High rates of maternal mortality harm mothers and families

Photo | Courtesy of UMass Memorial Health Care

Jennifer Romanski, a registered nurse at UMass Memorial Health Care, which is adjusting its communication policies to improve maternity outcomes, helps care for a newborn.

Photo | Courtesy of UMass Memorial Health Care

Jennifer Romanski, a registered nurse at UMass Memorial Health Care, which is adjusting its communication policies to improve maternity outcomes, helps care for a newborn.

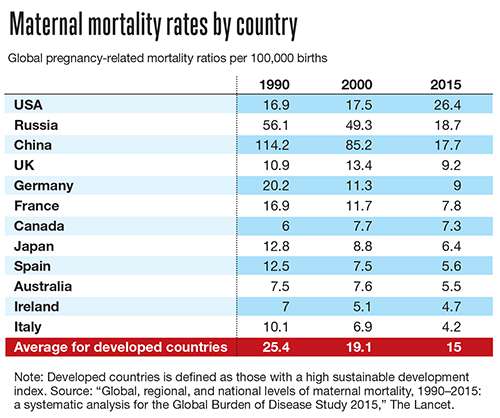

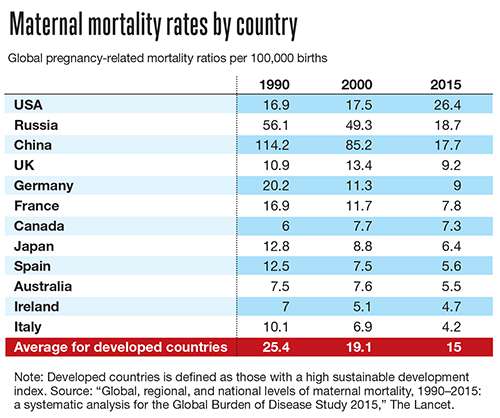

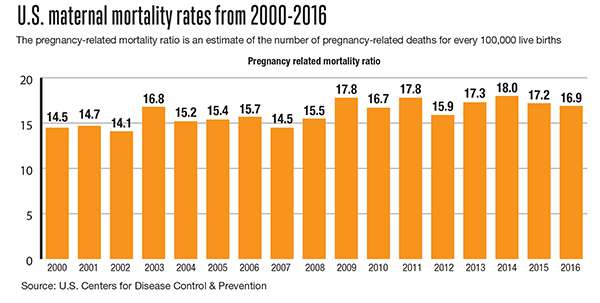

The U.S. has some of the highest maternal mortality and morbidity rates compared to other developed countries.

“What’s particularly striking is that for an American today, you’re 50% more likely to die during childbirth than your own mother was,” said Dr. Neel Shah, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School and director of the delivery decisions initiative at Harvard’s Ariadne Labs in Boston.

However, dying is still not a common outcome during childbirth. Massachusetts itself has low mortality rates in comparison with the rest of the U.S., but it needs to keep working, said Dr. Eugene Declercq, professor at Boston University School of Public Health, who has worked with the Massachusetts’ Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee.

“The concern with maternal mortality is not that it’s really big numbers [from a public health perspective], but rather that it is so eminently preventable. In so many of the causes the death could have been prevented,” said Declercq, “In 2018, that was about 658 deaths, which is less than how many people die of COVID a day. So why the concern? Because it is often something that could have been prevented. Women shouldn’t have to worry about dying while giving birth.”

“Maternal health is a barometer, the bellwether for the well-being of all of us,” Shah said. “If you see moms suffering, it means we’re all suffering. It is the leading indicator in every humanitarian crisis.”

An issue of mortality and morbidity

Mortality is extremely tragic, but is only the tip of the iceberg, said Dr. Julianne Lauring, OB/GYN-maternal and fetal medicine at UMass Memorial Medical Center and assistant professor at UMass Medical School in Worcester.

It is important to extend the conversation to morbidity. Measuring morbidity allows researchers to capture all the preventable difficulties happening during birth, like transfusions and hemorrhages.

“Those happen about 1.4% of the time roughly and count for about 50,000 births per year. When you put it in those terms, you’re dealing with a much larger issue,” said Declercq.

Looking at both allows the data to represent how unequal and insufficient treatment can be.

“Morbidity includes all of those other people who have had something happen to them that they shouldn’t have had,” said Lauring.

For every death, there are hundreds of major injuries and tens of thousands who suffer, said Shah. It is not just deaths during delivery, but deaths caused by factors outside delivery.

“Women need better access to healthcare in general so that they can manage their healthcare morbidities, decide when they want to have pregnancies, be at the optimal weight before pregnancy. All of those things play into this, and those societal issues need to be addressed before the patients even get to us,” said Lauring.

Racism in maternal care

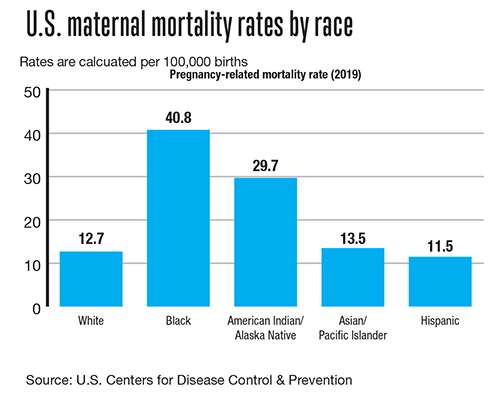

When you stratify maternal mortality and morbidity rates by race, further inequalities become clear and factors outside of the delivery room play a larger and important role.

“When you look at maternal mortality, it is not only people who are dying at the moment of childbirth. Two-thirds of those cases are people who die in the months before and the months afterwards,” said Shah, “What that means is that it’s not only a failure of safe healthcare delivery. It’s equally a failure of social support and the communities where people live.”

Factors of untreated illness, economic disempowerment, and social isolation deeply impact mothers.

“It’s impossible to look at this problem, maternal mortality or the larger issues of maternal health, without seeing it from a racial justice lens,” said Shah.

Black women are 3-4 times more likely than white women to experience maternal mortality and morbidity in Massachusetts. Latina women are two times more likely.

“For Black women in particular, [morbidity] it’s 3-4 times higher in the state of Massachusetts, which is better than other parts of the country but still horrendous,” said Lauring.

There are systematic problems inherent to the U.S. healthcare system even more problematic for people without means and are heightened for people of color, said Declerqc.

Major causes

Leading causes of maternal mortality and morbidity are hemorrhages, high blood pressure, transfusions, infections, and cardiomyopathy, or weakening of heart muscles. The U.S. has the highest rate of transfusion at birth vs. other developed countries, said Declercq.

High blood pressure is a good example of how preventable maternal mortality and morbidity is.

“When bad things happen, like when women have strokes or die as a result of high blood pressure in pregnancy, and [doctors] look back on it, there were hours of potential intervention,” said Lauring.

With Black women, these causes are exacerbated by the reality of how they are treated in the medical system.

“Black women are more likely to note problems with respective care,” said Declercq.

Respective care includes listening to women about what they are feeling and experiencing throughout the process of giving birth and then valuing and acting on those experiences.

“People have goals in labor other than not being injured,” he said. “They deserve dignity in the process too, which a lot of people are not getting.”

As Black women are often treated differently by nurses and doctors, protocols can be ignored or delayed.

“Every patient is different and there is so much variability in medicine, but there is a lot of value to protocols and guidelines, making sure people go with the guidelines first,” said Lauring. “Then if it’s not working, then think about what is making this patient different instead of saying, ‘Well, this patient is different’ right off the bat and not following those guidelines.”

Safer healthcare for mothers

At UMass Memorial Medical Center, the hospital has been adjusting and tightening its evidence-based policies and making sure they are followed for every patient every time while ensuring communication is clear between doctors and nurses. Communication is a key element to addressing maternal mortality and morbidity, said Lauring.

“90% of these morbidities and mortalities, at the end of the day, the root cause is a communication failure and a lack of accountability,” said Shah.

One way Shah and his colleagues are addressing these issues is through the Team Birth Project, aiming to improve safety and dignity in maternal health care. Team Birth Project is based on a simple system: a dry-erase white board across from the mother’s head.

The name of the mother, the names of all team members, the plan, and the next time when the team will get together and talk as a whole group are written on the white board and updated throughout the process. The mother’s preferences are recorded.

This protocol has been tested for two years across the country and found to helps to address major problems, including mothers having a better understanding of what is going on and feeling heard improving mortality and morbidity outcomes.

At UMass, the hospital system is tackling the race components of this issue through the creation this year of an anti-racism task force on the maternity ward. Its goal is to reduce disparities in the maternity ward and to diversify the workforce to be more representative of its patients.

“We’re going to do a bunch of things including training to get people to reduce their unconscious bias, become aware of the systematic racism that exists ... and changing the way we do health care,” said Lauring.

However, in order to create a safer environment for mothers, maternity wards cannot be the only ones doing this work, said Shah.

“It will take the health industry reforming, and it will also take society reforming to value Black lives and to value people who are giving birth and moms differently. Within the healthcare system, there’s a fundamental retraining that needs to happen,” said Shah.

The healthcare system itself needs to be restructured to focus on women’s health and to value women’s health for itself, said Declercq.

“Fundamentally, people deserve more than emerging from childbirth unscathed,” said Shah.

0 Comments