When old age comes and aches and pains and other ailments pop up, seniors have a seemingly unending list of prescription drugs to turn to.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

When old age comes and aches and pains and other ailments pop up, seniors have a seemingly unending list of prescription drugs to turn to.

For a number of doctors who’ve studied the issue, that may be exactly the problem.

Studies are showing seniors are much more likely to take a prescription drug – and even to take five or more. That’s raised alarms over seniors taking too many drugs, leading to more common cases of adverse side effects or even what’s known as the prescribing cascade, when one drug needs to be prescribed just to address a side effect of another drug.

Doctors can struggle to find the balance, and they don’t always handle the complexity well, said Dr. Gary Blanchard, a geriatrician at Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester.

“At times, it’s an impossible balance,” Blanchard said. “Sometimes the right thing is to watch things and not introduce things that may be harmful.”

With an aging population combined with the potential negative effects of taking multiple medications, further study is needed to find the right balance, a 2015 National Institutes of Health-funded report said.

More than 1 million Massachusetts residents are 65 or older, according to a 2017 U.S. Census Bureau estimate. That’s about 14% of the population, and a 13% rise in a five-year period.

The Lown Institute, a Brookline nonprofit, called over-prescribing of seniors an epidemic in a report last April. Over the last decade, those 65 and older have been hospitalized for serious drug side effects about 2 million times, the group said.

“The bottom line is, they know how to prescribe … They don’t know how to de-prescribe,” said Shannon Brownlee, the Lown Institute’s senior vice president, addressing the issue of having a patient wean off a drug.

A spike in prescribing

Seniors have long had higher rates of taking multiple medications, but in the past decade or more, usage has spiked.

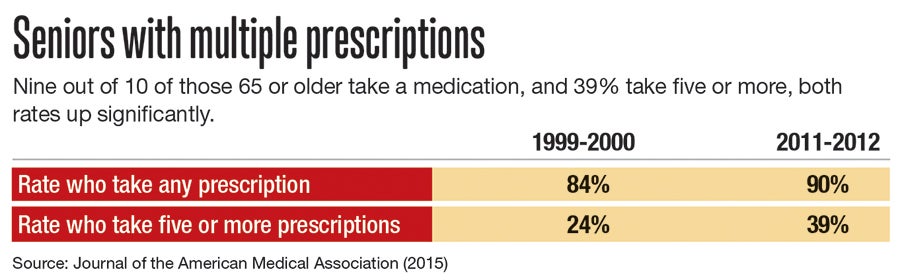

In 1999 and 2000, 84% of seniors said they took a medication, according to a 2015 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association. By 2011 and ‘12, it was 90%.

Those taking five or more prescriptions rose even more during that time: from 24% to 39%.

Among men over age 80, half reported taking five or more medications by 2010, rising nearly fivefold since 1988, a 2015 study in the Journals of Gerontology found.

If trends continue, according to the Lown Institute, medication overload will be responsible for at least 4.6 million hospitalizations between 2020 and 2030 – and cause an estimated 150,000 premature deaths.

“It’s a relatively significant problem when 40% of those over 65 are taking five or more drugs,” Brownlee said. “We also know it’s a big problem because it’s getting bigger.”

Harmful side effects can be different – and more severe – in older adults than younger ones.

A medication that may have worked well in patients’ 60s may no longer once they’re in their 80s. One medication might be needed just to deal with another medication’s side effects, such as an upset stomach or dry eyes, in what’s called a prescribing cascade.

Adverse drug events occur in 15% or more of older patients presenting to offices, hospitals, and extended care facilities, according to a 2013 study in the journal American Family Physician.

Kidneys, which process most drugs through the body, decline in function as we age, Blanchard said. A bad drug interaction or side effect leaving someone feeling groggy or disoriented could be more easily mistaken for a different ailment or simply a bad sign of aging.

If an older patient becomes especially affected, it could even lead to a more major physical impairment.

“You could fall and break your hip,” Blanchard said. “It could affect your cognition.”

Brownlee sees a few causes for the spike in prescriptions: Medical specialty associations too often see prescribing a drug as a first course of action, doctors who may not know all the medications a patient is taking, and a pharmaceutical industry pushing more products and marketing heavily to doctors.

Health companies spend nearly $30 billion a year on medical marketing, with two-thirds geared toward persuading medical professionals – not consumers – of a drug’s benefit, a January 2019 Journal of the American Medical Association study found. That rate of marketing toward doctors has actually fallen since 1997, the study found, but not total spending, which nearly doubled in that time.

Too often, drugs are prescribed for seniors as a preventative measure instead of in response to a condition requiring it, said Brownlee, a former visiting scientist at the Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, an industry group, didn’t return a message seeking comment.

Learning to de-prescribe

A few signs show at least a growing recognition older adults may be prescribed too many pills.

An industry group based in Philadelphia called Choosing Wisely was formed in 2012 with a mission of avoiding care not supported by evidence, not truly necessary and not duplicative of other tests or procedures. The group regularly posts tales of doctors and medical groups committed to those goals.

The U.S. Deprescribing Research Network, funded by the National Institute on Aging, works to develop and disseminate plans for how to de-prescribe – that is, slowly taking a patient off a drug.

When Blanchard was a practicing fellow, de-prescribing wasn’t even a term, he said. Now it’s commonplace.

There’s an alternate step prescribers can take instead of turning to a prescription pad: suggesting a better diet or more regular exercise. But those suggestions may be not be received as well by a patient who might not have the desire or ability to take a more challenging path, Blanchard said.

“It becomes easy to add medications,” he said, “but it’s much harder to subtract it.”

Sometimes, Blanchard said, even something less tangible such as yoga may be the answer. But that’s a challenge when too often a patient will see a doctor’s visit as productive only if something is prescribed.

“We all, as a system, have to find new ways to do this better,” Blanchard said.

Brownlee isn’t encouraged prescribers will reverse course soon.

“The fact that the problem keeps getting worse and worse and worse says that not enough clinicians are aware of it or capable of doing something about it,” she said.

But the Lown Institute has recommended a series of actions, including a potential requirement from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration about drug advertising quantifying both potential benefits and harms.

The institute sees a need for better awareness in both prescribers and patients, more available information on the issue, and better coordination among providers when a patient is switching doctors.