Struggling to pay for drugs

PHOTOS/Matt Wright

Laura Ricci from Sterling must pay $1,200 for one of her prescription medications.

PHOTOS/Matt Wright

Laura Ricci from Sterling must pay $1,200 for one of her prescription medications.

Every couple of months, Laura Ricci purchases three different medications at her local pharmacy, preventing her from having a seizure. The Sterling resident was diagnosed with epilepsy in 2005 and lost her driver’s license shortly after.

After mixing and matching different prescription medications over the years, her physicians, in 2013, found the right combination of pills to ward off her symptoms. But while these prescription drugs have allowed Ricci to get back her driver’s license, prevent seizures, and reclaim a normal life, her trip to the drugstore is filled with stress and anxiety.

“The hairs on my neck stand up,” Ricci said.

That’s because one of those medications she needs is a drug called Vimpat. There is no generic option for the medication, and so it costs Ricci $1,200 to purchase.

“I tried to get off that medicine, but I ended up having nerve issues on my face,” Ricci said. “It was impossible to get off. I need it.”

Vimpat is produced by Florida-based L3Harris Technologies, which reported $6.8 billion in revenue for fiscal 2019, a 10% increase from the previous year.

The cost of pharmaceutical drugs has far-reaching impact to Massachusetts residents beyond just Ricci, whether they’re paying for prescription drugs or not.

Ricci’s son Dominic was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes when he was 8 years old. Now in college, he relies on insulin to live.

“It’s like air to him,” Ricci said.

Dominic is on MassHealth, but Ricci estimates between the insulin, the pumps, the test strips, and glucose monitors, it costs the state $25,000 a year to supply her son with the life-saving medication. That expense is ultimately passed onto the taxpayer.

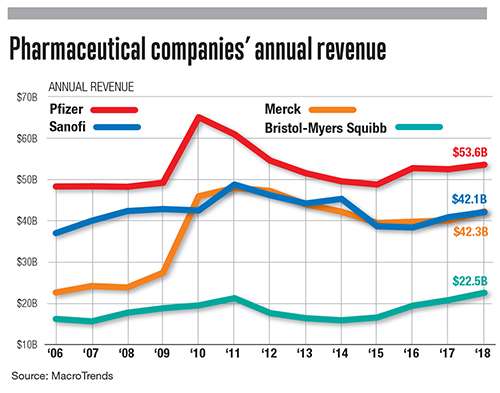

The Massachusetts Health Policy Commission – an independent state agency examining healthcare spending and payment models – said in its 2018 cost trends report Massachusetts drug spending increased more than 4% last year, while total spending across the healthcare system went up by 1.6%.

Additionally, according to Alyssa Vangeli, co-director of policy and government relations for Massachusetts advocacy organization Healthcare For All, drug spending in MassHealth has nearly doubled from $1.1 billion to $1.9 billion over the past five years.

Proposed changes

Gov. Charlie Baker, as well as healthcare advocates across the state, is proposing legislation to curtail prescription drug prices and allow the state more power to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies.

“This legislation addresses the drug affordability issues,” said Vangeli. “Too many people are skipping medications and don’t have access to the drugs they need.”

A poll from Washington, D.C. public opinion survey firm PerryUndem showed 36% of Massachusetts voters said they or a family member haven’t taken medication as prescribed because of high drug prices. This includes taking less or skipping doses, not filling a prescription because of cost, cutting back on other household expenses to pay for medication or sharing medication with someone else.

In addition to Baker’s proposal, legislation from State Rep. Christine Barber (D-Somerville) and State Sen. Jason Lewis (D-Winchester) focuses on prescription drug costs and affordability.

Combined, these efforts are focused on providing cost transparency and allow MassHealth to negotiate with drug companies for lower prices. These proposals look at expanding the role of the HPC, which currently does not have any say in pharmaceutical prices, to allow the organization to set payment limits for overpriced drugs.

Understanding where the increases come from

Pharmaceutical companies acknowledge drug prices in the state and across the country are too high.

“We understand too many patients are struggling to afford their medicines, which is why we support proposals – like ensuring rebates and discounts provided by biopharmaceutical companies to middlemen in the supply chain are shared with patients at the point of sale,” said Tiffany Haverly, director of public affairs for PhRMA, a pharmaceutical lobbying firm.

“While we’re committed to working toward commonsense solutions to expand access to and increase affordability of medicines, we encourage legislators to keep the industry’s huge economic impact in mind and reject any proposal that would put those jobs and the investment in innovation they represent at risk,” Haverly said.

Haverly said the focus of the conversation spends too much time on the list price, or the price a drug manufacturer initially sets for a medication. Instead, the focus should be on the net price – the amount of money a pharmaceutical company receives – which tends to be lower.

According to Sanofi, which acquired the Cambridge-based Genzyme in 2011, the list price for its medication has risen by 4.6%, while the net price Sanofi has received by health plans declined by 8%.

Sanofi spokesman Nicolas Kressmann said the discrepancy is even worse for Lantus – Sanofi’s most prescribed insulin medication. The net price for its insulin has declined by 30% since 2012, yet out-of-pocket costs for those who have private insurance and Medicare has risen by 60%.

“Focusing on list prices alone will not be sufficient to solve this problem,” said Kressmann. “The solution to drug pricing must include protections for patients, tying responsible pricing to both access and affordability.”

The proposed Massachusetts legislation would target a number of aspects of drug pricing, which could lead to less money for pharmaceutical companies.

“I don’t think these proposals would harm the industry,” Vangeli said. “Most of these companies have a 22% profit margin. Pharmaceutical companies should be able to make a profit, but maybe just a little less of one.”

0 Comments