Chizoma Nosike wouldn’t have known it a year ago, but a federal business loan may be the reason her company, Acclaim Home Health Care in Worcester, is still in operation.

Get Instant Access to This Article

Subscribe to Worcester Business Journal and get immediate access to all of our subscriber-only content and much more.

- Critical Central Massachusetts business news updated daily.

- Immediate access to all subscriber-only content on our website.

- Bi-weekly print or digital editions of our award-winning publication.

- Special bonus issues like the WBJ Book of Lists.

- Exclusive ticket prize draws for our in-person events.

Click here to purchase a paywall bypass link for this article.

Chizoma Nosike wouldn’t have known it a year ago, but a federal business loan may be the reason her company, Acclaim Home Health Care in Worcester, is still in operation.

Last year, Nosike, a physiotherapist from Nigeria, switched from a major national bank to the locally owned Webster Five, wanting a more personal relationship with her banker. As a Black business owner, she knows firsthand the challenges involved with getting financing: She had to sell a Worcester triple-decker just to get her business off the ground 14 years ago.

Back then, Nosike couldn’t get a business loan.

“Not a penny,” Nosike said.

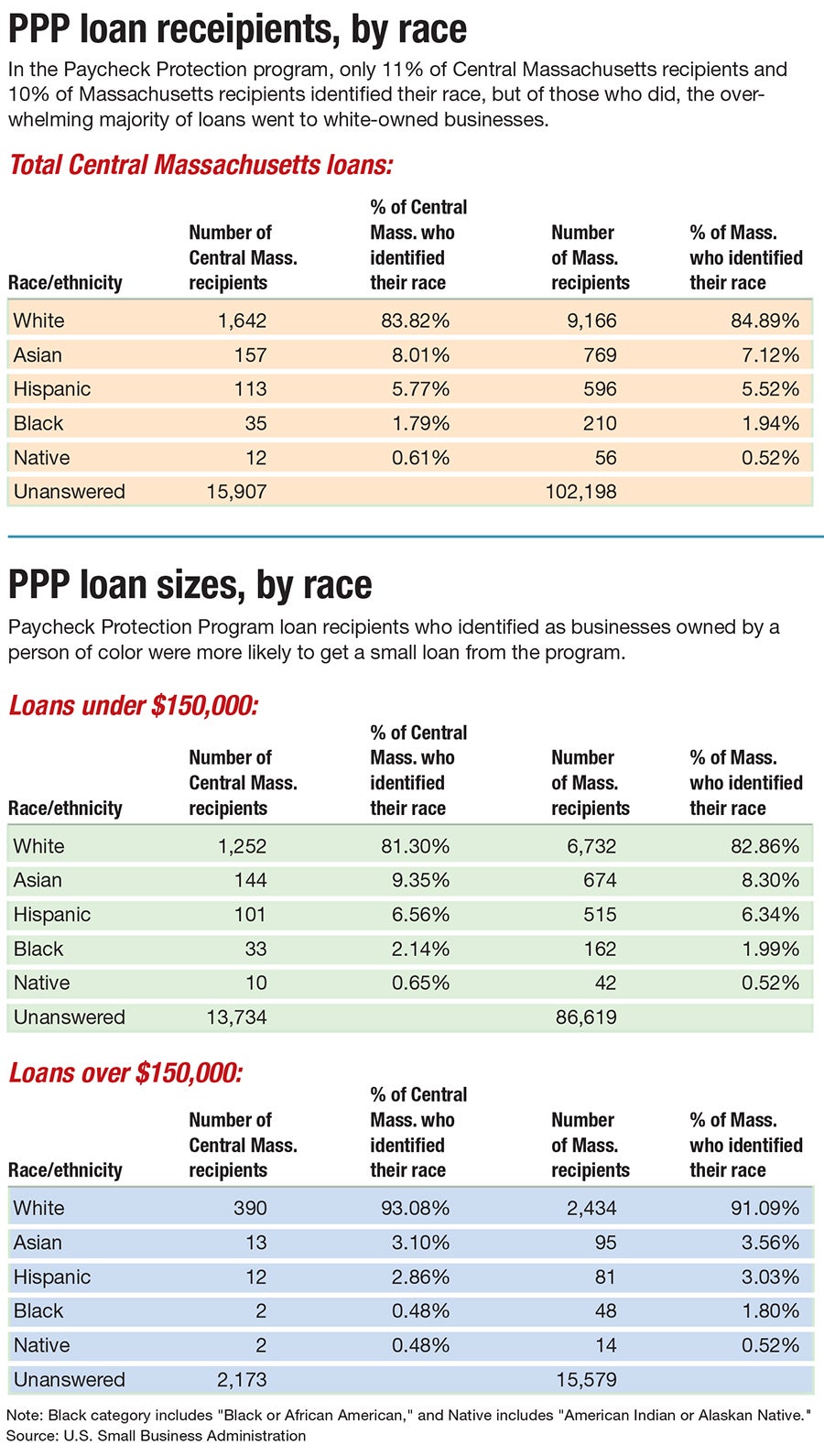

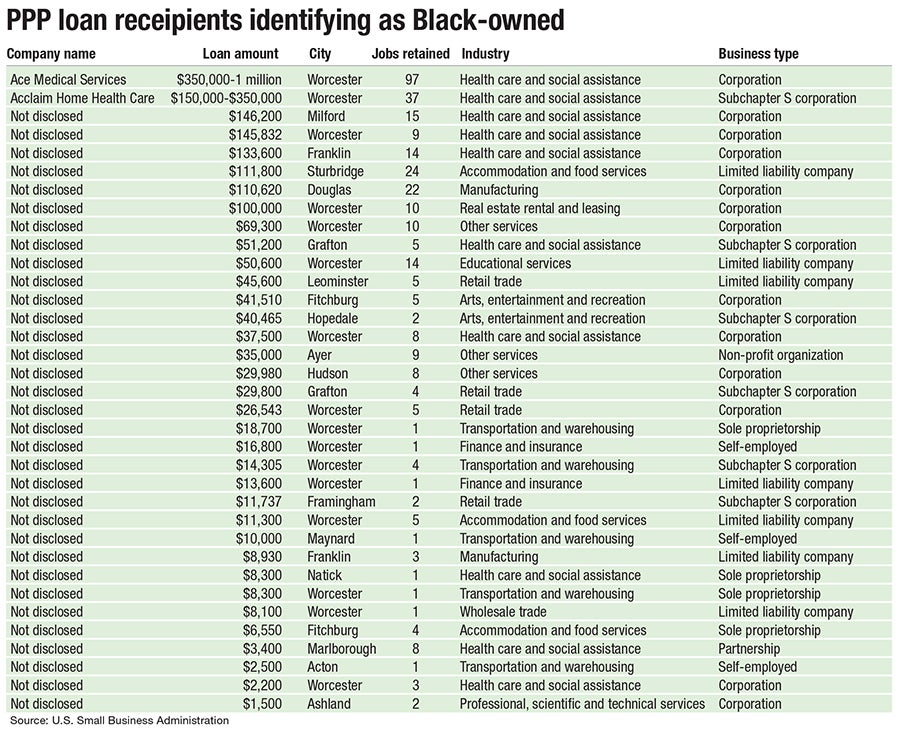

Now Nosike is one of just two identified Black-owned businesses in Central Massachusetts among the nearly 18,000 local businesses who received loans from the $669-billion federal Paycheck Protection Program to help stay afloat through the coronavirus pandemic, according to a Worcester Business Journal review of U.S. Small Business Administration data.

For Acclaim Home Health Care, its six-figure loan helped a few dozen physical, occupational and speech therapists stay on the job at a time when many people might be reluctant to have visiting nurses in their homes.

“If I didn't have the relationship I have with the bank I have now, I probably wouldn't have gotten it,” Noskie said of her PPP loan. “That's why I changed banks. You find a lot of banks that say they support local businesses but when push comes to shove, they don't really.”

Few recorded loans to minority businesses

When U.S. Congress created the PPP as part of the $2-trillion CARES Act as a lifeline for businesses, it directed the SBA to ensure underserved and rural businesses, including minority-owned companies, received priority in the program. Yet, in the SBA inspector general’s review of the program in May, its report found that didn’t happen.

Those national findings rung true in Central Massachusetts, too.

In roughly nine out of 10 cases, the race or ethnicity of a recipient’s owner in Central Massachusetts was left unanswered. Details were also often left blank for gender or veteran status.

About three-fourths of all PPP loans didn’t provide any demographic information because the information was not provided by borrowers, said Elizabeth Moisuk, the SBA’s regional communications director for its New England office.

The SBA is working to collect more demographic information from borrowers to better understand which small businesses are benefiting from PPP loans, she said.

Because demographic information was voluntary, only 35 Black-owned businesses in Central Massachusetts are reported as receiving PPP aid related to the pandemic.

Of those 35, they were more likely to receive smaller loans than the average for Central Massachusetts companies. While 17.7% of area recipients received over $150,000, the rate was 5.7% for Black recipients. Black-owned businesses, at least in Worcester County, tend to be smaller than businesses over all, according to U.S. Census Bureau data, but not by that large of a gap.

Mike Elmes, a business professor at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, called the Central Massachusetts data consistent with what he’s seen elsewhere.

“It’s clear the minority-owned businesses have had very poor success getting PPP and small business loans,” Elmes said. “This, despite that they are frequently asking for much less money than many non-minority owned businesses, strikes me as evidence for systemic racism in how these programs are being administered. The impacts on minority businesses are and will be devastating.”

Minority businesses outnumbered

Very few businesses have Black owners to begin with, locally and nationally.

In Worcester County, 0.8% of businesses have a Black owner, despite Black residents making up 6% of the population, according to the U.S. Census. Across Massachusetts, 1.4% of businesses are Black-owned, compared to 8.9% of the population. Nationally, those numbers are 2.2% and 13.4%, respectively.

Of those Central Massachusetts businesses who specified the race or ethnicity of their owner in the PPP applications, 1,642 said they were white-owned. Another 157 were Asian-owned, 113 were Hispanic, and 12 were Native.

That divide among races in loan recipients wasn't unique to Central Mass.

Nationally, among those who received $150,000 or more, recipients were 45 times more likely to identify as white-owned than Black-owned.

National studies have supported the argument Black businesses didn’t get a fair shake at PPP funds.

“By distributing PPP funds through eligible SBA-approved lenders, banks and credit unions, the program ensures that businesses of color that have historically lacked access to credit are likely to face barriers in accessing critical PPP loans,” the Center for Responsible Lending, a North Carolina-based advocacy group, said at the outset of the program.

In the past five years, white-owned businesses were twice as likely to access credit from a bank, the center said. The PPP’s fee structure heavily discouraged lending to smaller businesses or the self-employed, which are more likely to be minority-owned, it said.

Another group, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, conducted a study to see how business owners of different colors would fare. The nonprofit had testers with names and voices it found to be easily identifiable with a race contact 32 bank branches in its home city of Washington, D.C. Their financial profiles, including credit histories strong enough to qualify for a loan, otherwise matched.

Black testers were treated differently, the coalition said.

In 43% of the cases, the white would-be applicants were treated more favorably, including being encouraged to apply for a loan. In some cases, Black testers were discouraged from applying for a loan, or asked more questions about their business.

Other findings include a national survey in mid-May from the equal rights groups Color of Change and Unidos finding 8% of Black business owners reported receiving the financial assistance they requested from the PPP program. Another 23% said they received no assistance.

Rashad Robinson, the president of Color of Change, told The New York Times the lack of financial assistance could mean the end of many of the businesses.

“If we don’t get policies to protect these communities,” Robinson said, “we will lose a generation of Black and brown businesses, which will have deep impacts on our entire country’s economy.”

Compounding the issue is Black- and other minority-owned businesses have been found to be disproportionately hurt by the pandemic to begin with.

A working paper by Robert Fairlie, an economics professor at the University of California Santa Cruz, found Black-owned businesses to have failed in the first months of the pandemic at nearly double the rate of those overall: 41% compared to 22%. Hispanic-owned businesses failed over that period – from February to April – at a rate of 32%, Cruz found.