In 1936, seven white men judged which neighborhoods of Worcester were not viable for real estate financing. Today, as rising costs overburden half of renters in the city, those impacted the most are from those neighborhoods still suffering from lack of investment.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Worcester is built on its hills. There’s Grafton Hill, Vernon Hill, Hancock Hill, Green Hill Park, Bell Hill, Chandler Hill. The hills define the city. The College of the Holy Cross is on a hill. Same for Worcester Academy and Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Even Assumption University is near the top of an incline.

When Adam Davidson wrote about Worcester for The New York Times Magazine in 2016 he called it the “the middle” and an “engine for betterment until the middle of the 20th century, a magical place that transformed lost and impoverished lives.” It’s a city he also said “wasn’t anybody’s first choice, at least not in my family.”

For Davidson, Worcester stood for something it was in the early 20th century: A city built on workers making a life for themselves. A Gateway City with the right mix of factory jobs, land, possibility, the potential for higher education, and affordable housing. Figuratively, people climbed the social ladder.

While most of this is true, Worcester, like many other American cities, has its own uneven history as a gateway to a better life.

It’s not always been for everyone.

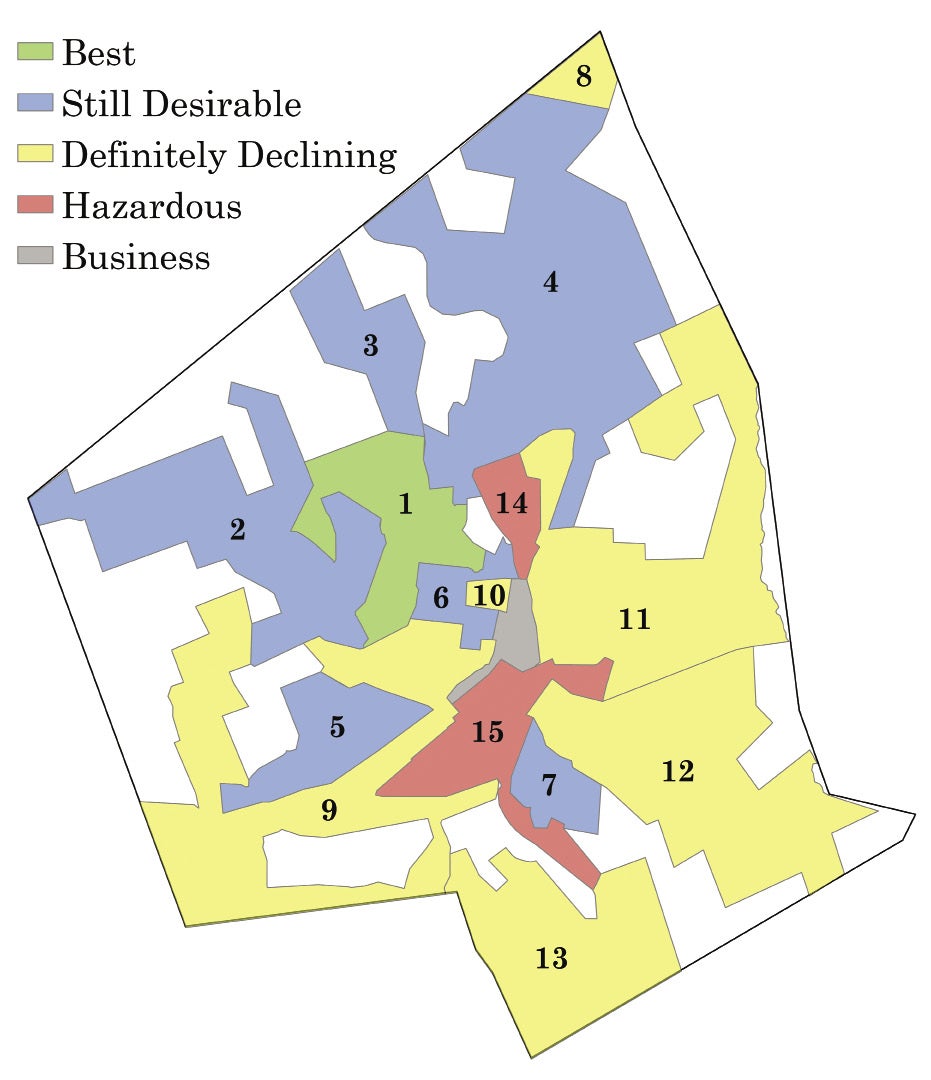

Worcester has gone through many iterations – including plenty of tough times – but its growth, in a lot of ways, has been predictable. It’s a city shaped not only by its hills, but also by a map. Specifically, a realty area map drawn and looked over by seven white men in 1936 with ties to the federal government, and the city’s banking and real estate industries. The map was commissioned by the Home Owners' Loan Corp. and used problematic – and, in some cases, downright racist – criteria to classify the city into five areas: Best, Still Desirable, Definitely Declining, Hazardous, and Business.

And today, the city, like so many others where these maps drawn, is still dealing with this legacy.

As part of its joint effort with the Worcester Business Journal on this “Redlining: An Economic Legacy” project, the Worcester Regional Research Bureau obtained a copy of the 1936 redlining map of Worcester from Robert Nelson at the University of Richmond. Nelson started the Mapping Inequality project, where he has collected redlining maps for more than 200 cities in America and posted them online with an interactive tool.

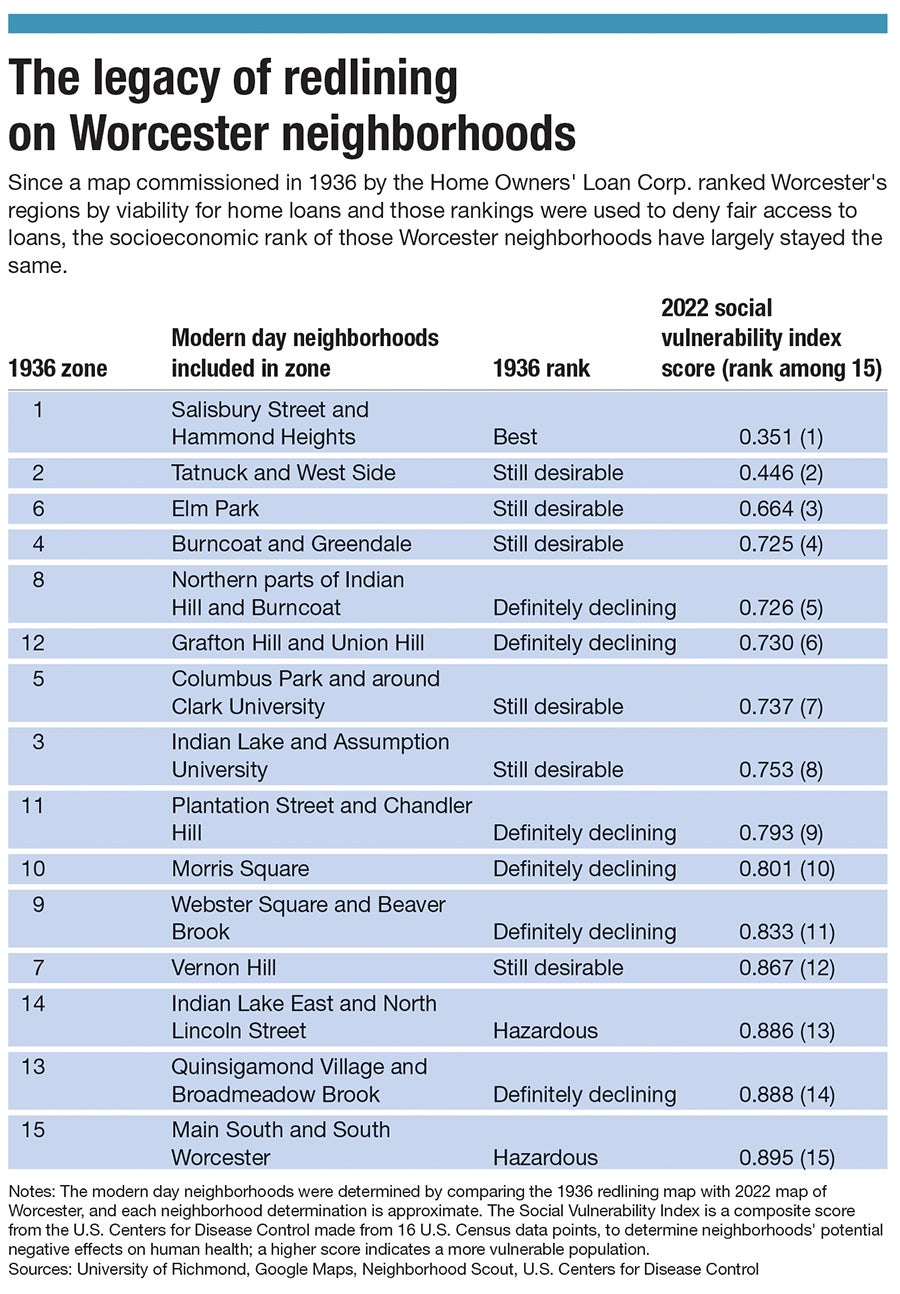

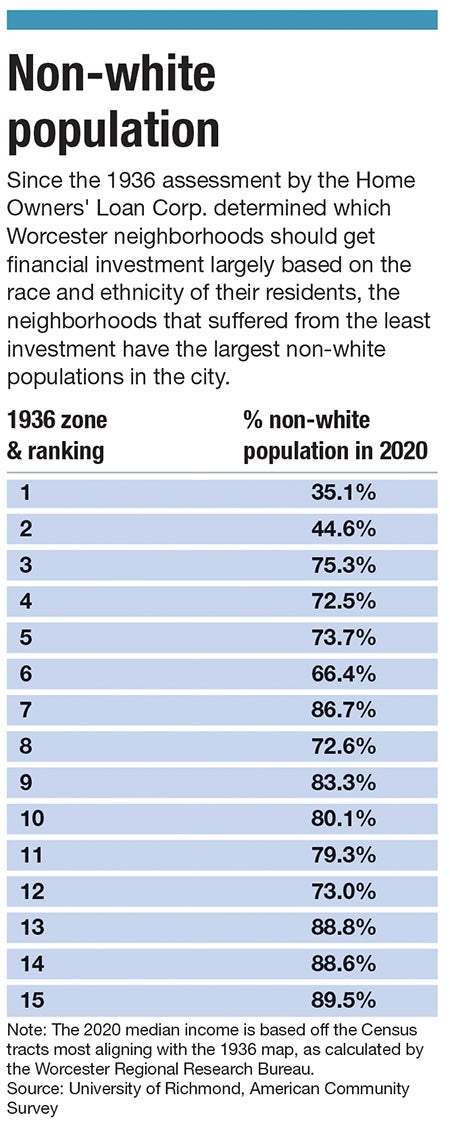

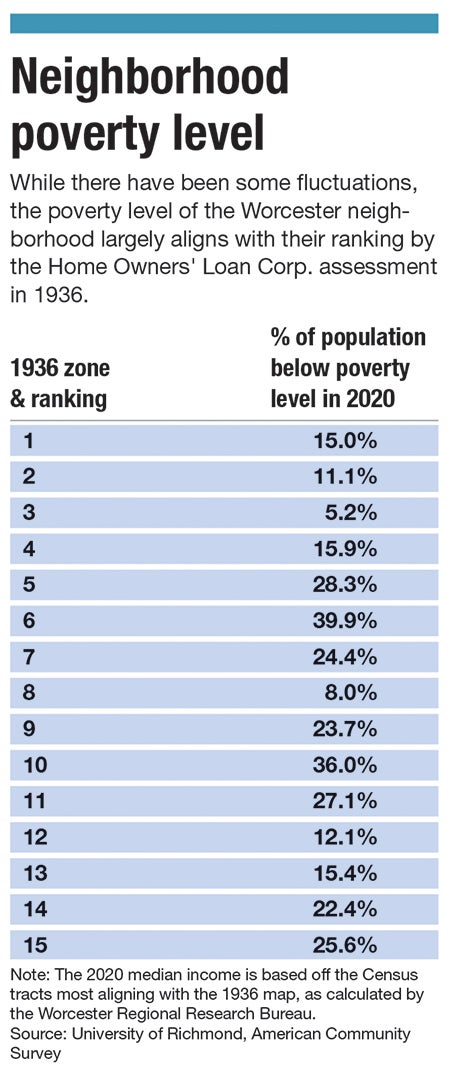

WRRB compared the redlined map to modern Worcester neighborhoods, using 2010-2022 demographic, economic, and health data to see how the decisions made back in 1936 reverberated throughout the city. Outside of a few neighborhoods, WRRB found the way the map was drawn is largely how the city is shaped today in terms of wealth. The map not only set the standards for its day, but it locked neighborhoods into economic cycles, where those scored the worst 86 years ago are still at the bottom.

The Main South area was considered the worst neighborhood in the city in 1936, as HOLC said its residents were comprised of French, Polish, and Lithuanians, saying on the redlining map “The majority are industrial workers and laborers of the poorer class.”

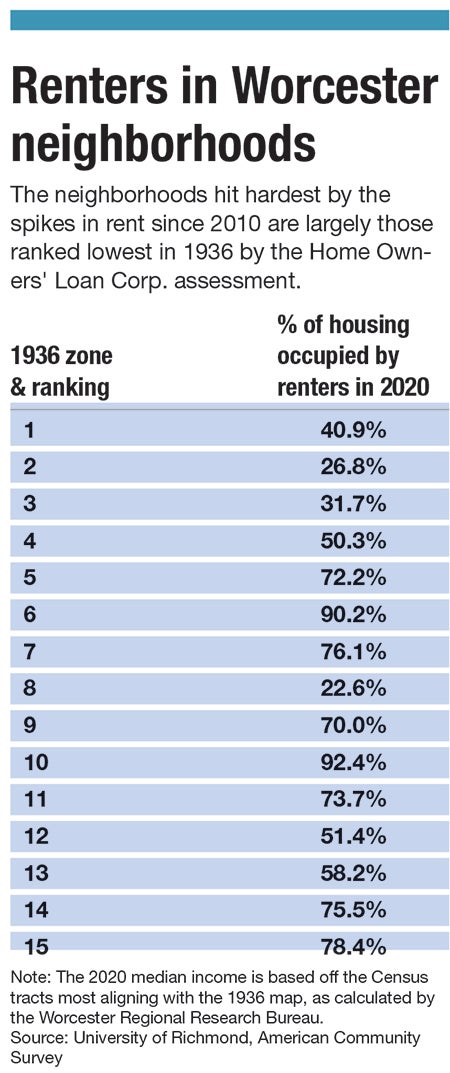

Since the HOLC’s Hazardous label in 1936 signaled to banks the Main South neighborhood was a risky investment, residents who lived there largely couldn’t get loans to buy or renovate homes. The main people who could afford to own homes were the wealthy who lived outside the neighborhood and rented to the people who lived in Main South. The neighborhood remains overwhelmingly renter-occupied today, and as rental prices have spiked throughout the city since 2010, the people bearing the brunt of being cost-burdened by these rising prices are those living in the neighborhoods redlined in 1936.

Using the 2020 Social Vulnerability Index compiled by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control to determine how neighborhood conditions impact people’s health, the WRRB found residents of Main South now are the most vulnerable in Worcester.

In fact, when looking at that Social Vulnerability Index data, the two neighborhoods ranked the best in 1936 stayed at the top while the bottom three remained there. What also becomes apparent when looking at the map is that the impact of redlined neighborhoods stretch beyond their border and that even being near a redlined neighborhood meant a section would eventually falter.

The redlined map of Worcester follows the guidelines set up by HOLC and delineates neighborhoods in a straightforward and unempathetic way. It ranks the sections in 15 categories drawn in some funky shapes to outline where certain demographics and races live, as well as where factories are.

The top area is near Hancock Hill and the section surrounding most of Salisbury Street, which has some of the city’s biggest and oldest homes and “are occupied by professional men and business executives,” according to the HOLC assessment. The second best section, according to the map, is the Tatnuck and West side area of the city, which has no apparent “detrimental influence” and “some of the better class Jewish people” concentrated in the area. Near Elm Park is the sixth best neighborhood and has people collecting rent in two family homes for “$65 to $80 a floor.”

As you get further down the list of redlined neighborhoods, the areas are more defined by the people who live in them. The ninth best area in the city is near Beaver Brook where, “there is a small concentration of negroes southeast of Beaver Brook playground, although it is not spreading to adjacent streets.” The 12th ranked neighborhood, near today’s Grafton Hill and Union Hill, is “principally inhabited by Jewish people of the poorer class.”

This is standard language of the time for HOLC maps.

It not only deals with wealth, home types (multi-family homes are less desirable for a neighborhood than single-family), and geography, but also race and ethnicity.

“It is straight out of [HOLC’s] playbooks, and I think if you read similar maps from other cities the language actually – I've read it for some other cities – resonates,” said Deborah Martin, professor at Clark University's Graduate School of Geography. “It's typical. Taking different demographic groups and ascribing home value or certain characteristics to them and talking about it in a dispassionate way. It's classic that the Jewish neighborhoods and any neighborhood with any Black people in them are definitely declining – they are declining by definition to the HOLC because of those categories.”

Those categories and the way the HOLC maps were designed out of a legacy of racist policy set forth after the Civil War to slow integration and keep wealth and property out of Black people and other minority groups’ hands.

Home ownership has been viewed as a way for middle-class families to accrue wealth since the early 1900s. Davidson’s family bought a home and started to build a new life in the middle, out of poverty.

“For my father’s family,” Davidson writes, “the dreams fulfilled by this house had meant a climb from bare subsistence to the middle.”

But for the people in those neighborhoods redlined in 1936, the dream of homeownership is an impossible promise, and when Worcester goes through an economic wave causing rental prices to spike – like they have from 2010 to 2022 – those residents are the ones who suffer the most.

In the early 20th century, President Woodrow Wilson’s administration made it a point of emphasis to make homebuying easier because the government feared the Marxist Russian revolution that took hold would jump to the United States and threaten the country’s capitalist system, according to Richard Rothstein, author of “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America” and a distinguished fellow of the Economic Policy Institute and a senior fellow emeritus at the Thurgood Marshall Institute of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

To stop that, the government believed getting white Americans to become homeowners would keep them invested in the capitalist system, according to Rothstein.

At the same time, zoning policies had been put into place by various cities and towns since the end of the Civil War. Local officials segregated cities and pushed Black people out of small towns and into more and more crowded areas of cities.

Even with the push by the government to get white families into home ownership, it was still too expensive. Banks usually required 50% down payments for a loan and for the loans to be paid off in five to seven years. When the Great Depression hit, that kind of financial commitment became impossible.

So, in 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt and his administration created HOLC, which was charged with buying existing mortgages close to foreclosure and giving those owners new loans up to 15 years. The new loans made it so owners paid little interest, and the borrower owned the home at the end, giving the borrowers equity in their homes as they paid off the mortgage. That wasn’t the case before as loans were mostly based on interest payments. This meant if they sold their homes even while still paying off the loan, they took some money with them for their next move.

With the new loan program, though, it meant that HOLC needed to delineate between borrowers who could pay off the loan with regular payments and others it feared would default. To do this, it hired local real estate agents to create maps and appraise homes and homeowners. This resulted in HOLC drawing color-coded maps showing the neighborhoods safest for loans as green and the riskiest as red, thus the term “redlining.” The zones were created on racial lines, following the 1922 ethics rule implemented by the National Association of Realtors to not allow agents to sell homes to Black people in white neighborhoods.

A year after HOLC was created, Roosevelt created the Federal Housing Administration to help people buy homes by insuring bank mortgages up to 80% of purchase prices with 20-year terms. The FHA did its own appraisals of property to make sure the loans weren’t risky and it even included a “whites-only” requirement for the because the FHA believed integrated neighborhoods, or even white neighborhoods near Black ones, were too risky.

This set a precedent and created a cycle of generational wealth that we are still dealing with today. Black people and other minority groups, including Jewish people, were excluded from getting reasonable loans to buy homes, which would have allowed them to accrue wealth through increased equity. This also meant homeowners in neighborhoods near a red neighborhood on the map were encouraged to sell their home, as those properties had already begun to lose value since banks were less likely to give out loans for those homes.

“It was real estate agents who did that originally, flipping the houses, telling homeowners, ‘Blacks are moving in and you should sell at a premium to me,’” said Daina Harvey, professor of sociology and anthropology at the College of Holy Cross. “And then I am going to mark it up 200-300% for a Black family and then in 10 years it is not going to be worth any money.”

FHA loans allowed white buyers the chance to begin to buy property and in turn create a cycle of wealth. For minorities, and especially the Black middle class, that opportunity was ruined. They could not secure loans and in a lot of cases couldn’t buy homes because, according to Rothstein, property owners and builders put language in home deeds and pacts among neighbors prohibiting future resales of homes to Black people.

Add all of this alongside the maps and the FHA discouraging banks from giving out loans to neighborhoods in cities and favored loans for freshly built suburbs, and you have white people fleeing the cities. This made the neighborhoods they left even less valuable and the ones they moved to more valuable, creating a roadmap where a Black person buys into an area and finds the purchase they made is underwater.

“You bought an $80,000 house for $120,000, and now it’s worth $40,000; and so you’re hemorrhaging money,” Harvey said. “This happens at the same time as we see deindustrialization and things like that take place, so your parents had really good jobs at Ford or GM or something like that, and now they don't have any jobs. They can't send you to college because they can't borrow any money based on the value of their home, which is underwater now.”

With that, the next generational barrier grows. There’s now not only a equity wealth gap, but families in deep debt with no ability to send their children to college to create some educational value, as the financial system won’t allow them to finance higher education, which becomes another version generational wealth because it allows people to leverage their way out of poverty for higher-paying jobs that value the degree they receive from a higher institution of learning.

“Today's residential segregation in the North, South, Midwest, and West is not the unintended consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law or regulation but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States. The policy was so systematic and forceful that its effects endure today,” Rothstein writes.

Those effects for Worcester in 2020 include 75% of its homes being owned by white people in a city whose population is 67% white, while about half of all renters are people of color, according to the WRRB report “Static Income, Rising Costs: Renting in the Heart of the Commonwealth” released on Dec. 12.

As housing costs have spiked in Worcester over the past decade, the renters are the ones who are impacted the most.

The map of Worcester foretells the way the city will grow as it moves through the 20th and into the 21st centuries. Patterns arise, and there’s even a larger knock-on effect by the way the areas are drawn because each redlined neighborhood has an outsized impact on the ones around them.

For example, the seventh district, which is modern day Vernon Hill, went from the seventh best district in the city in 1936 and dropped to the 12th in 2020 because of how the map and the neighborhoods around it impacted the homes there. The district is almost surrounded by the 15th district, one of the two red neighborhoods delineated on the original map. Vernon Hill is an old neighborhood of triple deckers, and because of its proximity it becomes an area where it’s harder to get a loan.

This decrease in property value also makes it a place where the government might want to build a highway, like I-290.

“Planners for the Interstate Highway System designated Black and brown areas as undesirable and either destroyed them to make way for highways or located highways in ways that separated the neighborhoods from job-rich areas,” Heather McGhee writes in "The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together."

Families were already leaving Vernon Hill before I-290 was constructed, but once it weaved its way along the border with the redlined District 15, the neighborhood's future reverses.

“Part of what happened to [Vernon Hill] is that Water Street was decimated when 290 went through and separated the owners from their property,” Martin said. “But also, those owners were relocating to the West Side. You have that happening not at the same time but they feed into each other.”

Homes near highways or under highways or along highways are traditionally less valuable because of noise, pollution, and traffic. They’re the opposite of the American dream home society was sold.

Around the same time I-290 was being built, a lot of the homeowners in Vernon Hill moved to the West Side. They owned property and businesses in the Water Street neighborhood and were already beginning to move out.

“The Jews on Vernon Hill owned the businesses on Water Street – the [home] owners worked in the businesses on Water Street,” Martin said. “But it was a more middle and upper class, and in fact they are some of the same people who, in the 30 years after this map was drawn, relocated maybe even only 20 to 30 years, relocated to primarily zone 2.”

Zone 2 was the second best area in the city to live and there Jews were regarded for their “pride in homeownership,” according to the 1936 redlined map. Martin points out they had more income and thus considered a better-class Jewish person.

With I-290 on an overlay of the old redlining map of Worcestrer, the highway runs through four of the five 1936 zones listed at the bottom of the 2020 Social Vulnerability Index, and its impact can be attributed to part of Vernon Hill’s decline against its perception in 1936, which was high because it was the top of the hill and included “rich people,” according to the HOLC assessment.

“Highways are built where red and yellow lines were,” Martin said. “Because that was where poor people were that you could displace and were disproportionately renters, and that was a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

What happens in an area like Vernon Hill is that investment disappears. Without investment, it struggles to keep up and the cycle of devaluation continues until homeowners are all either pushed out, leave or pass away and their family sells the property to speculative buyers more interested in creating wealth, not through property value but by collecting rent.

Since these cycles have compounded problems in Worcester’s neighborhoods over the past 86 years, the redlining map largely hasn’t changed.

“Being graded with a ‘C’ or a ‘D’ in 1936 is today associated with higher poverty rates, a higher non-white population, a lower median income, and a higher percentage of renter-occupied units even after more than 80 years,” WRRB writes in its report “Static Income, Rising Costs: Renting in the Heart of the Commonwealth” released on Dec. 12.

Using Census tract data from 2020, the neighborhoods with the greatest portion of renter-occupied units in the city lines up with the old redlining map, showing the same areas impacted by redlining are now more than 80% rental units.

Now in 2020, more than 75% of Worcester homes are owned by white people while 7.5% are owned by Black people, 10% by Latino, and 6% Asian.

At the same time, the number of white renters in Worcester is 51.1% compared to 47.5% of renters who are Latino, Black, and Asian.

Since housing costs have spiked in Worcester between 2010 and 2022, homeowners are less likely to be cost-burdened today than renters, with 28% of homeowners spending more than 30% of their income on housing vs. 51% of renters

This cycle won’t ease as rent in the city continues to rise, WRRB writes. The average cost of rent increased 80% from March 2015 to August 2022, from roughly $1,000 to a little more than $1,800 per month.

Part of the reason for the spike in rents over the past seven years has been the slow increase of new homes coming online in Worcester, as the city added 1,848 new housing units from 2010 to 2020, an increase of 2.6% (compared to 3% both in Worcester County and Massachusetts and 7% nationally).

There’s constant talk at the city level for the need for housing in the city, which is nothing new. There has been a housing shortage in America dating back to the beginning of the 20th century and then especially after veterans returned from the two World Wars. And it’s fallen on the city to figure out how to ease that shortage by determining where housing would be built and what kind of housing it would be.

“It is about City Hall making an emphasis on who is the kind of developer we want to come into the city,” said Ramon Borges-Mendez, associate professor of community development and planning at Clark University in Worcester. “Would you like developers coming into the city that don't really think about what they are trying to do and are committed to the difficulties of understanding how you put together affordable housing? Or do you want to bring people who are free marketers who are just in the market of making a big buck? There is a difference.”

One of the people in charge of much of the early 20th century housing in the city was Raymond Harold, chairman and CEO of First Federal Savings and Loan Association, treasurer for the Worcester Home & Equity Cooperative Bank, chairman of the Worcester Housing Authority, and later chairman of the Worcester Redevelopment Authority. Harold has been called the driving force behind the city’s plans for urban renewal, and he helped build housing for returning veterans after WWII as well as Curtis Apartments, Great Brook Valley Gardens and Booth Apartments.

Harold also assisted and advised on the redlined Worcester HOLC realty map, which was completed on Feb. 10, 1936, with five other local advisors and one field agent. While Harold did build some low-income housing and housed veterans returning home from the war, he set the city in a way that has forced large neighborhoods and its population unable to gain a foothold on the promise of the American dream.

And the city and its residents have not been able to break the cycle.

Efforts to fix the impacts of the redlining have included creating community groups like Main South Community Development Corp. and Worcester Common Ground, Inc., which was set up in 1988 to help people find affordable housing. Now, Worcester Common Ground, which is a land trust, buys property in its neighborhood, fixes it up and either rents it or sells it to a first-time home buyer who may not be able to afford a home in the city. The deed attached to the home says it must stay affordable in perpetuity.

This not only gives people a chance to buy a home and gain wealth via equity, which they may not have been able to achieve before, but gives the city some more affordable housing in a neighborhood of three-deckers once a place for immigrants to buy a home and bring their family and friends over to work and live.

But those efforts have been limited, as the 13.5% of Worcester housing stock deemed affordable is lower than Boston’s 20% and Springfield’s 16%, according to a WGBH story in June.

Borges-Mendez has studied redlining impact across other cities and become keenly aware of Worcester’s current housing issues as a member of Worcester Common Ground. He had a student, Nick Meliss, unearth a copy of Worcester’s redlining map from 1936, which has been part of their own research.

Borges-Mendez wants the city government in Worcester to think about who has decided to partner with for new housing development. The city needs to rethink its strategy and push back on developers who want to come into the city, make money, and move on. He sees every new development, every new home, as a chance for the city to welcome in immigrants and blue-collar workers.

“There are developers out there who want and who would like and who would think that creating affordable and cost-effective housing is important,” Borges-Mendez said. “And there are others who don't give a shit and don't care.

“So it will depend on who you want to bring into the city, and if you are really hard ass, you can create mechanisms where you bring developers who are worthy, not developers who simply want to make a buck. That is an important part of the story,” he said.

While the cycle of redlining is racist in its programming, it’s also one that profiteers off of the poorer classes. It allows the upper-class to take something and value it to a point so their investment flourishes while at the same time destroying other people’s, which then the cycle feeds off of again because people with money have the means to invest in distressed assets, which is what has happened in the city as it is now faced with a shortage of affordable housing and more land and homes are being snapped up for big developers building more luxury and market-rate apartments like the ones at the Voke Loft and 145 Front Street at City Square.

While we look toward the future, it’s instructive to look at a map like the one from 1936. It lays out all of the biases and tells us the story of why Worcester looks like it does today.

“One of the things that screams out of this map is the west-side/east-side/south-side thing holds tremendously true,” Martin said. “The areas today that people talk about as upper-income Worcester – the West Side – are all by far where the majority of blue and the one green area is [on the redlined map].

“These patterns were set very early, and you can see the way people talk about class and the way they talk about race in the city,” she said.

If you’re cost-burdened, there’s no way to build wealth. You’re struggling each month to pay to live. Saving and creating wealth becomes more difficult and at any moment bad luck strikes and sends you tumbling down again, unable to even pay for a place to live because it costs too much.

And it’s the same groups and areas of the city reliving this fate all over again. It’s the same story. It's the same hill needing to be climbed. Like before, it’s dangerous and still littered with traps and potholes.