Mass. could run out of nursing home beds in four years

Photo I SHNS

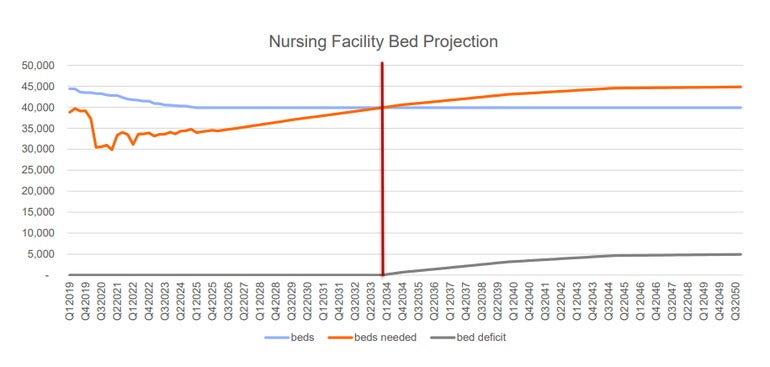

Nursing bed facility projections

Photo I SHNS

Nursing bed facility projections

Massachusetts nursing homes might run out of bed capacity years earlier than a task force recently forecast, according to a former budget chief of the secretariat focused on caring for older Bay Staters.

With the state's population of residents ages 80 and older expected to skyrocket over the next decade, nursing homes could hit their breaking point in 2029, said Pete Tiernan, past chief financial officer of the since-renamed Executive Office of Elder Affairs. His projection uses the same data as the task force -- but with a different way to zero in on the surge of Baby Boomers, including those who will soon age into nursing homes.

The Viability and Sustainability of Long-term Care Facilities Task Force pegged the tipping point at 2034, based on the volume of licensed beds and population forecasts from the UMass Donahue Institute. The "typical" age for nursing home residents is 80 years old, according to the report.

Tiernan, who says the task force's analysis underestimates the imminent strain on the state's nursing home sector, is urging the panel to retract and revise its report.

"I'm highly confident that they've made a flaw in their projecting methodology. My call to action is that they should basically rescind the report, engage with an actuary or statistician and revise their projections," Tiernan told the News Service, as he reflected on the estimates between 2025 and 2035. "My conclusion is that their approach, basically over that 10-year period, has the effect of underestimating demand by 50%."

Tiernan is principal at HCBS Solutions, a consulting firm focused on home- and community-based services for older adults. He's also a proponent of boosting the use of assisted living care settings.

Spokespeople for the Executive Office of Health and Human Services and the Executive Office of Aging & Independence -- which had designees on the task force -- did not answer News Service questions about Tiernan's critiques and whether a statistician or actuary was consulted for forecasting. Meeting materials are not available on the task force's public website.

Tiernan, who emailed his concerns to state officials who served on the task force, said he has not received responses.

Task force member Ron Pawelski said he tried to push the panel to seek funding from the Legislature, with the aim of supporting more detailed supply and demand analyses across the long-term care continuum, including skilled nursing facilities, assisted living residences and rest homes. That suggestion from Pawelski, who's president of Massachusetts Association of Residential Care Homes, appears near the end of the report under a section called "specific member statements."

While UMass Donahue Institute figures were "very valuable" in considering supply and demand, Pawelski said other data sources "could have been tapped, should have been tapped."

"There's a whole host of entities that are out there that specialize in doing supply and demand analysis," Pawelski said.

Tiernan said the report "does not serve the commonwealth well," as state officials brace for the impact of Baby Boomers flooding into nursing homes or requiring other types of care and services. The task force, created through a 2024 long-term care reform law, was charged with assessing demand for long-term care facilities over the next five and 10 years.

"Without judgment on the well-intentioned individuals who participated in the Task Force, this collective work product finding is highly defective," Tiernan wrote in his email to some task force members. "Given the expected reliance on the report for public policy development, the Task Force must recognize that it has been negligent in its duties. My impression of the report is such negligence is attributed to the Task Force not engaging with an actuary or qualified statistician to conduct the forecasting."

Nursing homes served about 55,000 residents in the first quarter of 2025, according to the report. By 2035, the task force predicted nursing homes would serve 67,000 residents within a quarter, which would represent a nearly 22% increase in utilization.

Tiernan said the task force appeared to make that estimate based on the state's population of all residents ages 70 and older growing by 25% over the next decade.

But Tiernan said the population growth forecast is starker when focusing only on residents ages 80 and older, a cohort that's expected to increase by 41% over the next 10 years. That age group is the "primary driver to nursing home utilization," he said.

While Massachusetts is currently home to 349,666 residents ages 80+, the report predicts the cohort will climb to 493,244 people in 2035.

"The Task Force's forecasting methodology is flawed because it assumes that individuals between 70 - 79 access nursing home services at the same rate of individuals 80+," Tiernan said. "I welcome a colleague or professional to explain how I may be mistaken, but there is no available logic that supports current nursing home capacity will be able to sustain a 41% surge to the core age cohort of Nursing Home Residents. Where the report is asserting a tipping point is reached in 2034, I suggest that if the authors were to better adjust for SNF Resident Age the same forecasting approach would estimate 2029 as the tipping point."

The report said factors that could cause the state to experience a nursing bed shortage earlier or later than 2034 include staffing challenges from immigration policy shifts, additional nursing home closures, investments in home- and community-based care, and evolving care models like offering skilled nursing at home.

Pawelski said the demand forecast should have also accounted for the backlog of patients waiting to be discharged from acute care hospitals and a settlement agreement last year that said the state would invest $1 billion to transition at least 2,400 nursing home residents to the community over the next eight years.

The task force used a model that assumed no change to the current number of licensed beds, which sits at 39,899. But more nursing homes are likely to shutter in the coming years, which would result in a loss of beds, said Tara Gregorio, a task force member and president of the Massachusetts Senior Care Association.

Nursing homes are also working on implementing dedensification regulations, in which facilities are shifting away from larger rooms -- which could accommodate three beds -- to smaller formats with two beds. Gregorio said that would cost the state between 1,500 to 2,000 beds, while providers must also keep up with growing demand for dementia care.

By February, nursing homes could also lose at least 2,000 direct care staff with the Trump administration terminating Temporary Protected Status for Haitian immigrants, she said.

Those factors signal Massachusetts nursing homes will "reach a crossover sooner than 2034," Gregorio said.

"It's not a matter of if we are going to have a crossover between between demand and supply -- it's a matter of when," she said. "And that's a real new, I think, significant action point for the commonwealth that we will run out of nursing facility beds. And we need to act today, and we need to act immediately."

Pawelski said the task force ran into time constraints that hindered in-depth analysis. The panel's report was due at the end of July.

"We didn't have the level of detail where we really got into understanding all of the intricacies associated with what was being presented (and) time to determine, I'm going to say, to validate what the numbers are," Pawelski said.

0 Comments