Faced with declining patient discharge numbers and seeing a chance to pare costs that didn’t directly affect patients, UMass Memorial Health Care leaders in Worcester made a tough financial choice to cut much of its executive ranks.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Faced with declining patient discharge numbers and seeing a chance to pare costs that didn’t directly affect patients, UMass Memorial Health Care leaders in Worcester made a tough financial choice to cut much of its executive ranks.

Executive pay totaled more than $31 million the year Eric Dickson, the UMass Memorial president and CEO, took over in 2013. By 2017, that total executive pay fell below $15 million.

The executive headcount wasn’t cut quite in half, but UMass Memorial eliminated positions that became redundant with consolidation, such as when HealthAlliance and Clinton Hospital merged. Other reductions were made in IT and finance.

“We wanted a slimmer organization at the top,” said Sergio Melgar, chief financial officer for UMass Memorial. “It was very hard to promote anyone to a [vice president] in the organization during this timeframe. If we lost a VP, they were generally not replaced.”

UMass Memorial Health Care – Central Massachusetts’s largest employer – also reduced the number of employees by almost 8%, or nearly 1,200 workers, over a five-year period ending in 2017, the latest year with data available.

UMass is not alone in needing to make tough choices to keep as many patient services as it can.

With rising employee costs, regulatory requirements and insurance reimbursement, among other expenses, hospitals have not been immune from financial pressures despite being in such an in-demand industry.

“They view investments in their workforce, their communities, and the way in which they deliver care as among the most important investments they make,” said Catherine Bromberg, spokeswoman for the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association.

“However, hospitals are also forced to devote resources in areas that have no benefit to patients or the communities in which they reside,” Bromberg said. “For instance, administrative requirements from insurance companies and certain government regulations are both costly and labor-intensive. This red tape is too often a barrier for hospitals being able to invest in places that really matter.”

A mixed period in employment

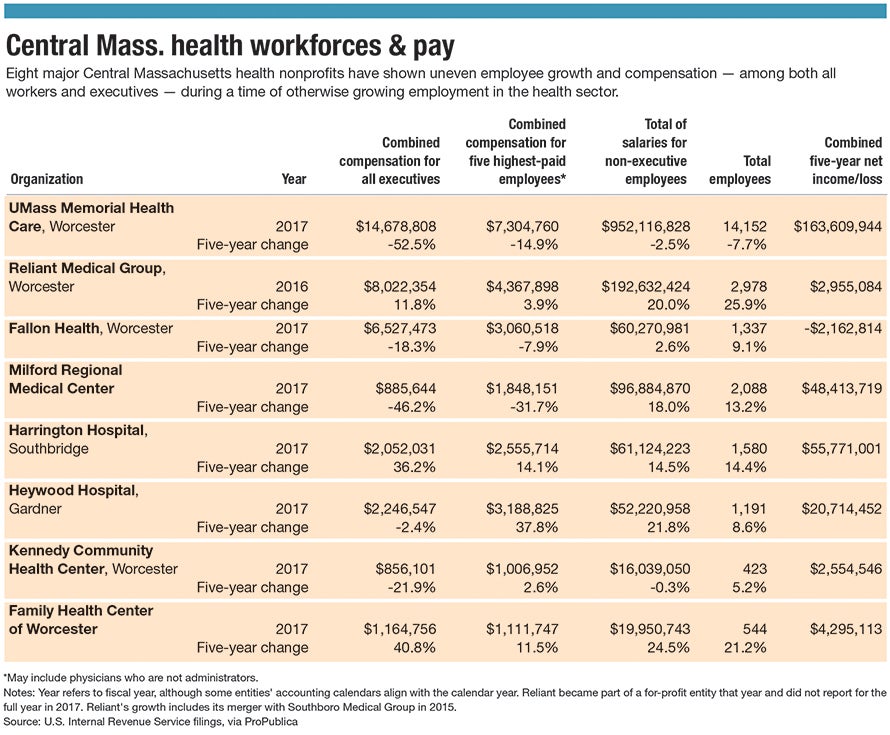

Over the last five years, other major healthcare employers in Central Massachusetts have adopted a similar cut-at-the-top model as UMass Memorial, although others typically are adding total staff while trimming those executive expenses, according to a Worcester Business Journal examination of filings with the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

At the Fallon Health, executive compensation dropped 18% while the Worcester insurers total workforce grew 9%.

Heywood Hospital in Gardner trimmed its total executive compensation 2% while adding 9% more staff in the last five years.

Milford Regional Medical Center has also sharply cut executive payroll, from more than $2 million to under $900,000 in one year. That comes as the hospital’s workforce rose 13%.

The Milford hospital had an 11% increase in patient discharges during that five-year period, according to the Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis.

In all, health care and social assistance jobs in Central Massachusetts grew 11% through 2017, keeping pace with growth across the state. But thanks to UMass’ cuts in recent years, total employment at eight major health nonprofits analyzed by the WBJ actually fell slightly, by 1%.

That loss was driven entirely by UMass Memorial. Other centers have beaten the region and state’s pace for an expanding healthcare industry.

The Family Health Center of Worcester, for example, has grown its workforce by more than one-fifth. Harrington Hospital in Southbridge has 14% more employees during that time.

Lou Brady, Family Health Center’s CEO, said the facility has simply grown to meet demand for patient care. The Family Health Center works often with patients who don’t speak English fluently or are homeless or battling addiction – areas requiring intensive services.

“We’ve needed to increase our providers and clinicians and support staff to keep pace with that need,” Brady said. “We actually need more [employees].”

For Harrington, the increase in employee count comes as the hospital expanded its emergency department in Webster and opened an urgent care center in Charlton. Harrington was awarded state grants for behavioral health initiatives allowing for a new patient navigator program and expanded outpatient services.

UMass Memorial’s 8% drop in employee count came during a roughly 5% drop in patient discharges at UMass’ Worcester campuses, a measure of less patient utilization during that time.

In the five years since Dickson took over as CEO at UMass Memorial, the healthcare system had a five-year net income of $164 million. But the system has reported fiscal constraints since then, including from lower Medicaid reimbursements and higher employee salary and retirement costs.

With those constraints in mind, UMass has acted accordingly.

In 2018, UMass eliminated a broad range of services: endoscopy services at Clinton Hospital, Plumley Village Health Services in Worcester, an inpatient pediatrics unit and a cardiac rehabilitation unit in Leominster and an urgent care center in Fitchburg.

In December, it announced it sold its stake in a pharmacy management unit for $263 million.

UMass Memorial is not expecting further cuts in this coming year, Melgar said, expecting a continued uptick in patient count. The system has nurse and doctor vacancies it is looking to fill.

Top executives still making millions

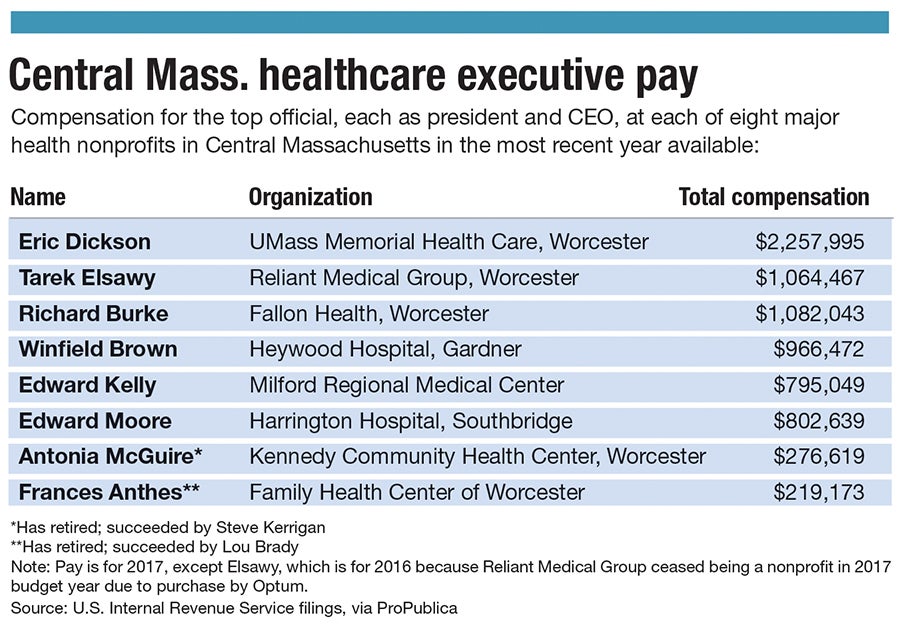

While the major Central Massachusetts healthcare organizations have trimmed executive pay, health organizations, wanting to draw and keep top talent, have continued to pay their top official well.

Dickson, of UMass Memorial, has gotten raises of more than $200,000 each year since he was promoted to the group’s top position in 2013. He made nearly $2.3 million in 2017. John O’Brien, his predecessor, took home $3.5 million in his final year.

Patrick Muldoon, then the president of UMass Memorial Medical Center, had a more than doubling of his compensation in a five-year period through 2017, when he took home $1.5 million. (His successor, Michael Gustafson, took over in 2018, a period for which data isn’t yet available.)

Compensation for Fallon Health’s president and CEO, Richard Burke, doubled to nearly $1.1 million in two years’ time from when he first took on the post on an interim basis. His predecessor, Patrick Hughes, twice made more than that amount in the final years of his tenure.