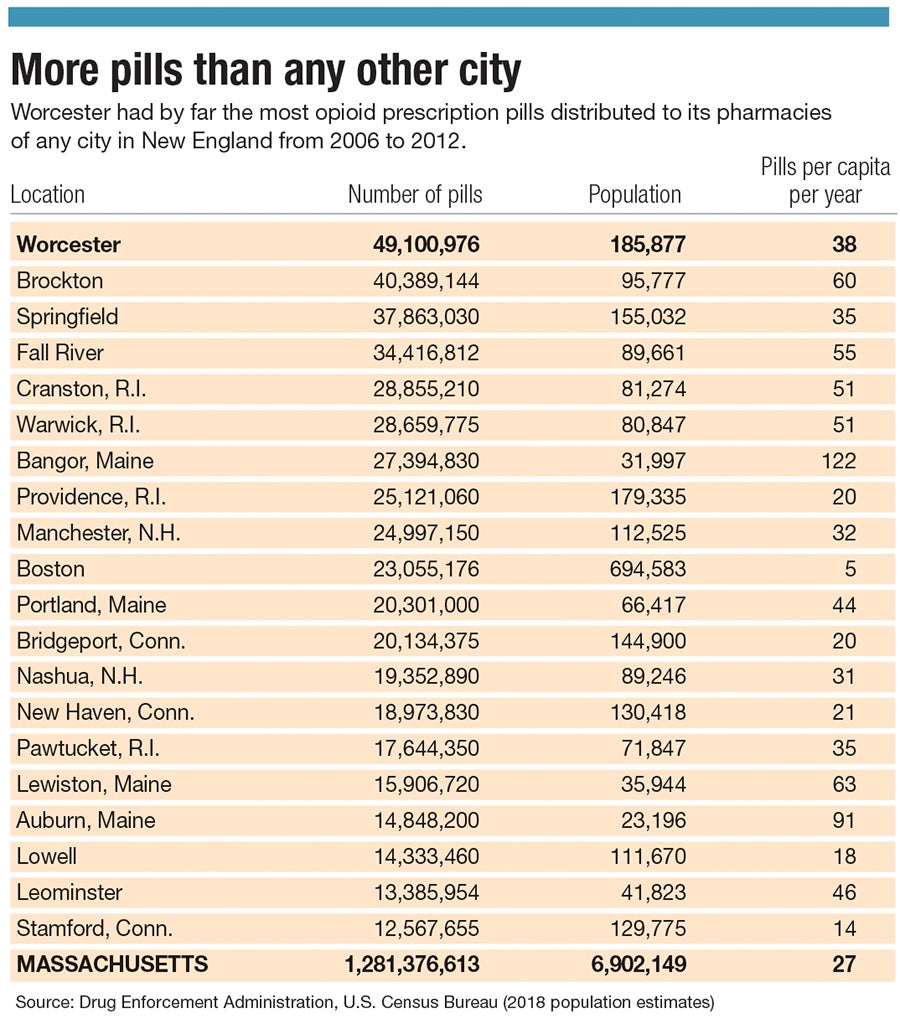

In the years just before the number of opioid-related deaths skyrocketed in Massachusetts and the nation, Worcester became the opioid painkiller capital of New England.

More than 49 million opioid painkillers – Oxycontin, Vicodin and others – were distributed to Worcester pharmacies in a seven-year period ending in 2012, far more than any other city in New England, illustrating how many opportunities there were for addiction in the years just before opioid deaths spiked.

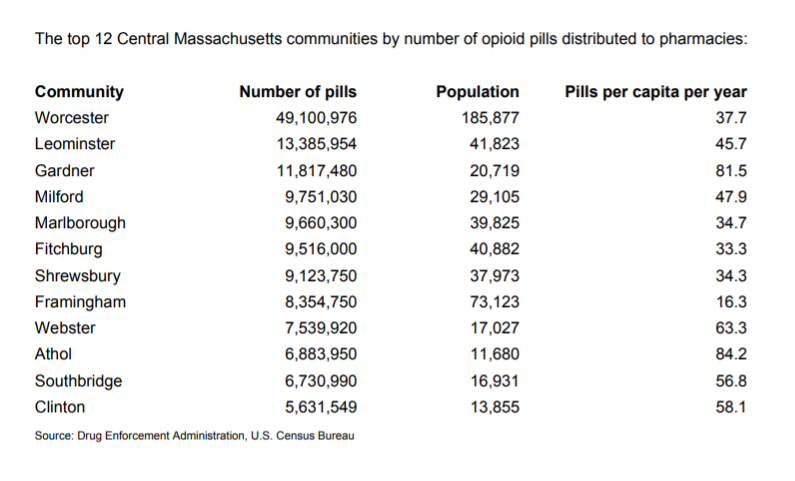

Surrounding areas also had high rates.

More than 190 million prescription opioid pain pills were distributed in Worcester County over that same seven-year period, enough for 34 pills per person per year, according to newly released U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration data that for the first time shows exactly where millions of addictive prescription pills were distributed in communities across the country.

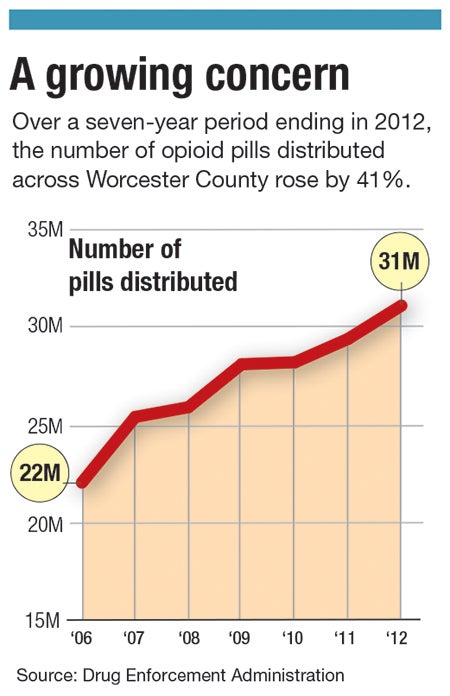

Across Worcester County and in the city of Worcester itself, the number of opioid pills distributed rose by 41% from 2006 to 2012.

Those pills flooded into the Worcester area and elsewhere long after opioid addiction risks were well known but before deaths soared, which could lead to questions of how much local prescribers were culpable in signing off on so many pills that led to an addiction crisis.

“We know the trend was to use pain medications for pretty much everything,” said Romas Buivydas, the vice president of clinical development for Worcester’s Spectrum Health Systems, an addiction treatment provider where 72% of all admissions in the past year were opioid-related. “Now we know there’s an inherent danger of addiction.”

Worcester had easily the most distributed opioid pills of any city in New England, and more than four times the amount prescribed in Boston proper.

Statistics in Athol and Gardner, two small cities in northern Worcester County, are even worse.

Athol, a city of less than 12,000, had nearly 7 million pills distributed to its pharmacies during that period – enough for 84 pills each year for every man, woman and child.

Gardner, with city of less than 21,000 people, had nearly 12 million opioids – enough for 82 pills each year per resident.

Rate of prescription opioids per capita tripled the state rate in those cities. In Worcester, it was 37% greater than the state average, and in Leominster, it was 72% higher.

Worcester County was fifth highest in Massachusetts for the annual rate of pills prescribed per person among the state’s 14 counties, according to the DEA data, which was published by The Washington Post in July following a lawsuit it filed with a West Virginia newspaper, the Charleston Gazette-Mail, to gain access to the records.

Numbers everywhere may be higher: The DEA data of shipments of oxycodone and hydrocodone pills account for three-quarters of the total opioid pill shipments to pharmacies, The Post said. Codeine, methadone, suboxone and fentanyl are not included in the database. The number of pills given to patients is not disclosed, nor are the names of the healthcare providers prescribing the medications.

Risks were known

Opioid painkiller addiction risks were widely known well before the period for which the DEA data is now available.

In 2001, the DEA urged Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, to limit how it marketed and distributed the drug. The agency said then no prescription drug in the prior 20 years had been so widely abused so soon after its release. OxyContin was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1995, with the FDA later saying it wasn’t fully aware that crushing or snorting the pills would lead to widespread abuse.

That same year, theft of OxyContin pills began making headlines, including one case in which masked gunmen robbed a Boston store for the pills.

For years starting in the 1980s, though, providers were trained as seeing pain as a so-called fifth vital sign – along with temperature, pulse, respiration and blood pressure – said Robert Ready, the associate chief nursing officer at Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester.

“If a patient said they had pain, we treated the pain,” Ready said. “This culture was built and educated in the medical and nursing community and is well evidenced in the medical and nursing textbooks.”

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warns prescribers against addiction risks with opioid medications.

The CDC advises doctors opioids are not the first option or routine therapy for chronic pain, and patients should be advised of addiction risks before starting use and periodically during use. The agency cautions prescribers to avoid extended-release pills and when opioids are prescribed for pain, doctors should give patients no more pills than what’s needed.

Deadly crisis

The federal data shows in new detail how much legally obtained opioids contributed to a health epidemic that has killed 2,000 people in Massachusetts each of the last three years. Numbers peaked with 2,100 confirmed opioid-related overdose deaths in 2016, with a 3% drop over the two years since. In 2018, there were an estimated 2,033 opioid-related deaths.

But in Worcester, deaths rates have never come down. Fatalities in the city hit 97 in 2018, up from 80 the prior year and 24 in 2012.

The federal prescription opioids data doesn’t capture more recent years, when those deaths in Massachusetts and elsewhere have peaked.

In 2006, when the first year of opioid prescription data is available, 660 opioid deaths were recorded in Massachusetts. A decade later, it was 2,100.

By 2017, Massachusetts had the sixth highest rate in the country for opioid deaths as a share of the population, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, with 28.2 deaths per 100,000 people. The national average was 14.9.

Pills flood Worcester neighborhoods

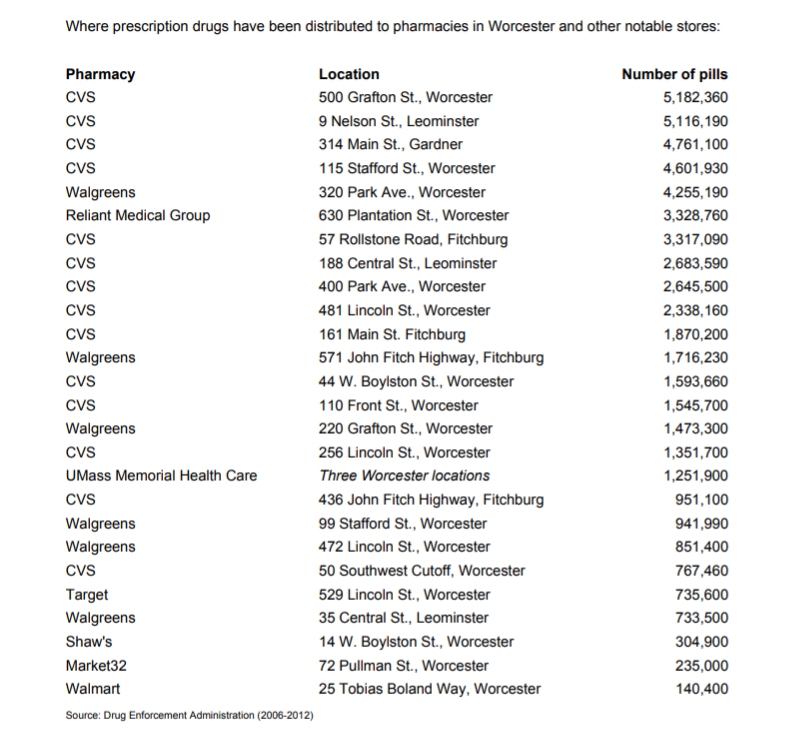

In Worcester, it’s easy to see where tens of millions of prescription opioid pills make their way into the city’s neighborhoods.

In the span of one mile on Park Avenue, more than 4.2 million opioid pills were distributed to a Walgreens from 2006 to 2012, according to the federal data, and more than 2.6 million to a CVS.

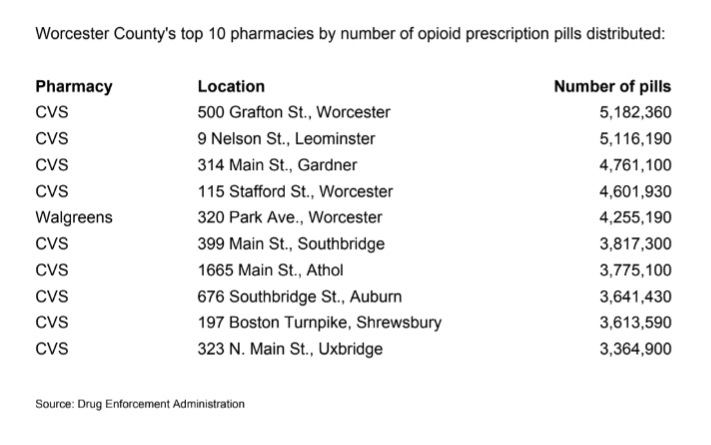

A CVS at 500 Grafton St. had the most opioids distributed in Worcester County and the seventh most in Massachusetts over that time – almost 5.2 million – and a Walgreens just over two-thirds of a mile away on the same stretch filled nearly 1.5 million.

A CVS on Stafford Street recorded more than 4.6 million opioid pills on one side of Heard Street, while a Walgreens on the other side of Heard Street had more than 940,000.

Other areas in Central Massachusetts had high numbers, too.

A CVS on Nelson Street in Leominster reported 5.1 million opioid pills during that seven-year period, and another on Rollstone Road in Fitchburg reported more than 3.3 million.

Those pharmacies had some of the highest number of pills across the state during that seven-year period. Worcester had three of the state’s top 11 pharmacies as measured by the number of opioid pills prescribed. A Leominster CVS had the seventh most, and a Gardner CVS the eighth most.

Even as opioid painkillers have been so widely prescribed in Massachusetts – nearly 1.3 billion during the seven years ending in 2012 – the county numbers here are far lower than other parts of the country. The highest rate in New England was Penobscot County in northern Maine, with 56 pills prescribed per person annually. In some counties, particularly in Appalachia, pills-per-person rates exceeded 100.

Controlling the crisis

Tighter prescription monitoring regulations in Massachusetts have been said by state officials to be partly responsible for the slightly better fatality figures.

Those restrictions have led to a 38% drop in the number of opioid prescriptions in the first quarter of 2019 compared to a year prior, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health said in May. Providers under the Massachusetts Prescription Monitoring Program registered nearly 1.9 million searches in the first quarter in an indication of thorough oversight, an increase of roughly 90,000 since the previous quarter.

The Massachusetts Prescription Awareness Tool, known as MassPAT, allows prescribers to view a patient’s prescription history as a way to identify abuse or prompt early intervention.

The state has also instituted since 2016 a seven-day supply limit for first-time patients, and a requirement for prior authorization for higher dosage amounts and for any doses of methadone, which can be used to treat addiction.

Among other state initiatives, the Massachusetts Consultation Service for the Treatment of Addiction and Pain, a peer-to-peer resource for prescribers, is meant to provide guidance for managing patients’ opioid use.

Some signs exist that over-prescribing is still taking place.

Last November, U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts Andrew Lelling sent letters to an unspecified number of prescribers who were found to have prescribed opioids to a patient within 60 days of that patient’s death or to a patient who subsequently died from an opioid overdose. The letters reminded prescribers of laws against prescribing opioids without a legitimate purpose or in excess quantities.

Worcester County District Attorney Joseph Early Jr. lauded the state’s better prescription monitoring but said more care still needs to be paid to keeping opioids in as few hands as possible.

“Sometimes it’s just one pill” that can get someone addicted, Early said.

Now, Early said, public officials and their healthcare partners are focused more on fentanyl.

“We’re seeing a big increase in fentanyl, a big increase in heroin. It’s cheaper, more easily found,” Early said. “It’s a very complex disease, and it’s going to require a very complex solution, and that’s all of us working together.”

The Massachusetts Medical Society, a group advocating for physicians and medical students, helped develop the state’s opioid prescribing guidelines and has worked to offer provider education and support the state’s prescription drug monitoring program, said Maryanne Bombaugh, the society’s president.

“It is our belief that the practice of medically appropriate prescribing of opioids will continue in this trend,” Bombaugh said.

CVS, responding to the new opioid data, says its market share of opioid prescriptions dispensed is significantly less than its market share during the years covered in the DEA database and since. Opioid pills were a very small percentage of total prescriptions, the company said.

Walgreens said it has also tightened its own distribution of such medications, ending distribution of controlled substances in 2014. Before then, it distributed only to its own chain of pharmacies. It still allows the filling of prescriptions at its pharmacies.

“Walgreens pharmacists are highly trained professionals committed to dispensing legitimate prescriptions that meet the needs of our patients,” the company said in a statement. “Walgreens has been an industry leader in combating this crisis in the communities where our pharmacists live and work.”