Many generations, one workforce: Communications issues, clashes over values, and how to navigate the most age-diverse workforce ever

Image | Adobe Stock

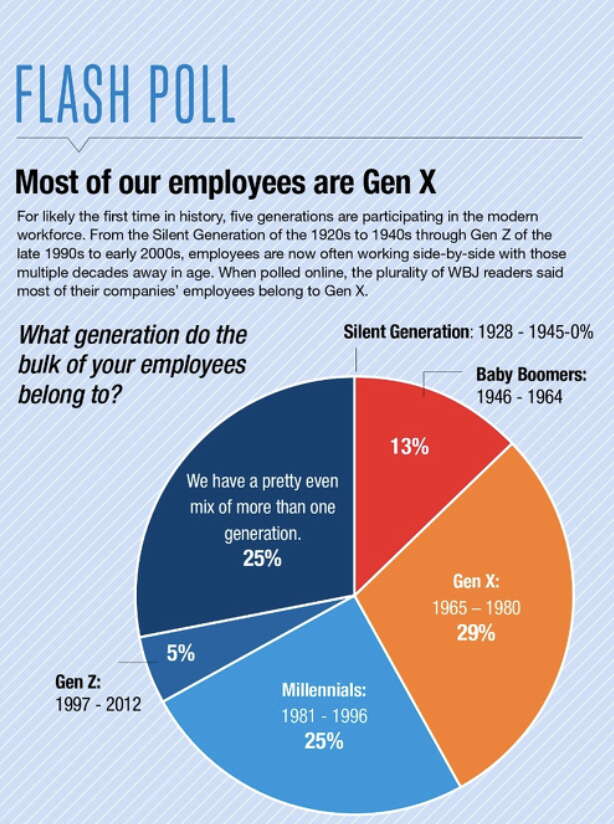

For the first time in history, five generations are participating in the workforce: the Silent Generation, Baby Boomers, Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z.

Image | Adobe Stock

For the first time in history, five generations are participating in the workforce: the Silent Generation, Baby Boomers, Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z.

For the first time in history, five generations are participating in America’s workforce. This means both those who were raised on “I Love Lucy” and those who spent their childhoods watching “Wizards of Waverly Place” might be sitting cubicle to cubicle.

This unprecedented intergenerational workforce comes with a wealth of different workforce norms and expectations that arguably make it the most ideologically and culturally heterogenous workforce to date.

These different convictions bring their workplaces a plethora of benefits and conflicts. For Central Massachusetts leaders, as complicated as this time may be, it opens the door to merge different expertise and experiences, making a workforce fit for the everchanging landscape of workplace modernity.

How individuals show up to their workdays and what they’re looking for out of their jobs can differ greatly by generation, said Amy Mosher Berry, CEO and founder of Visions Internships in Marlborough.

While there are comparatively far fewer individuals in the workforce from the Silent Generation, composed of those born 1928 and 1945, there are still many who serve in important roles, including on boards and committees, Mosher Berry said. Most of them are not grinding to earn an income, but are instead emphasizing their legacy in the places they can have a real impact.

This theme of legacy trickles down to the Baby Boomers, those born between 1946 and 1964. Mosher Berry sees these workers focusing on financially equipping themselves for retirement, with many having served decades at the jobs they’re in. As they set their sights on retirement, Boomers are looking to set up succession plans and prepare their businesses and organizations for their upcoming departures.

When it comes to Millennials and Gen Z, they’re not nearly as focused on company loyalty and staying with one company for the long term, said James Goldsberry, founder and CEO of NextUp2Lead, a Westborough-based managerial coaching firm.

“That loyalty goes more toward the technology, the purpose, the meaning of the work, not necessarily the company and corporation that they have,” said Goldsberry.

This sentiment is widely supported in literature analyzing the wants of younger generations in the workplace.

A 2025 global study performed by Deloitte of more than 23,000 Gen Zers and Millennials found 89% of Gen Z and 92% of Millennials highlighted a sense of purpose as important to their job satisfaction and well-being. Furthermore, 44% of Gen Zers and 43% of Millennials reported they had left a position due to lack of purpose, and about 40% of both had rejected to participate in assignments going against their personal beliefs or ethics.

This creates disconnect between generations, with older generations in leading roles not quite getting this social conscious mindset transition, said Mosher Berry.

“Employers are missing that for the most part. They're not grasping how important that is to young people,” she said.

For Gen X, this time of clashing is ripe with potential, said Valerie Zolezzi-Wyndham, CEO of equity-based leadership consulting firm Promoting Good in Worcester.

“Those of us in the middle have this really beautiful opportunity to be the bridge between those two other generations,” Zolezzi-Wyndham said. “That top generation is going to retire, and those organizations that have not invested in this new generation are going to be losing business, losing employees, losing everything.”

Shifting norms

Through her work assessing the differing experiences of those working within the same companies, Zolezzi-Wyndham has observed when it comes to cross-generational complaints, the common denominator is often the contrasting ways generations define their commitments to and boundaries for the work they do.

“One of the big challenges that exists that creates this conflict on intergenerational teams is that there isn't work done to set shared definitions and shared expectations, and so there's assumptions that are coming in from both sides that don’t go addressed,” she said.

Common tensions rise to the surface and circle the different ways generations prefer to communicate, she said. Whether it’s a preference for in-person vs. remote work, calls vs. texts, or boundaries around working hours, she sees employers and employees jump to conclusions about each other's preferences not always accurate.

These varying preferences are very apparent for Lexi Brissette, the 25-year-old vice president, commercial real estate specialist at NAI Glickman Kovago & Jacobs in Worcester.

While Brissette and other Gen Z professionals tend to much prefer texting for correspondence, the same is not true for NAI Glickman’s leading Baby Boomer partners.

“If I'm not in the office, they will wait, essentially, to have conversations until I get into the office. They don't like to just shoot me a text or a phone call as often,” she said.

Additionally, Brissette experiences her generation as restless to succeed and reap the financial benefits of that success than previous generations. As opposed to sticking with a company for years, if not an entire career, she sees an itching for more rapid fulfillment, potentially throwing older generations off.

This is one example of how the importance of workplace expectations, goals, and boundaries become so critical.

Younger people have made clear boundaries around their working hours and are not as willing to work outside of those set in their contracts, another cultural shift that can throw off those who have been in the workforce longer, said Zolezzi-Wyndham.

When not discussed clearly, these types of boundaries can be misinterpreted as a lack of commitment or laziness, but Zolezzi-Wyndham doesn’t think that’s the case at all.

“It's not because they're not committed. It's because they are approaching work with different values and different sets of expectations around what work should require for them,” she said.

Mutually-beneficial mentorship

As impenetrable as these clashes in penchants and conventions may be, these Central Massachusetts leaders see a clear path forward through mentorship and intentional, purpose-driven communication.

“Sometimes people feel like a mentorship needs to be this formal program, and that's not necessarily the case. In fact, I think when people hyperfocus on over formalizing a mentorship program, you can lose opportunities,” said Mosher Berry.

Instead, she suggests pairs meet up for coffee or have virtual coffee together.

She goes further to support mentorship outside of the confines of individual companies. She encourages her clients to reach out to professionals in their field of interest to speak about what their career path has been like, things they wish they had known when starting their career, and what they’ve learned.

“As long as you can nail down that busy professional, they're often quite honored to be in those conversations,” she said.

People, no matter their generation, are eager to collaborate, said Brissette. She sees mentorship as a mutually beneficial two-way street. She has co-workers who she supports through her technological skills while they share their institutional knowledge.

In order to curate an environment where this kind of mentorship and mutual support is encouraged, the groundwork of expectations addressing cross-generational concerns needs to be laid, said Zolezzi-Wyndham.

“The bottom line is that you need much better communication, and that communication has to be bi-directional; and it can't just be about leadership saying ‘This is the way it's going to be,’” she said.

She suggests leaders have conversations about workplace boundaries and needs, and leaders need to come into these communications willing to make changes. Or else, she said, they’re just breaching trust.

“Do not have the conversation unless you are willing to adjust your systems. Because if you invite people to share what they need in the workplace or what they want their boundaries to be, but you're not willing to make any changes, then all you're doing is breaking trust and frustrating people,” she said.

Workplace differences themselves are not an inherent problem, said Goldsberry, but when these differences are put into a dynamic that doesn’t encourage communication and honestly, it can prove a breeding ground for misunderstandings and tension.

“Identify and focus on some common touch points. You may have a hobby that's the same hobby as another generation, and that common touch point will help build the relationship,” said Goldsberry. “Use that as vehicles to bridge that age gap and style gap, and in that you can build some shared experiences.”

“Each generation has a gift to bring to the workforce. Every generation has a perspective on the world that is valuable, but they're only going to share them with each other if there's trust,” said Zolezzi-Wyndham.

Mica Kanner-Mascolo is a staff writer at Worcester Business Journal, who primarily covers the healthcare and diversity, equity, and inclusion industries.

0 Comments