Keeping construction working: Long plagued by labor shortages, local construction officials are trying to stem the pain caused by a population drop and Trump’s anti-immigrant campaign

photos | courtesy of Steve Sullivan at Building Mass Careers

Organizations like Building Mass Careers are working to bring more workers into the construction industry but are facing an uphill battle due to demographic changes in the state.

photos | courtesy of Steve Sullivan at Building Mass Careers

Organizations like Building Mass Careers are working to bring more workers into the construction industry but are facing an uphill battle due to demographic changes in the state.

Massachusetts’ population is aging, as Baby Boomers reach retirement age and relatively low birth rates among younger generations have failed to make up the gap. Immigrants have played an important role in making up for this population shortfall, but the expected drastic changes in the number of immigrants entering the country may shut off that supply of workers.

These demographics mean a number of key industries across the state face labor shortages, with future shifts in populations expecting to make the issue an even greater challenge. The state’s labor force is projected to grow 6.7% from 2020 to 2050, less than half the rate of 15% seen between 1990 and 2020, according to population projections from the UMass Donahue Institute.

This labor crunch is particularly concerning for the construction industry and its task to help build the state out of its persistent housing shortage. There’s plenty of work to be done, but not enough workers to do it, said Steven Sullivan, director of workplace development for the trade group Associated Builders and Contractors of Massachusetts.

“We’re one of the oldest parts of the country, so all of our infrastructure is antiquated,” Sullivan said. “We have to do a lot of retrofitting, plus Massachusetts is considered one of the biotech capitals of the world, which takes a lot of piping, electrical, clean rooms, and other construction work. You’ve got to focus on recruiting new faces to the construction industry.”

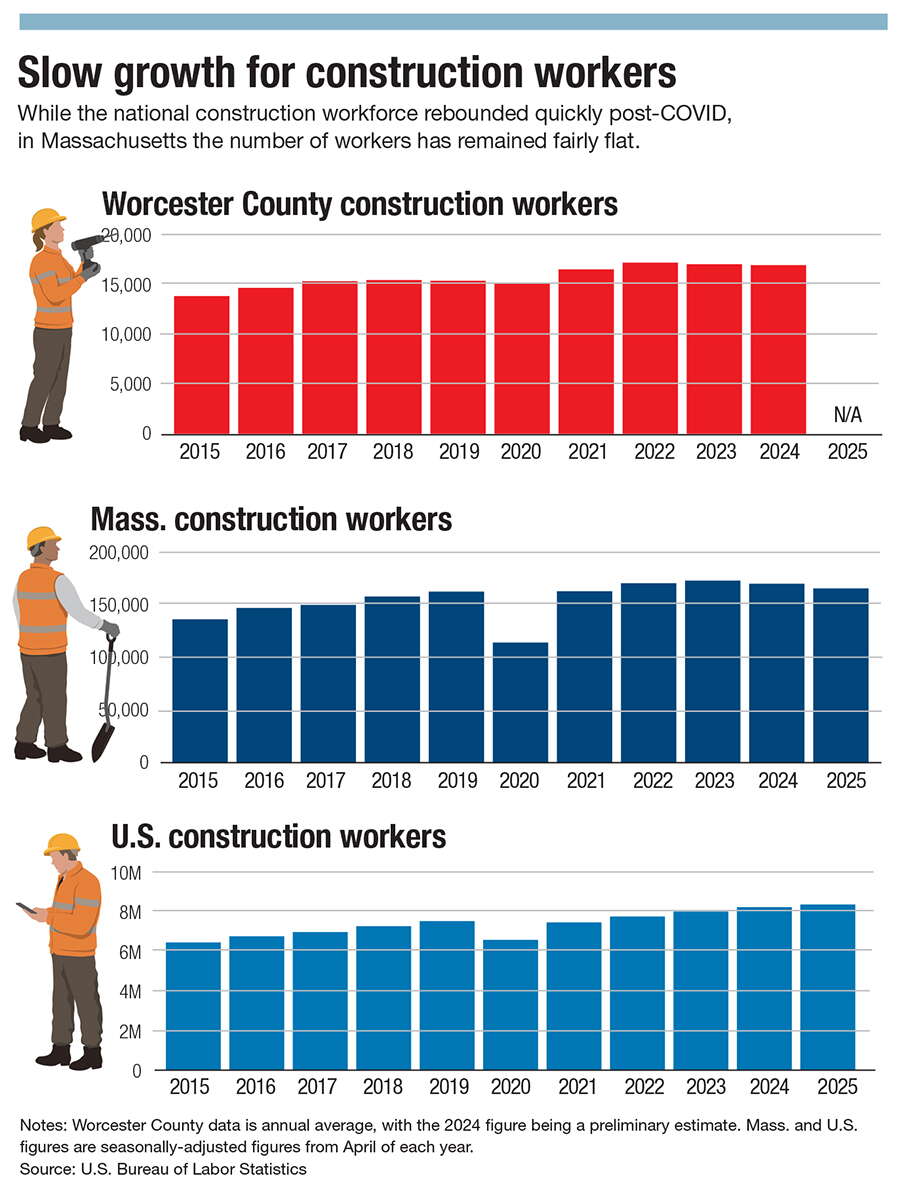

Even though the amount of Americans employed in the construction field has climbed 12.3% since 2021, from 7.4 million to 8.3 million, according to seasonally-adjusted data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, there remains a persistent undersupply of labor in the industry. The construction space must attract almost 500,000 new workers this year to meet expected demand, according to a January report from the Associated Builders and Contractors, a national construction trade association.

In Massachusetts, the industry has not mirrored the national growth in workers and has actually seen a decrease of about 7,400 construction workers since 2023, according to BLS.

Workforce cliff

“It’s something we’ve been committed to for decades, trying to bring people into the workforce and build that workforce up,” said Dave Fontaine Jr., CEO of Fontaine Bros., a large construction firm with offices in Springfield and Worcester. “There’s an aging workforce right now, right along with a lot of blue-collar jobs.”

The issue, which has been persistent in the construction industry since the Great Recession, will get worse, said Sullivan.

“Our industry is facing a workforce cliff,” Sullivan told attendees at a MetroWest Economic Research Center conference held on the topic of the state’s aging population in May. “Many seasoned professionals are retiring, taking with them decades of experience, skill, and knowledge. Frankly they’ve earned it, after years of physically demanding labor. But the void they leave behind is massive. What’s often overlooked is just how foundational construction is to the rest of the economy.”

About 66% of firms report project delays due to labor shortages, according to a 2022 survey by the Associated General Contractors of America. While other factors, including rising material costs, difficulties in raising capital due to high interest rates, and uncertainty created by tariffs are also to blame, the country has seen a persistent increase in the amount of large construction projects falling by the wayside.

The Project Stress Index composite, a metric created by construction software and data provider ConstructConnect to measure the amount of preconstruction projects with delayed bid dates, placed on hold, or abandoned, climbed 11.4% in May to 122.8, compared to a 2021 weekly average of 100.

Trump scaring workers

In addition to playing a key role in making up for the state’s low birth rate, immigrants represent nearly a quarter of employed construction workers and nearly a third of construction trades, according to 2022 data from The Center for Construction Research and Training.

“The Congressional Budget Office did an estimation of what they thought international migration was going to look like in the future,” Denis McAuliffe, research analyst for the UMass Donahue Institute, said during the May MERC conference. “It looks to be coming in at far less than what we're experiencing now and what we have experienced in the past, which could have severe effects for the Massachusetts population.”

CBO’s projections say net U.S. immigration will fall to an average of 1.1 million people-per-year from 2027 to 2055, compared to 3.3 million net immigrants in 2023.

Intense immigration-related rhetoric and enforcement from the President Donald Trump Administration, which has involved both the targeting of undocumented workers and those who have previously enjoyed protected legal status, is already impacting the construction space, Sullivan said. He said a pre-inauguration job fair saw plenty of immigrants in attendance, but one held a short time later drew barely any.

“What’s going on in Washington is scaring them,” Sullivan said. “If immigrants are either not coming into Massachusetts, or if they're already here and they're scared to surface, it's going to be a real problem.”

Another possible federal factor is the Trump Administration's targeting of the Job Corps program, where it has tried to shutter the schools in Grafton and Devens. Job Corps partners with businesses to teach at-risk students the skills necessary to start in-demand careers, such as construction and manufacturing.

“The concept of [Job Corps] is to live on site, learning and immersing into the industry,” Sullivan said. “To lose that, I think that's just terrible. It's unfortunate. It's gonna be a huge void in the recruitment process.”

Beyond pushing back against the complete elimination of Job Corps, Sullivan sees reform of construction ratios, which govern the ratio of apprentices to journeymen on job sites, as a key to bringing younger workers into the fold.

“It’s not cost effective, and it keeps people out of the industry,” Sullivan said of rules in particular situations which require three journeymen per one apprentice. “Have you ever walked down the halls of a hospital and seen three or four doctors with one resident? That’s what it is in construction.”

Overcoming preconceptions

Apprenticeship goals, like the 10% goal set by the City of Worcester, are a step in the right direction, said Elizabeth Wambui, director of diversity, inclusion, and community impact for Fontaine Bros.

Efforts like Building Pathways, a Boston-based nonprofit focused on recruiting and retaining underrepresented groups in the construction industry, are having an impact in attracting people to address workforce shortages, she said.

“We need to encourage everyone to make sure that we are consistently bringing in folks, certainly to meet the goals, but also once you get people in the door, making sure we're keeping them,” Wambui said.

Busting young people’s preconceived notions about construction is a key part in attracting the next generation of workers, said Fontaine.

“Some people look at the industry and don't necessarily see that there's mobility beyond the kind of journeyman career in the trades,” he said, “We try to educate people that you can come into the trades as a laborer or a carpenter, and you can rise to the management level, so there's not always the requirement to just be working with your hands for the rest of your life.”

Another important fact to drill home to prospective youth is the impact of emerging technology on the field, making brains just as important as brawns.

“We’re leaning into technology across our projects, which I think makes it more interesting,” Fontaine said. “A lot of workers are using hammers and screwguns, but they're also using lasers and survey equipment out there. So we try to showcase that at some of the career fairs.”

One benefit of large projects, like the now-completed construction of Worcester’s new Doherty Memorial High School, is they introduce prospective workers to the realities of modern construction and allow for one-on-one interactions with tradespeople, Wambui said.

“We ask our project partners ... to help with these workforce efforts,” she said. “With the Doherty High construction, through the project we were hosting a lot of career fairs and tours. We were able to draw a couple of folks from all that activity, who ended up joining the carpenter’s union. The challenges are there, but for all of us involved in this, we have to work together.”

Eric Casey is the managing editor at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the manufacturing and real estate industries.

President Trump does NOT have an anti-immigrant campaign. He has an anti-illegal alien campaign. Big difference. Words mean things.

1 Comments