After closing key facilities and operating on mere hours of cash, the Family Health Center of Worcester is in a more stable financial position, in part due to higher insurance reimbursements.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Tensions ran high in an October meeting of the Worcester City Council’s standing committee on public health and human services about the status of Family Health Center of Worcester.

The meeting came after the announcement of 35 layoffs, furloughs, the closing of FHCW’s Webster and Southbridge locations, and at a time when the center’s cash budget was operating on mere hours of reserves. Staff from the health center spoke about concerns, highlighting a lack of confidence in the center’s continued ability to provide quality care if circumstances did not change.

“We are very concerned now that people's trust is not there,” Jennifer Moffit, perinatal services manager, said in the Oct. 12 meeting. She cited the layoffs as disrupting staff retention and morale, and a decreasing ability to invest in patients.

Moffitt said she was not sure FHCW had the 120 days that leadership was proposing as time to implement its plans for improvement.

The center did make it through the 120 days, and now after the conclusion of FHCW’s “Better Together” go-forward plan, some particular painpoints have been addressed and a way onward appears tenable, though some communities remain jilted.

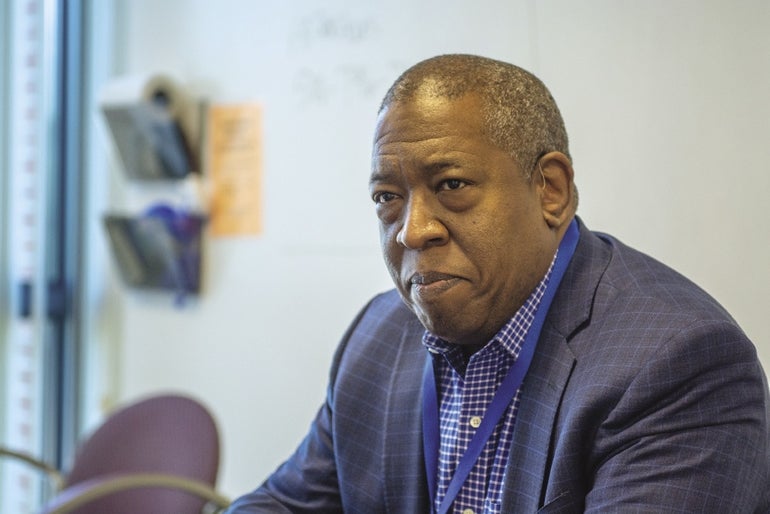

“We’ve been able to move from on the edge to off of it,” Lou Brady, FHCW’s president and CEO, said in a May interview with WBJ.

A place for those most in need

The role family health centers play in a diverse community like Worcester is essential. FHCW saw 27,000 unique patients in 2022, according to the final “Better Together” report.

“Family Health Center is a really vital asset to our city,” Worcester District 4 city councilor Sarai Rivera said in the Oct. 12 meeting. Rivera was critical at the time of the center’s issues with staff. She was not available to be interviewed for this article.

Patients at FHCW are often refugees, people dealing with addiction issues, homelessness, chronic conditions like HIV, and other co-occurring illnesses. Patients with a wide variety of cultural and linguistic barriers use FHCW’s services. Susan Sleigh, chief operating officer at FHCW, said people who speak more than 60 different languages come to the center seeking healthcare services.

“The complexity of needs coming through the door never ceases to amaze me,” Dr. Robert Zavoski, FHCW chief clinical officer, said in an interview with WBJ.

Federally qualified health centers, like Family Health Center of Worcester, exist to provide care for underserved populations. At FHCW, health care is provided regardless of a patient’s ability to pay.

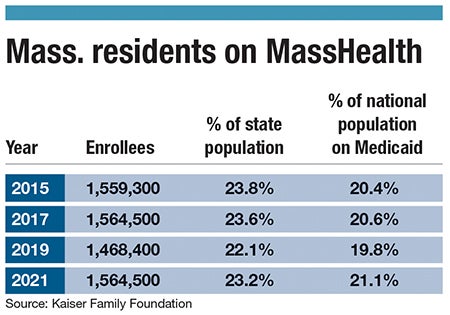

How that works in practice is through a combination of federal grants, Massachusetts Department of Public Health dollars, and revenue from billing insurance, including government insurance like MassHealth, which is the Massachusetts version of Medicaid.

A priority at FHCW is getting more patients insured, said Sleigh, which is why booths near the entrance of the center are set up to assist patients who are eligible to enroll for affordable care insurance, essential to the revenue at FHCW, which is made up of 60% billing for services and 40% in grant funding, Brady said at the Oct. 12 meeting.

New billing rates, which became effective in January, have meant FHCW can charge more to insurance, increasing its revenue for services provided, Brady said.

“We were always doing the right thing,” in providing care, said Zavoski, “and now we are being paid for it,” he said.

The improvement of insurance billing, from 58% to 85%, is one of the primary achievements listed in the post-120 day report. The others are a cost-of-living increase for all staff, the hiring of 10 providers and onboarding of an additional 38 staff members, and the hiring of a new financial team allowing for the maintenance of a 30-day cash-on-hand reserve, according to the report.

Challenges remain, however, particularly as related to the closing of the center’s locations beyond its hub at 26 Queen St. in Worcester.

Left behind in Southbridge, Webster

FHCW has no plans to reopen the closed Southbridge or Webster services, Brady said, as leadership focuses efforts on strengthening the main facility’s operations. Shuttle services from those locations to Worcester are provided to bridge the gap, Brady said.

“We have wanted to be in Southbridge for a very long time, and we still want to be in Southbridge,” Brady said.

Residents of the town, though, may be less eager to welcome FHCW back.

The town feels abandoned by the center, said David Adams, vice chair of the Southbridge Town Council. The “Better Together” report lists a statistic that 87% of staff are optimistic about the future of FHCW, but that kind of optimism is not what Adams said residents in Southbridge are feeling.

“They’ve lost trust. We really don’t want them back in our town at all,” he said.

The frequency of the FHCW shuttles is an issue for people in Southbridge looking to get to Worcester, Adams said, citing complaints received by email from users of that service. Patients who use are often left with no option but to spend the day in Worcester, he said.

“We’re slowly recovering on our own,” Adams said.

From the FHCW leadership team’s perspective, too, there are still areas for improvement.

“We have seen our infrastructure fall behind,” said Brady.

Modernizing that infrastructure and updating the center’s emergency medical records system are two top priorities. The third, listed in the report, is recruiting and retaining staff, a challenge at FHCW and across the healthcare system, an issue predating the coronavirus pandemic.

“Recruitment = revenue,” the report says, asserting its move to pay current and future employees higher, market-rate wages, will make it competitive in recruiting new staff and in turn enable a revenue-generating model, rather than a dollar-hemorrhaging one.

“We have a long history of saying, ‘Yes,’” said Sleigh. “The goal has been meeting the most critical needs of the highest need patients.”

The goal now is continuing to meet those care needs while moving forward.

“We’re not going anywhere,” said Zavoski.