A popular dieting trend today is less about calorie counting or carbs and less about what is being eaten. Rather, it is about when.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

A popular dieting trend today is less about calorie counting or carbs and less about what is being eaten. Rather, it is about when.

Intermittent fasting – eating only between certain hours of the day, or some days much less than others – may or may not be the new Atkins diet, but it’s one being talked about and studied as a new effective way to lose weight.

Of course, just because intermittent fasting is being written about and studied often today doesn’t mean it’s a new concept.

“It’s been around since the beginning of time,” said Dr. Fatima Stanford, an obesity medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Still, there’s little consensus, if any, whether restricting calorie intake between certain hours or days is more effective – or safer – than simply choosing to consume fewer calories every day in general.

A diet that works for someone who’s able to control their cravings if they’re restricting themselves one day but not another could be more effective with one person than another. A diet also needs to be tolerable enough to be maintained for a long period.

“No one diet works for everyone,” said Dr. Vicki Catenacci, an associate professor of medicine in endocrinology, metabolism and diabetes at the University of Colorado.

A new attempt at weight loss

The Atkins diet was a low-carbohydrate fad. The similar ketogenic diet is rich in proteins and fats while shunning carbs. The Paleo diet focuses on lean meats, fish, fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds. The Mediterranean diet revolves more around plant-based foods. Other diets involve foods’ alkaline levels, and others on sugar intake.

Those diets – they might be called fads to some – focused on what a person eats or doesn’t. Intermittent fasting limits when a person eats during a day or week.

A common type is time-restricted eating, which limits someone to, say, a six-, eight- or 12-hour window for all their meals during a day, usually by skipping breakfast. One aim is to eliminate late-night snacking doctors tend to find among the worst habits for maintaining a healthy weight.

Another type of intermittent fasting limits someone’s intake to 25% of a typical day’s calories – so 500 or 600 calories a day – either every other day or every other week. Another, called 5:2 fasting, includes two days of fasting for every five days of normal eating.

Catenucci sees intermittent fasting like other diet trends, or like the idea of eating a bunch of small meals or snacks throughout the day instead of fewer, larger meals.

“But that kind of backfired because each time you eat is an opportunity to overeat,” she said.

Among recent government-funded studies, reviews of intermittent fasting are somewhat mixed. Most find benefits to some people, particularly if fasting spurs the body to switch from using glucose stored in the liver for energy to ketones, which are stored in fat in the body.

Guidance from the National Institutes of Health says in some animals, studies have found fasting diets to protect against diabetes, heart disease and cognitive decline, even slowing the aging process. One potential harm, it says, is an increased risk of gallstones and a higher likelihood of needing surgery for gallbladder removal.

Skepticism from experts

If dietary experts agree on one thing, it’s that no diet works for everyone.

The health website MedPage brought eight specialists together in 2018 to talk about intermittent fasting, with a few key points from doctors: The diet can’t work if it leads to excess intake when someone is eating, and keeping intake to certain hours may not be any more effective than simply eating better in general.

“The main problem with fasting is that it is an unusual and potential awkward way to live when others in your life don’t share the practice,” said Dr. David Katz, the founding director of Yale University’s Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center. “Do you sit at a table and observe while others eat?”

Stanford views intermittent fasting from a long perspective – very long. She looks back to the time of hunters and gatherers, when, without refrigeration, people had to eat in very finite periods of time when they had food available to them.

Fridges, ovens and microwaves, along with preservatives and much else, have allowed us to eat virtually whatever we want whenever we want. People now typically eat throughout a 14-hour period of the day, Catenacci said.

That’s a major cause of the problem.

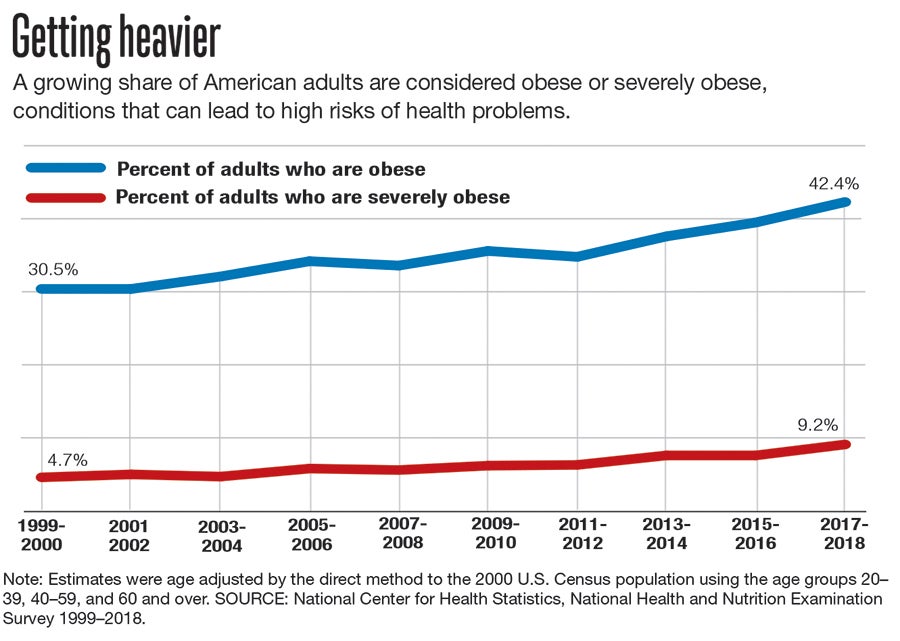

In less than two decades, the rate of American adults counted as obese rose from 30.5% to 42.4%, according to a 2018 study by the National Center for Health Statistics, part of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For those considered severely obese, those numbers jumped from 4.7% to 9.2%.

Those trends aren’t expected to end any time soon.

A study published in December in the New England Journal of Medicine predicted that half of American adults will be obese in 10 years. The rate will exceed 35% in every state, and above 50% in 29 states, the study said. Nearly one in four adults by 2030 will be severely obese.

Massachusetts has the fourth lowest rate of adult obesity in the U.S., according to the CDC, at 25.7%.

With those numbers, Americans may be only more likely to seek out new diets as a way to lose weight.

But Stanford says intermittent fasting isn’t likely to be it because the body likes stability. Intermittent fasting, with long periods of little to no eating in some cases, does not offer stability.

“We like to try this, then we want to try this, but the brain likes stability,” she said.

With that in mind, some participants in intermittent fasting studies end at a higher weight than when they started. Their body wants to maintain a flat weight, she said, even if that weight is too high.

Doctors aren’t fond of the idea of a cheat day either – the idea of someone taking a day off from watching what they eat without much consequence.

“You can undo three days or even a week’s worth of hard work,” Catenacci said.

Needing a cheat day can also be a sign of an unsustainable diet, Stanford said.

“You have to make these things fit into the context of your life,” she said, “or else you can’t sustain them.”