In February, Gov. Maura Healey declared Massachusetts is facing a mental health crisis.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

In February, Gov. Maura Healey declared Massachusetts is facing a mental health crisis.

For those in the industry, this isn’t news. One in five people live with a mental health condition, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, and Central Massachusetts is struggling to keep up with the demands this places on care systems.

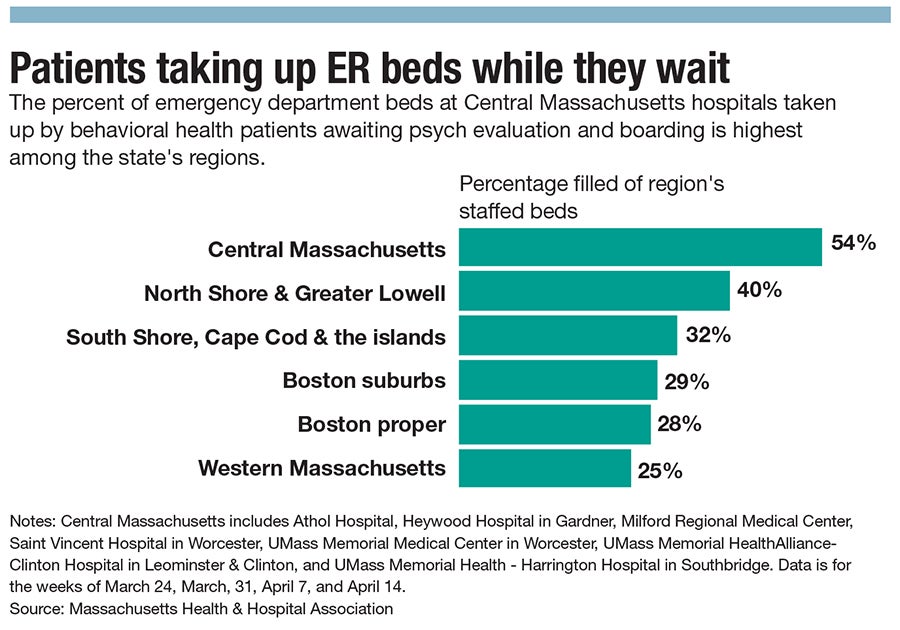

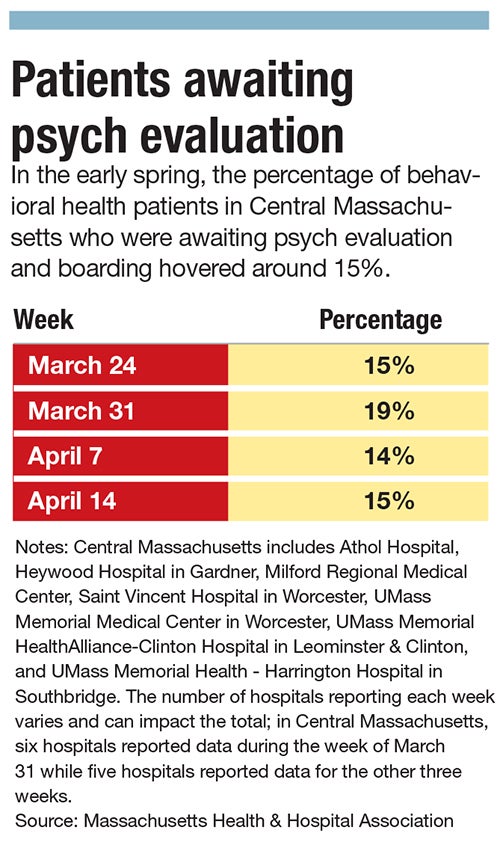

Between March 24 and April 20, Central Massachusetts saw its behavioral health patients awaiting evaluation and boarding take up as much as 54% of its emergency department bed capacity, the highest rate of any other Massachusetts region by at least 14 percentage points, according to the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association.

“We all should be concerned about the state of the mental healthcare system in Central Mass.,” said Ken Bates, president and CEO of Worcester human services nonprofit Open Sky Community Services.

Collaborating on equitable programming, exchanging resources, and sharing institutional knowledge are all ways Central Massachusetts nonprofit leaders see the region navigating challenging times. Though not a solution to the systemic shortage of reserves, they believe the region still has power to drive meaningful change.

“One of the best things we can do is collaborate, because there's more than enough work to go around,” said Kathleen Jordan, president and CEO of Worcester nonprofit Seven Hills Foundation.

Regional pain points

For Jordan, the most significant challenge within the region’s healthcare system is the workforce shortage.

Nearly one-third of the 32 most in-demand occupations in Central Massachusetts requiring an industry recognized credential are in healthcare and human services, according to the Massachusetts Department of Economic Research.

The U.S. healthcare and social assistance industries are expected to experience the highest number of job openings and the greatest challenges in filling those positions to meet demand out of all sectors over the next 10 years, according to a report published in April by the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington, D.C.

“We have a workforce that is underpaid and undervalued in many ways, and it's a direct result of our society,” said Bates. “Whether it's due to stigma or lack of understanding, we don't prioritize mental health as a society.”

Seven Hills works with about 100 interns at any given time who provide enormous relief to the organization’s workforce strain, Jordan said. Still, those interns tend to only stay for a couple of years. Though they want to continue working with Seven Hills, some even coming to Jordan with tears in their eyes, the pay gap between nonprofits and the private sectors are indisputable.

“They can go to the state, or most likely, they can go to a private clinic or work on one of the online providers and make $40,000 more,” said Jordan.

Essentially, Seven Hills is training professionals for the private industry, she said. Though Jordan is very happy for her employees who move on to lucrative opportunities, she’s painfully aware of the cracks in services that remain.

“The clinics that support folks on MassHealth, folks with little means, folks who are struggling with those social determinants, we don't have enough clinicians to meet the need,” she said. “That creates wait lists. It creates barriers.”

Central Mass. is made up of 84 cities and towns, many of which do not have equitable access to the care available in Worcester, a city saturated with nonprofits and hospital systems, said Charisse Murphy, executive director at Shine Initiative, a Worcester nonprofit promoting youth mental health awareness.

The August closure of Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer is just one example of this, said Murphy.

“When we talk about something like mental health, if there are people with brains in a particular location, they need services,” said Murphy.

Although the region has benefited from more remote and virtual services since the COVID pandemic, those methods are often not ideal when treating mental health needs.

“There's just a disconnect,” she said.

Moreover, virtual services present their own barriers; access to a phone or computer, to wifi, and to a quiet, private, and safe space to speak openly about mental health is not evenly spread, leaving too many in need behind, she said.

Collaborative approach

“We've been so used to operating in silos, and we just can't afford to do that anymore,” said Jordan.

Collaboration doesn’t mean reinventing the wheel; it can be as simple as a phone call or an email.

Murphy, who has herself coordinated efforts with both Seven Hills and Open Sky, said she works with both organizations from her reaching out to inquire about an available bed or by responding to their requests for specialized services.

“Us as leaders in the community [need to be] aware of what programming is in the city and making sure that if things change, we know about those things,” said Murphy.

One way leaders can stay informed is through quarterly meetings, Murphy said. She focused the first six months of tenure as executive director going around to neighboring organizations and introducing them to what Shine does and the services it provides.

“I do think that there is a level of putting your pride aside and focusing on whatever mission is core to your organization,” said Murphy.

These collaborative efforts are not exclusive to human services providers: police departments, nonprofits, schools, and housing agencies all play a part in mental health care, said Bates.

“No single organization can fix this alone. We need true regional coordination that includes the ability to share data, share the responsibility, where we share outcomes,” he said. “The more we can work on coming together and working across sectors, the better.”

One way the region can do this is by bolstering its co-responder models in which mental health providers accompany police responding to calls for mental and behavioral health crises, said Bates.

Ultimately, the goal is to enhance the region’s preventative mental healthcare services, he said. Those efforts will serve to relieve strains on emergency rooms that continue to house patients needing care for acute mental health needs.

“The best crisis response is one that prevents the crisis in the first place,” said Bates. “We need to shift our mindset from react reaction to prevention.”

Open Sky has a workforce training program created in collaboration with Seven Hills: The Human Services Career Support Program began in 2022 to offer immigrants and refugees access to entry-level roles at both nonprofits.

Collaborations like these not only tackle multiple organizations’ needs at once, but they promote financial stability for individuals and families, directly affecting mental health.

With limited state and federal funds, organizations can often be pulled apart in competition for resources, instead of coming together, said Jordan.

“Part of the issue is we're competing against ourselves,” she said.

Last year, Shine worked with the nonprofit Girls Inc. of Worcester to apply for a grant to create gender-specific mental health services. In December, the two organizations were awarded a joint $50,000 grant from the Andover-based ALKU Foundation, with about a quarter of it going to Girls Inc. Murphy later received feedback from ALKU, saying the fact the nonprofits were working in partnership helped them in the selection process.

“Funding will come and go,” she said. “Outside of the funding, I wanted people to somehow get the message that they have the power.”

Mica Kanner-Mascolo is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the healthcare and diversity, equity, and inclusion industries.