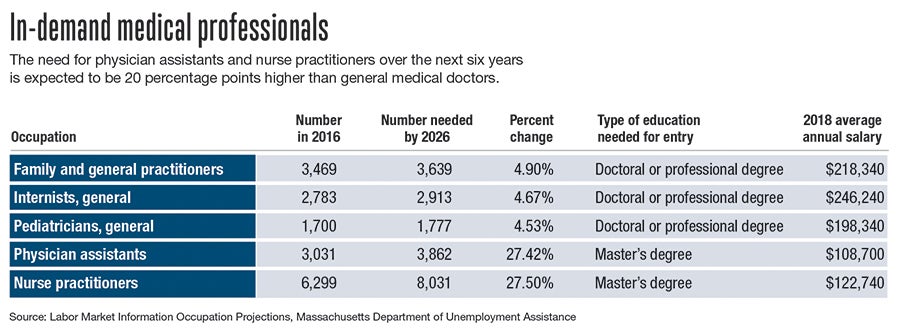

As demands on the healthcare system in Massachusetts rise and physician shortages become a more pressing problem, the state projects rapid growth in demand for health professionals.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

At UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester, Catherine McKinnon works in pulmonary and critical care, diagnosing patients with complex needs, determining appropriate treatments and prescribing medicines. At HealthAlliance Hospital in Leominster, Duncan Daviau works for Wachusett Emergency Physicians, diagnosing and treating patients who come through the emergency department doors for all kinds of reasons.

Neither of them is a physician. McKinnon is a nurse practitioner. Daviau is a physician assistant. Both spent years training to perform many of the same jobs doctors do. As demands on the healthcare system in Massachusetts rise and physician shortages become a more pressing problem, the state projects rapid growth in demand for health professionals like them. But, to fully reach their potential, organizations representing these kinds of workers say, the state must change its laws.

Stephanie Ahmed, a nurse practitioner and legislative director of the Massachusetts Coalition of Nurse Practitioners, said many people wait 100 days or more for a first visit with a family physician or pediatrician. The issue is particularly serious in many parts of Central and Western Massachusetts. Ahmed said nurse practitioners are hampered in their ability to help address this situation because the state requires them to have an official relationship with an overseeing physician.

“When you think about Massachusetts leading the country in health reform, you need to think about that in parallel – that we have the most restrictive nurse practitioner act in the country,” Ahmed said. “So that really hampers the utilization of this workforce.”

MCNP is pushing for legislation known as NP SAVE, which would grant nurse practitioners the same full practice authority they now have in 22 states, including the rest of New England, and Washington, D.C. The bill’s Senate sponsor, Sen. Marc Pacheco (D-Taunton), said the legal change would make it easier for state residents to get needed care while helping keep healthcare costs down.

“Removing outdated and restrictive provisions that are there right now in terms of rules supervising what’s going on with nurse practitioners just is long overdue,” Pacheco said.

However, the Massachusetts Medical Society, the state’s main professional group for physicians, opposes the legal change, saying doctors are subject to different educational and licensing requirements than other providers.

“The MMS believes that the physician led team-based care model promotes integrated, coordinated care that utilizes all appropriate healthcare professionals while ensuring that physicians are available for consultation or collaboration when necessary to promote the highest quality and safety of care for patients,” the organization said in legislative testimony in September.

Pushing for autonomy

McKinnon, who serves as legislative co-chair of the MCNP, said it’s important to note, under current law, physicians don’t have to provide day-to-day oversight of nurse practitioners’ patient visits or prescription writing. In her case at UMass, she said, a doctor simply looks over a record of her prescription-writing and signs off on it.

“I have my own malpractice insurance,” she said. “I am responsible for the care that I provide, for the medications I prescribe.”

The problem, McKinnon said, is the law can limit the care nurse practitioners provide depending choices their physician colleagues make. That’s a particular issue when it comes to medication-assisted treatment for people with substance use disorders, which health professionals see as a key part of fighting the opioid epidemic. Nurse practitioners need 24 hours of intensive training to receive state waivers allowing them to provide MAT, but even after they need approval from their supervising physician.

“This particular type of practice and therapy, it does put demands on a practice,” McKinnon said. “Lots of physicians don’t want to be waivered.”

What that means in practice is nurse practitioners often want to provide MAT but can’t, contributing to a serious lack of resources for people with substance problems, especially in smaller communities.

McKinnon said another problem arises when there just aren’t enough doctors available to act as supervisors for nurse practitioners. In some behavioral health practices, she said, one psychiatrist can be the official supervisor for 15 or 20 nurse practitioners. In one case on the South Shore, she said, a psychiatrist whose collaborating nurse practitioners serve thousands of patients is planning to retire. The practice has not been able to find a replacement.

“Many nurse practitioners will be forced to move their practices to Rhode Island,” McKinnon said. “In one state they’re qualified to provide this care, and in Massachusetts they can’t without a physician.”

PAs waiting for their turn

While the legislation now under consideration at the Massachusetts State House does not include language about physician assistants, Daviau, who serves as treasurer of the Massachusetts Association of Physician Assistants, said their situation is somewhat similar to that of nurse practitioners. He said their licenses must be formally appended to a physician’s license, even though “for the most part, I’m seeing patients pretty autonomously.”

When physician assistants first entered the U.S. health care landscape in the 1960s, he said, they were trained in a certificate-level program and worked under direct supervision of physicians. Today, their educational programs are master’s or even doctoral level. Daviau said he likes the collaborative nature of his practice at HealthAlliance, but the legal structure for the profession is outdated.

“It does create a burden on hospitals to find supervising physicians,” he said. “It’s an administrative burden that slows things down and makes it harder to hire PAs within the state.”

Daviau said MAPA has been disappointed several recent health reform efforts from Gov. Charlie Baker’s office have acknowledged the importance of nurse practitioners and dental therapists – who serve a parallel function to NPs and PAs in the dental health field – without addressing PAs.

“We were kind of left in the dust,” he said.

Pacheco said he supports reforms for physician assistants as well, but in previous years bills addressing both professions haven’t made it through the legislature.

“That has been seen as too much to ask for as it’s gone through the process in the past,” he said. “We figured we would do what most states have done in New England and try to get that on the floor first.”

With the bill going through the committee process now, he said he’s hoping that vote will come later in the legislative session.