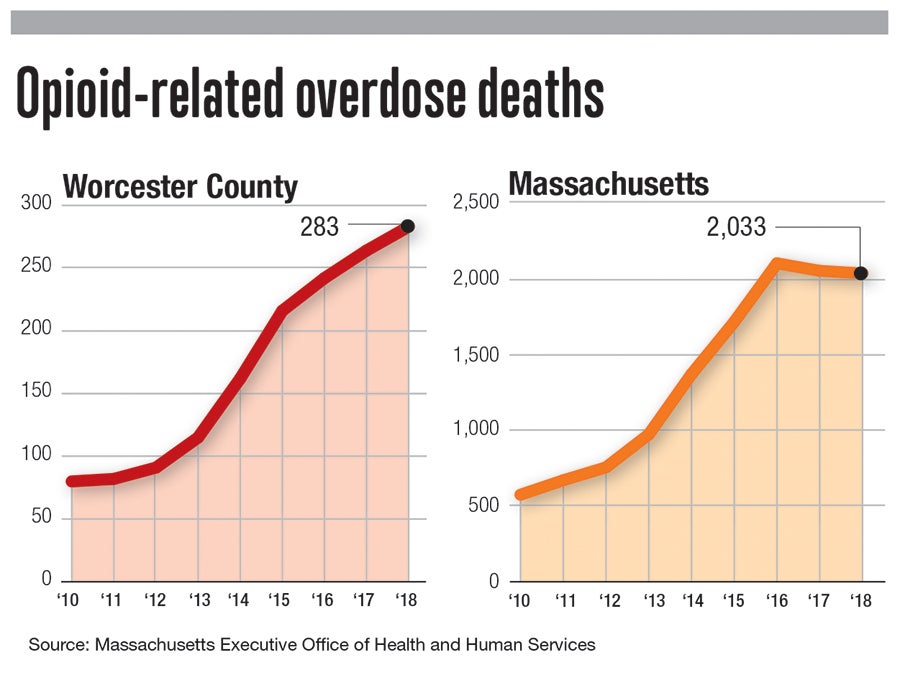

A report in May brought troubling news for Worcester: In 2018, 97 city residents died from opioid overdoses, the highest number ever recorded, up from a previous high of 82 in 2015. Worcester County also hit a new high of 283 deaths from overdoses of the drugs.

In contrast, the report – produced by the Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services – found the statewide numbers declined slightly for the second year in a row, from a high of 2,100 in 2016 to 2,033.

In a city of close to 200,000 people, an additional 15 deaths could be chalked up to a couple of unusually strong batches of drugs hitting the area, or just random chance. But to Dr. Matilde Castiel, the city’s commissioner of Health and Human Services, the numbers suggest improvements in local institutions’ approach to the problem haven’t yet accomplished enough.

“We overall have done some impressive things over the past number of years, but it takes some time to change,” Castiel said.

Initial efforts

When the city hired Castiel, a doctor with a background addressing substance use disorders, in 2015, it was part of a broader effort to focus resources on the opioid problem.

Already, she said, the city had a task force working with homeless people in encampments, many of whom deal with addiction.

UMass Memorial’s Community HealthLink now offers 24-hour urgent care support for people with drug use problems. New recovery homes are opening up in Worcester. And the city in May rolled out the new app Stigma Free Worcester, created in partnership with Worcester Polytechnic Institute, to help residents find resources like housing, clothing, mental health support and addiction treatment.

Dr. Pamela Tsinteris, director of Office-Based Addiction Treatment and the Chronic Pain Program at Family Health Center of Worcester, said she’s seen a big improvement in recent years in medical providers’ attitudes toward substance use treatment.

“A few years ago, just a few people were willing to treat addiction,” she said. “We’ve really had an increase in the number of people providing this care.”

Tsinteris said, in the past, practitioners’ only experience with addiction was encounters with people who tried to hide their drug problems in order to seek opioid pain prescriptions.

Those encounters are often confrontational and uncomfortable, Tsinteris said, but when practitioners demonstrate they see addiction as a disease rather than a moral failing, they often find people in recovery are eager to work with them.

Fighting addiction with drugs

In both community settings like Family Health Center and larger institutions like the UMass Memorial Health Care system, increasing numbers of doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician’s assistants are getting trained and receiving federal waivers allowing them to prescribe buprenorphine. The drug, often combined with another medication called naloxone and sold under the brand name Suboxone, helps people avoid withdrawal symptoms and physical cravings when they stop using drugs like heroin or fentanyl.

“It’s kind of a miraculous drug in some ways,” said Dr. Christopher Kennedy, chief of psychiatry at UMass HealthAlliance Hospital in Leominster. “It can allow people to think about getting a job, taking care of their family, as opposed to getting their next fix.”

HealthAlliance has formed partnerships in the surrounding communities. Like health institutions and campaigns in Worcester, the partnerships are helping make the overdose reversal drug naloxone, or Narcan, widely available. HealthAlliance is working with recovery coaches, people who have been through addiction themselves and can help others like them.

Helping people in recovery succeed

One longstanding institution demonstrating how people in recovery can help each other is Café Reyes, a restaurant and catering company on Shrewsbury Street that Castiel helped create before going to work for the city. The café employs men who have gone through treatment at the Hector Reyes House, which serves Latino men in recovery.

“A lot of them have been incarcerated, and for a lot of them they have not had jobs,” said Dr. Aaron Mendel, who is the executive director of the organization, as well as a UMass physician and Castiel’s husband.

Mendel said the business allows the men to learn both specific jobs skills and soft skills like workplace communication. It presents a positive public face of recovery.

“When you walk in, you don’t know who in the restaurant serving you or sitting in the restaurant is in recovery,” he said. “Just because they have a substance abuse issue doesn’t mean they’re any less charming or less capable.”

Beyond helping people succeed in recovery, Castiel said local officials and health providers are working to address the social issues creating fertile ground for substance abuse. That means things like helping people leaving jail or prison to get jobs and housing, and supporting public school students who have experienced trauma and high levels of stress.

But those efforts won’t have immediate results in stopping overdoses. Meanwhile, healthcare officials are seeing a continuing rise in the prevalence of the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl. Castiel said dealers are now mixing the substance not just into other opioids like heroin but in drugs like cocaine and marijuana too.

To really get a grip on the overdose problem, Castiel said, it’s crucial for providers to become allies to people with addiction. She said only 20% of people with substance-use disorders seek help. Others are often worried about being punished as criminals for their drug use or stigmatized by healthcare systems.

“For a long time, people with addiction and mental health problems have been marginalized,” Castiel said. “You can go into places and be treated horribly, and people will not go back.”

Tsinteris said medical approaches are gradually shifting, becoming less judgmental and more focused on maintaining provider-patient relationships and helping drug users to keep themselves as safe as possible.

“It’s helped simplify things, helped people be honest,” she said. “They don’t have to lie and hide it if they relapse.”