Central Massachusetts is projected to have among the biggest shortfalls in the number of available beds in the country, virtually no matter how hard the coronavirus pandemic hits.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Central Massachusetts is projected to have among the biggest shortfalls in the number of available beds in the country, virtually no matter how hard the coronavirus pandemic hits.

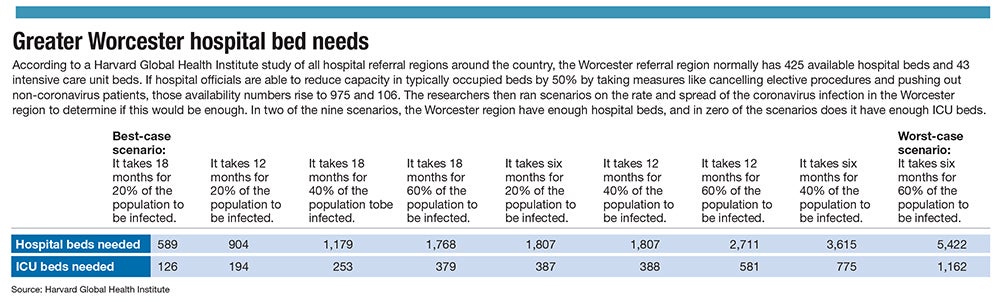

Under nine pandemic scenarios ran by a Harvard Global Health Institute study in March, the number of typically available beds in Worcester hospital referral region – which includes much of Worcester County – would fall short in all nine scenarios. If the region is able to slow the rate of the pandemic and hospitals can free up half of their normally occupied beds, then the Worcester region would have even space in the two best-case of the nine scenarios, although it would still fall short in the number of intensive care unit beds.

The projected shortfall has left local health officials working to empty their beds of non-coronavirus patients and find new ways to get more beds into hospitals, while public officials are looking for alternative spaces, including a plan to put 150 to 200 beds in Worcester’s DCU Center.

“Right now, there's plenty of capacity at the hospitals,” City Manager Edward Augustus said. “This is trying to be ahead of the curve should it be necessary.”

However, even if the Worcester region is able to free up 50% of its normally occupied hospital beds of non-coronavirus patients (and thus increasing the number of available beds to treat coronavirus), the Harvard study still puts the region among the worst in the country for beds shortages: the bottom 13% for all hospital beds of the 305 regions studied nationally, and the bottom 16% for ICU beds.

The best- and worst-case scenarios

The Harvard study looked at every hospital referral region in the country and developed different scenarios based on the region’s ability to flatten the curve: how much of the population is ultimately infected with coronavirus and how long it takes those people to get infected.

In the best-case scenario, 20% of the Worcester region’s population is infected, and it takes 18 months for that to happen. In the worse-case scenario, 60% of the population becomes infected in six months.

The Worcester area has 1,525 beds, but not many are typically available – just 425, according to the study. If 20% of the area population becomes infected, which is at the low end of commonly cited estimates, and the surge patients is spread over 18 months – flattening the curve, in the parlance of health officials – the region would need 589 beds.

ICU beds, which would be used for the sickest patients, would face a worse shortage.

Most who contract coronavirus aren’t expected to need intensive care, but only 43 such beds are typically available in Greater Worcester. If only 20% of area residents get the virus and the curve is flattened to 18 months, a projected 126 ICU beds will be needed, according to the Harvard researchers.

But the shortage could be drastically worse.

In the most severe prediction, of 60% of the area becoming infected in six months, the area would need 1,162 ICU beds. That’s 27 times greater than the number of beds typically available.

Early in the pandemic, it is difficult to predict the number of people who will actually catch the disease, as much will depend on how effective the social distancing measures will be. However, Marc Lipsitch, a professor of epidemiology at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, has estimated that 40% to 70% of the world’s population could become infected.

“Our goal is to give hospital leaders and policy makers a clear sense of when they will hit capacity, and strategic information on how to prepare for rising numbers of patients with COVID-19 needing care,” Dr. Ashish Jha, the director of the Harvard Global Health Institute, said in a statement.

Working to add space

Hospitals have already taken some action to add capacity by postponing most elective procedures for at least a few weeks, and MetroWest Medical Center has indefinitely called off a plan to eliminate acute care services at its Leonard Morse Hospital in Natick.

Milford Regional Medical Center is creating a temporary 3,800-square-foot facility at the back of the hospital to accommodate emergency department patients, and UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester has moved some intensive care beds to create a contiguous area for treating coronavirus patients.

Steward Health Care, the parent company for Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer, said it began stockpiling ventilators and personal protective equipment when the virus first emerged in the United States.

It is also planning to send coronavirus patients needing inpatient care at any of its area hospitals to one centralized facility, Carney Hospital in Boston. That will allow other Steward hospitals to continue caring for other patients while dedicating the right coronavirus resources in one place, the company said.

UMass Memorial Medical Center and Saint Vincent Hospital worked with Worcester city officials to plan for using the DCU Center for caring for coronavirus patients if or when the additional space is needed.

The Worcester hospital referral region has more than 652,000 adults, of which 81,000 – or 12% – are projected by the Harvard researchers to need hospitalization. More than 17,000 people, or nearly 3% of the population, could need an ICU bed.

Most of Central Massachusetts is in Worcester’s hospital referral region, but much of MetroWest is in Boston’s and part of the Blackstone Valley is in Providence’s. Those areas, too, are slated to see major shortages.

Boston, for example, is 20th worst among referral regions for total hospital beds, and 114th for ICU beds. Providence is 38th worst for total beds and 48th worst for ICU beds.

Equipment shortages already loom

Hospitals are already reporting shortages in some equipment, including in so-called N95 surgical masks at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester, with hospital leaders advising practitioners to reuse masks for multiple patients if necessary. That step isn’t normally done but has been deemed acceptable for a limited time by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

UMass Memorial has told providers to use albuterol inhalers only for patients who've tested positive for coronavirus or those under investigation with a high likelihood of a positive test. Other inhalers called nebulizers should be used for all other patients, such as those with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Marlborough Hospital has asked the Corridor 9/495 Regional Chamber of Commerce and the Marlborough Economic Development Corp. for help obtaining face masks, face shielding and ventilators, according to the chamber. Hospitals have also reported blood shortages.

The Massachusetts Nurses Association has lauded the delayed Leonard Morse Hospital closure and delaying unnecessary procedures but said there still appears to be a major shortage in capacity.

“The potential surge in volume of patients with possible exposure to or symptoms of COVID-19 illness still very much has the capacity to overwhelm our healthcare system,” the union said in a letter to Gov. Charlie Baker.

“The state should direct health care facilities to halt all planned bed, unit and facility closures. We should instead be looking at ways to increase capacity,” the group said.